Private landowners in South Africa now collectively support the largest population of white rhinos on the African continent. More than half of the continent’s rhinos are in private hands. This was the inevitable outcome of declining wild populations and increasing numbers of rhino found on private land. It brings into stark relief the importance of the private sector in rhino conservation. Given the rising costs associated with protecting rhinos, what will it take to build resilience in the private industry?

Private landowners in South Africa now collectively support the largest population of white rhinos on the African continent. More than half of the continent’s rhinos are in private hands. This was the inevitable outcome of declining wild populations and increasing numbers of rhino found on private land. It brings into stark relief the importance of the private sector in rhino conservation. Given the rising costs associated with protecting rhinos, what will it take to build resilience in the private industry?

A new study published in Frontiers examines the contribution of private and communal land to rhino conservation as well as the financial and policy implications of such an arrangement. The authors also outline the policies necessary to create a secure environment for private conservation, including decision-making around trade, hunting and management.

Private contributions to rhino

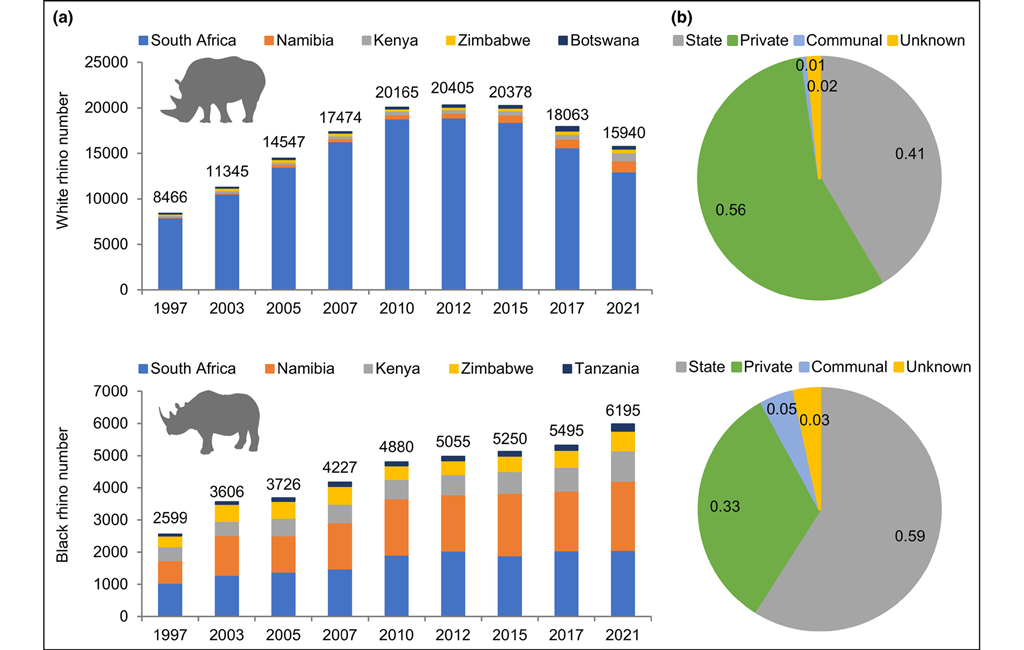

Across the continent, over half of Africa’s white and a third of its black rhino occurred on private land in 2021. An additional 5% of the continent’s black rhino were held on communal land in Namibia and South Africa.

Despite having suffered considerable poaching losses, South Africa remains home to the largest number of white rhino (81%) on the continent, as well as around a third of the remaining black rhino. However, the focus of poaching on state-run parks such as the Kruger National Park and Hluhluwe-Imfolozi Park has resulted in a steady decline in wild rhino on state land. At the same time, the number of rhinos on private land has increased. Consequently, the proportion of the country’s white rhinos on private land has shifted from 25% in 2010 to 53% in 2021.

Data from other rhino range states, such as Zimbabwe and Namibia, also indicates a similar trend. Private lands in Zimbabwe now hold 88% and 76% of the country’s black and white rhino, respectively. 75% of Namibia’s white rhinos are found on private land, while 27% of its black rhinos are on private land, and 7% are in community conservancies.

Costs and incentives

Previous research showed that, on average, private properties spent approximately US$2,200 per animal on security in 2017, amounting to a cost of over US$100,000 per property on average for that year. More recently, this security cost increased substantially – some 50% in only three years. International trade in rhino horn is banned, and the price of live white rhinos sold at auction has declined 75% over the last decade. Furthermore, private and communal landowners receive no direct state funding to support their enterprise or the cost of securing their animals. Consequently, private ownership of rhinos (or land hosting them) has become considerably less attractive.

Without any constitutional mandate to protect these rhinos, some landowners are simply disinvesting. This is not yet a significant trend for private custodians (some are even growing their herds and investing in more rhino), but this may be due to the hope that trade in rhino horn will eventually be legalised. If this reality does not materialise, large-scale disinvestment seems likely.

Furthermore, keeping intensively managed populations (fed and kept at higher-than-natural densities) may prove the more practical (financially and otherwise) strategy in keeping captive rhinos safe. These kinds of captive populations cannot maintain natural breeding or evolutionary processes and do not contribute to ecosystem function.

A new path for rhino?

Future policies must identify ways to incentivise private rhino ownership to compensate for rising security costs. The authors acknowledge that the trade in rhino horn could theoretically provide such an incentive. However, they emphasise the need for context-specific research that takes into account the complexities of the issues at play. They also indicate that trophy hunting is a crucial revenue source in funding protection, which could be hampered by the growing international pressure to ban trophy hunting. In terms of both trade and hunting, the researchers highlight the need for consideration of local contexts.

Given the potential for increasing emphasis on intensive farming systems, there also needs to be additional incentives for extensive systems where the captive animals lead more natural lives. These might include implementing a more favourable tax structure or eligibility for carbon credits or “rhino bonds”. Crowdfunded donations linked to conservation performance are also a possibility.

“If additional incentives are not enabled, we risk losing private and communal rhino custodians, and with them, half of the remaining African rhinos”, concludes lead author Dr Hayley Clements.

In February 2023, the owner of the world’s largest private rhino farm, John Hume, announced that his Platinum Rhino farm, home to close to 2,000 rhino, would be auctioned in April. His press release cited rising security costs as the reason for the sale.

Reference

Clements, H. S., Balfour, D. and Di Minin, E. (2023) “Importance of Private and Communal Lands to Sustainable Conservation of Africa’s Rhinoceroses,” Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, (20230109)

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()