In search of big tuskers in Tsavo National Park

Tsavo National Park in Kenya is probably on every wildlife enthusiast’s bucket list. Renowned for its stories of man-eating lions and admired for its elephants covered in red dust and the Critically Endangered hirola, a trip to Tsavo imbues the African wilderness with tranquillity and the prospect of observing big tuskers in their natural environment.

Spanning an area of 22,000km² – making it slightly bigger than South Africa’s Kruger – Tsavo is Kenya’s largest national park. And I had the good fortune to be guided in the park for nearly a week by Richard Moller, the Chief Executive Officer of The Tsavo Trust, and stay at Satao Camp in Tsavo East, which kindly subsidised some of the accommodation, meals and transfers.

The park’s nine big tuskers are among perhaps only 40 on the whole African continent today, as these so-called ‘hundred-pounders’ have been all but wiped out as a combined result of poaching, trophy hunting and large-scale exploitation of ivory for consumer goods. So it was a dream of mine to try to locate a few of these remaining iconic giants and capture them on camera for monitoring purposes and posterity.

Note from the editor: We are acutely aware of public sensitivity to disclosing the locations of large tuskers. This feature was put together under the close supervision of the Tsavo Trust, which takes excellent care of Tsavo’s special giants. Read on for further information.

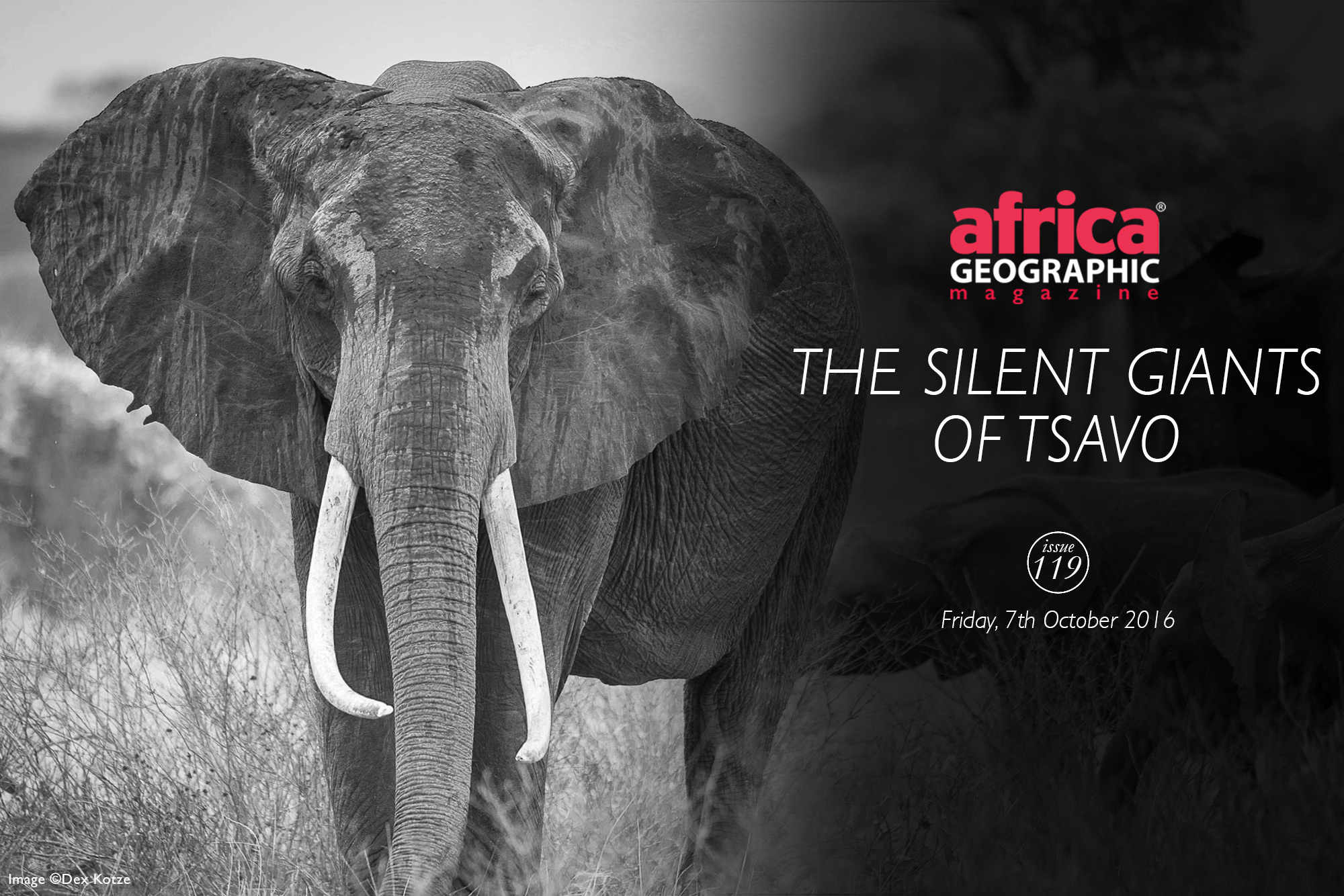

? A herd of elephants in Tsavo National Park © Dex Kotze

The search for Tsavo’s tuskers

Africa Geographic arranged my Tsavo safari after I expressed a wish to see some of the last remaining huge elephants.

Arriving in Kenya for research and a photographic safari excursion means that you need to pack very few clothes and ensure your photographic equipment takes precedence. It is only by patiently spending 10 to 12 hours a day in the bush that you will have even the remote chance of seeing a big tusker.

Richard is a seasoned fixed-wing pilot and treated me to the joys of aerial observation aboard his Super Cub during his daily reconnaissance flights. It struck me how easily Richard could identify the elephants from a great distance, and we circled far away from them to avoid disturbing their peace.

Thanks to his skill, I achieved my goal and saw three of the largest bulls in the park, along with a few huge females and several emerging tuskers. One evening, after spending 12 hours in the wilderness, local Tusker beer in hand by the fireplace, Richard and I reminisced about the wonders of nature that we had managed to locate during the day. While the waterhole at Satao Camp was inundated with elephants, sometimes as many as 60 quenching their thirst until late at night, our conversation focused on how to save these hidden icons of Africa’s savannahs. No sooner would a herd step back into the darkness to wander miles away in search of food than another 30 elephants would arrive, rumbling and friendly-scuffling in the dark, splashing at the waterhole in sheer delight at the coolness on their bodies. It was a remarkable experience to fall asleep in our luxury tents later, surrounded by the night’s stillness, only interrupted by the sounds of these majestic beings.

Elephant populations in East Africa

Sadly, the egoic obsessions of Western hunters to kill powerful beings is still very prevalent in this day and age. Although Kenya has banned hunting since the mid-70s, elephants still roam freely into neighbouring Tanzania, where hunting is still legal. Consequently, some iconic elephants have wandered perilously across the open borders, only to risk being shot and mounted on a mantelpiece 14,000km away.

Observing these magnificent elephants in Tsavo East left me in turmoil. Years of my research have revealed how world leaders, CITES, and corruption across the range, transit, and consumer states have mostly failed these majestic and sentient beings. Where once 10 million elephants roamed the African continent, some 200 years ago, less than 420,000 now remain.

While travelling from Satao Elerai Camp in Amboseli, I witnessed how Tsavo East and West are bisected by the road that runs from Nairobi to Mombasa. China has also financed over 90% of the new 609km railway line that runs parallel to the road and is due for completion in December 2016. The Mombasa-Nairobi standard-gauge railway is Kenya’s largest infrastructure project since the country’s independence. It will eventually link Mombasa, which is the world’s most significant transit point for ivory smuggling, with other major East African cities, such as Kampala in Uganda. The railway line is designed to carry 22 million tonnes of cargo a year, or a projected 40% of Mombasa Port throughput by 2035.

In this video by Richard Moller, you can watch some of Tsavo’s elephants dealing with their new environment:

Upon seeing this massive railway project, I recalled how, upon arriving in Nairobi from Johannesburg days earlier, my attention was immediately drawn to the fact that nearly 90% of travellers at passport control were Chinese, including those in the queue for Kenyan passport holders. I had a brief flash of Howard French’s book, China’s Second Continent: A guide to the new colonisation of Africa, that I had read a year ago. I witnessed his experience firsthand and shuddered to think of the aftermath for Africa’s wildlife, considering the vast numbers of elephants poached to fulfil the Asian demand for ivory.

The Great Elephant Census is the largest pan-African aerial survey since the 1970s, and recently released its results ahead of the CITES Conference of the Parties in Johannesburg at the end of September 2016. It showed that, between 2007 and 2014, the number of savannah elephants plummeted by at least 30%.

At this year’s Conference of the Parties, a vital decision was made concerning the deplorable practice of ivory sales for carvings and collectors’ cabinets. Members rejected Namibia and Zimbabwe’s proposals, strongly supported by South Africa, to export their ivory stockpiles. After all, the morally unjustified decision in 2008 to allow a one-off sale of 106 tonnes of ivory to Japan and China yielded a mere US$15.5 million, which is an absolute pittance if one considers how 35,000 elephants a year have been slaughtered for their ivory since that time, only eight years ago.

However, another proposal by the African Elephant Coalition, comprising 30 African states, to up-list Southern African elephants to Appendix I for the highest possible protection, was sadly rejected at the CITES conference after the EU blocked it. Importantly, Botswana, with nearly one-third of the continent’s elephant populations, supported the coalition proposal.

Collaboration efforts

On the second day of my trip, we spotted a carcass of an elephant that had died a natural death. Later in the day, Richard asked the KWS rangers to accompany him to collect the ivory lying next to the dead animal. Their conversation was in fluent Swahili, and it was clear that their relationship with the rangers was marked by deep mutual respect for each other’s work and their efforts as custodians of Tsavo’s heritage.

Two years ago, the carcass of Satao, the world-famous big tusker, was found in the area. He had been killed by a poisoned arrow and found with his face hacked to pieces for his tusks, which were destined to decorate the desk of an Asian collector. World conservationists called this a monumental loss. Given the prevalence of poaching, Richard would like to see one or two of the iconic Tsavo tuskers granted a Presidential Security Decree to protect them, as was the case with the famous tusker called Ahmed in Kenya’s Marsabit National Park in the early 1970s. If successfully repeated, this will be a momentous achievement in conservation leadership by an African president.

Over the next few days, I was elated to observe the successful cooperation between The Tsavo Trust, a field-based NGO established four years ago, and the Kenya Wildlife Service. In less than four years since Richard Moller embarked on his NGO’s programme to protect Tsavo’s tuskers, elephant poaching in Tsavo has reduced by over half. There are few examples of close co-operation by African NGOs and their government counterparts in wildlife conservation, so this is a notable venture. Richard and his co-pilot, Josh Outram, spend over 60 hours per month recording the silent giants of Tsavo’s savannahs, and they have donated more than US$300,000 worth of anti-poaching vehicles and equipment to KWS since its inception.

They also work closely with local communities, fully recognising that the survival of Africa’s iconic species depends on the participation of people who live along park borders. Human-wildlife conflict is at the root of an ecological disaster still in its infancy, and apex predators such as lions are especially affected in East Africa, as they pose an enormous threat to the cattle herders and are consequently often killed or poisoned.

The ubiquitous pastoralists, according to my sources, spend months in the park grazing the cattle of wealthy politicians, even though it is illegal. Over the course of our week in the area, Richard and I flew over several cattle herds, and a few days later, on my outward journey from Tsavo East, I again saw several thousand cattle and goats within the park boundaries. The implications for Tsavo’s ecosystem are immense. From the Super Cub, I noticed that areas north of the Galana River were devoid of flora and saw massive expanses of soil erosion caused by livestock hooves driven to the river for water.

According to United Nations documents, Kenya’s current population of 46 million is projected to swell to 157 million by 2100. Africa’s people will swell from 1.2 billion today to 4.4 billion by the end of the century. These existing difficulties will increase tenfold over the next 80 years. Unless addressed now by closely involving local communities in conservation initiatives, this increase will spell disaster for Africa’s endangered species.

Where to stay in Tsavo

If you’re planning a trip to Tsavo National Park, Satao Camp in Tsavo East is a luxury eco-camp that makes an ideal base for exploring the area. Thanks to its fabulous light and unbelievable views, Tsavo East is a paradise for photographers who particularly wish to capture the Mudanda Rock, Lugard Falls, and the Yatta Plateau. With only one lodge and four camps in Tsavo East, the park’s rolling hills have a remote feel, making Satao Camp feel rather exclusive.

Nestled amongst trees, the semi-circular layout around a waterhole of its 20 ensuite tents offers guests fantastic views from their private verandahs – on which they can toast a Tusker after spending the day in search of this beer’s namesake.

About the author

Dex Kotze is a businessman who brings 30 years of business experience to conservation. With a deep passion for Africa’s wildlife and wildlife photography, he founded an NGO, Youth 4 African Wildlife, to create next-generation global ambassadors for endangered African wildlife through experiential research, social media, film, and photography. Since its inception four years ago, over ZAR800,000 has been raised for rhino conservation, with proceeds assisting in the successful translocation of rhinos to Botswana and the purchase of anti-poaching security dogs and equipment. His passion also led him, in 2014, to serve as a core strategist for the international NGO Global March for Elephants, Rhinos and Lions, raising international awareness of the plight of elephants, rhinos, and lions.

Dex Kotze is a businessman who brings 30 years of business experience to conservation. With a deep passion for Africa’s wildlife and wildlife photography, he founded an NGO, Youth 4 African Wildlife, to create next-generation global ambassadors for endangered African wildlife through experiential research, social media, film, and photography. Since its inception four years ago, over ZAR800,000 has been raised for rhino conservation, with proceeds assisting in the successful translocation of rhinos to Botswana and the purchase of anti-poaching security dogs and equipment. His passion also led him, in 2014, to serve as a core strategist for the international NGO Global March for Elephants, Rhinos and Lions, raising international awareness of the plight of elephants, rhinos, and lions.

Dex is also a director of The Rhino Orphanage in South Africa, a non-profit company based in Limpopo. This was the first of its kind when it was established in 2012, and it is a haven where injured and orphaned rhino calves are cared for, with the aim of returning them to the wild.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()