Africa’s undiscovered paradise

São Tomé and Príncipe are amongst Africa’s best-kept tourism secrets – two bijou volcanic islands off the west coast of the continent, brimming with ecological marvels, stunning biodiversity, captivating history, and warm, welcoming inhabitants. Imagine an island paradise where azure waters lap at the shores of deserted beaches beneath waving palm fronds. A land where thick rainforests filled with Galápagos-like evolutionary wonders tumble their way down volcanic precipices to the rocky coastline below, and the jungle has reclaimed the once widespread colonial plantations. It is a place where time has, by all appearances, stood still.

São Tomé and Príncipe

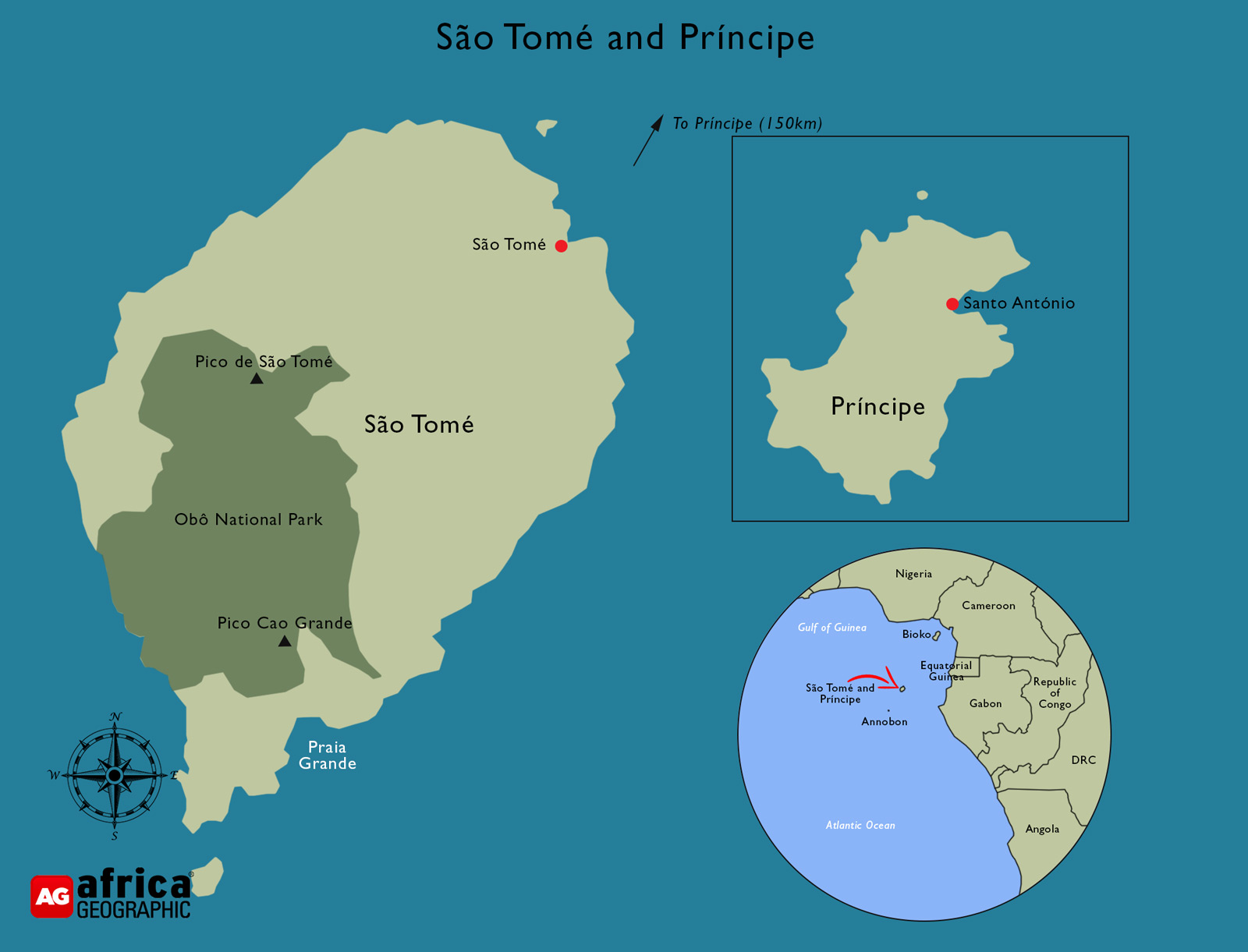

The two jungle-choked islands are about 140km apart, over 200km off the coast of Gabon in the Atlantic Ocean in the Gulf of Guinea. Together, they are Africa’s second smallest country (both in terms of population and size) after Seychelles. Along with the neighbouring islands of Bioko and Annobón, São Tomé and Príncipe owe their existence to volcanic activity as shifting tectonics formed the Cameroon Line of volcanoes and forced part of the seabed upwards over 30 million years ago. The resultant topography is dramatic. This is no land of gentle, undulating hills – instead, sharp peaks dominate the skyline, and streams radiate down the mountains into the plunging valleys below.

The resultant rich volcanic soils, equatorial climate, and monsoon rainfall levels set the stage for a staggeringly diverse range of plant life. Verdant forests cover most of the islands, ranging from lowland forests around the coastlines to the mysterious cloud forests 1,400 metres and more above sea level. As the two islands have always been separate from the African continent, endemism is high with many plant and wildlife species found nowhere else on earth. Though the islands are small, naturalists exploring São Tomé and Príncipe receive a backstage pass to evolution’s theatre – hence the islands are sometimes referred to as Africa’s answer to the Galápagos (which may, in fact, be underestimating their biodiversity importance).

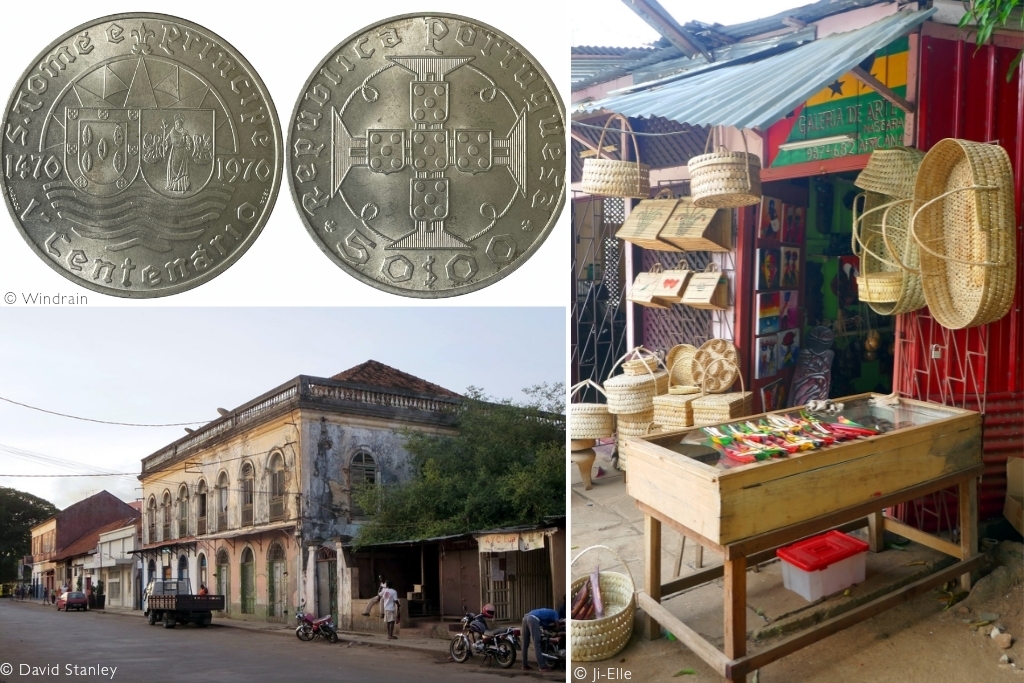

São Tomé and Príncipe were (by all accounts) uninhabited by people before the arrival of Portuguese explorers in the 15th century. As the islands were gradually colonised and settled, their convenient position created an important stop-over point. The islands, particularly larger São Tomé, rapidly evolved into a major commercial and trade centre for the Atlantic slave trade. At the same time, the bountiful soils and wet climate (and the availability of free, forced labour) made the islands ideal for agriculture – predominantly sugar cane. As competition from other global sugar markets grew, the islands’ farming activities gradually transitioned to coffee and cacao, eventually becoming the world’s largest cocoa producer at the turn of the 20th century. With independence in 1975, the plantations were nationalised. Many fell into a state of disrepair and were abandoned, leaving behind a snapshot of history frozen in time. (Read on for more on these plantations – termed roças.)

São Tomé

At 859km², around 50km long and 30km wide, São Tomé is the larger of the two islands and the more populous by far (though everything is, of course, relative). The delightfully decrepit capital of the eponymously named São Tomé city lies in the island’s north-eastern corner: colourful, vibrant, and bearing Portugal’s colonial thumbprint. Here visitors can visit the tiny, cream-coloured 16th-century fort of São Sebastiãn and accompanying museum or the Nossa Senhora da Graça (“Our Lady of Grace” – one of the oldest cathedrals in sub-Saharan Africa) to soak in the region’s history. Alternatively, a trip through the streets past lively vendors will offer the chance to enjoy some local cuisine (fish, perhaps, with some breadfruit and cooked banana – a staple dish). The markets present the opportunity to purchase crafts and meet the local São Toméans/ Santomeans (or even spot the president wandering by in flip flops).

Away from the city, much of São Tomé is protected by the Obô National Park, which extends to include much of Príncipe as well. In the central part of the park lies one of São Tomé’s most famous landmarks: Pico Cão Grande or the “Great Canine/Great Dog Peak”. This bizarre topographical feature stands out for miles – a tooth-like volcanic plug that rises over 370 metres above the surrounding terrain. Pico Cão Grande is the most dramatic of the many volcanic plugs, necks and outcrops on both islands, composed of a rare type of extrusive volcanic rock known as phonolite. Due to the slippery moss-covered vertical cliff faces, unpredictable fogs and unexpected deluges, few have successfully navigated the climb to the top of Pico Cão Grande.

This section of Obô National Park is also home to Pico de São Tomé, the country’s highest peak at 2,024 metres above sea level. The upper slopes are covered in primary forest, the trees swathed in decorative layers of lichen and sporting a multitude of different orchids and other epiphytic species. Unlike Pico Cão Grande, summiting Pico de São Tomé can be attempted by hikers, though a sturdy pair of boots is essential.

Príncipe

Around 140 km north-east of São Tomé (a 30-minute flight away) lies the remote wonderland of Príncipe. The tiny island covers an area of 136km², including the surrounding forest-clad islets. The population numbers just under 7,000 people, most of whom reside in Santo António (the only town). In today’s world, Príncipe is the closest thing to an untouched paradise any traveller could ever hope to explore.

The entire island has been designated the UNESCO Island of Príncipe Biosphere Reserve, and the lush forests are crisscrossed by weaving trails leading to picturesque waterfalls. These verdant surroundings (together with São Tomé) are home to more endemic species per square kilometre than anywhere else on earth. Along the edges of the island and islets are the kind of beaches that are almost too perfect to be true – deserted, fringed by palms providing ample shade and warm azure waves lapping at the sand. Many of the lodges in the area sport a private beach, complete with snorkelling and canoe activities (and the odd beach bar).

The “Lost World” atmosphere of Príncipe is only accentuated by the “abandoned” plantations. Historically, these roças (also found on São Tomé) were self-contained, self-sufficient worlds ruled over by colonial households. The more extensive estates would have employed over a thousand people who lived within the roça “villages” with their own churches and hospitals. Today, most colonial mansions have been closed off or converted to luxury accommodation. However, local people still live in many of the roça villages, leading an almost entirely subsistence-based lifestyle. As the vegetation slowly reclaims the crumbling infrastructure, the result is a poignant insight into time gone past.

Astonishingly, Príncipe once found itself at the cutting edge of physics research when Arthur Eddington set out for a perfect position to observe the effects of gravity on light during a solar eclipse. This he found at Roça Sundy when he observed that the light from stars was bent by the sun’s gravity, confirming a significant aspect of Albert Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity.

Evolutionary islands

Since Darwin’s initial forays into the natural wonders of the Galapagos Islands, biologists have seen islands as evolutionary goldmines. The idea is that the smallest and most isolated islands will demonstrate the most dramatic examples of adaptation. São Tomé and Príncipe, having never been part of the mainland, are the perfect example of this principle in action – the endemism levels of these tiny islands are simply astonishing. To this day, new species of both fauna and flora are regularly discovered, many endemic to either one or the other island. The mammal contingent is almost entirely represented by bats and one terrestrial mammal: the São Tomé shrew.

The beaches are popular nest sites for four different species of endangered turtles. Female olive ridley, green, hawksbill and leatherback turtles begin to arrive in November to nest, and the hatchlings launch their perilous journey back to the ocean in March.

Of particular interest to biologists are the seven amphibian species. Amphibians are intolerant of saltwater, so how the six frog species and the worm-like “cobra boba” (Schistometopum thomense) found their way there is a matter for considerable debate…

Birds of a different feather

Like Darwin’s finches, the birds of São Tomé and Príncipe are intriguing. It is almost impossible to give a precise number of endemics on offer, simply because different sources recognise diverse species/sub-species distinctions, and research continues. Whatever the total, it is clear that the birding on offer in São Tomé and Príncipe is extraordinary, and enthusiasts are guaranteed to tick off several species found nowhere else. Only in São Tomé and Príncipe can birders experience the thrill of standing in the gloom of the forest and looking up to see the incongruous shape of a tropicbird against the leafy backdrop of the canopy.

One aspect that makes the birdlife even more fascinating is the high levels of dwarfism and gigantism. This is a pattern seen in islands worldwide, where species of small families evolve to be bigger (likely in the absence of competition) and big species get smaller (perhaps due to lack of available space). Thus, the São Tomé and Príncipe birds include the giant weaver and giant sunbird (the world’s largest members of the two families). The mysterious São Tomé Grosbeak is the largest member of the canary family and was only rediscovered in 1991 after a century’s absence. On the opposite side of the spectrum is the critically endangered dwarf olive ibis. On the isolated island, the São Tomé oriole has lost much of its yellow pigmentation, providing vital clues about the role of colour and competition in birds.

A typical checklist of some of the birding specials on display would include the Dohrn’s thrush-babbler, São Tomé short-tail, several species of white-eyes, the São Tomé prinia, São Tomé fiscal shrike, maroon pigeon, Príncipe thrush, São Tomé lemon dove, São Tomé olive pigeon, Príncipe kingfisher, Príncipe glossy starling, Príncipe sunbird, velvet-mantled drongo and adorable São Tomé scops owl. Timneh parrots soar past in small but noisy flocks, and some of the marine birds include white-tailed tropicbirds, sooty terns and brown and black noddies.

Explore and stay

Want to go on safari to São Tomé and Príncipe? To find lodges, search for our ready-made packages or get in touch with our travel team to arrange your safari, scroll down to after this story.

A popular phrase amongst the locals of São Tomé and Príncipe is “leve leve” – the Santomean equivalent of “easy does it”. It perfectly encompasses the laidback atmosphere of this down-to-earth country where life moves at a simpler, more human pace. Yet for all that, the two islands offer the perfect escape from worldly stresses, the plethora of activities on offer do not allow for a dull moment. From exploring underwater caves and snorkelling past bright fishes to hiking along forgotten paths in thick forests in search of feathered treasures, the purity of São Tomé and Príncipe’s natural world cannot fail to delight.

The two rainy seasons run from September to November and March until June, but the country receives high levels of rain all year round. The weather has to be taken with the same “leve leve” approach as the rest of the island. Though the risk is slight in the more remote parts of the islands, it is important to take malaria precautions. There are budget “pensão” accommodation options in the larger cities and villages, but it is at the more upmarket lodges that the true magic of the islands can be fully embraced.

For those looking to indulge their inner Epicurean, the culinary delights are never-ending. Visitors can sample what is arguably the best chocolate in the world – dark, rich and pure and made onsite at the cacao plantations. At the world-famous Claudio Corallo Cacao and Coffee, chocolate-lovers can spoil their tastebuds with any combination of 80% dark chocolate and candied ginger/orange, salt or locally-sourced pepper.

With islands as isolated as they are, the ingredients for more substantial meals are almost all sourced from the land and combined in unusual and delectable ways. The fire and passion of Portuguese cooking are given their own local twist, creating a food experience that is both authentic and deeply flavoursome.

This mixed bag of cultural influences, fascinating and friendly local inhabitants, and the evocative history completes the sensory extravaganza that epitomises the São Tomé and Príncipe experience.

WATCH: I AM FROM PRÍNCIPE (3:41)

WATCH: I AM FROM PRÍNCIPE (3:41)

Resources

Fundação Príncipe is committed to the sustainable development of tourism on the islands of São Tomé and Príncipe. Learn about them in our private travel and conservation club – and please consider a DONATION to support their work (donating via our club is safe).

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()