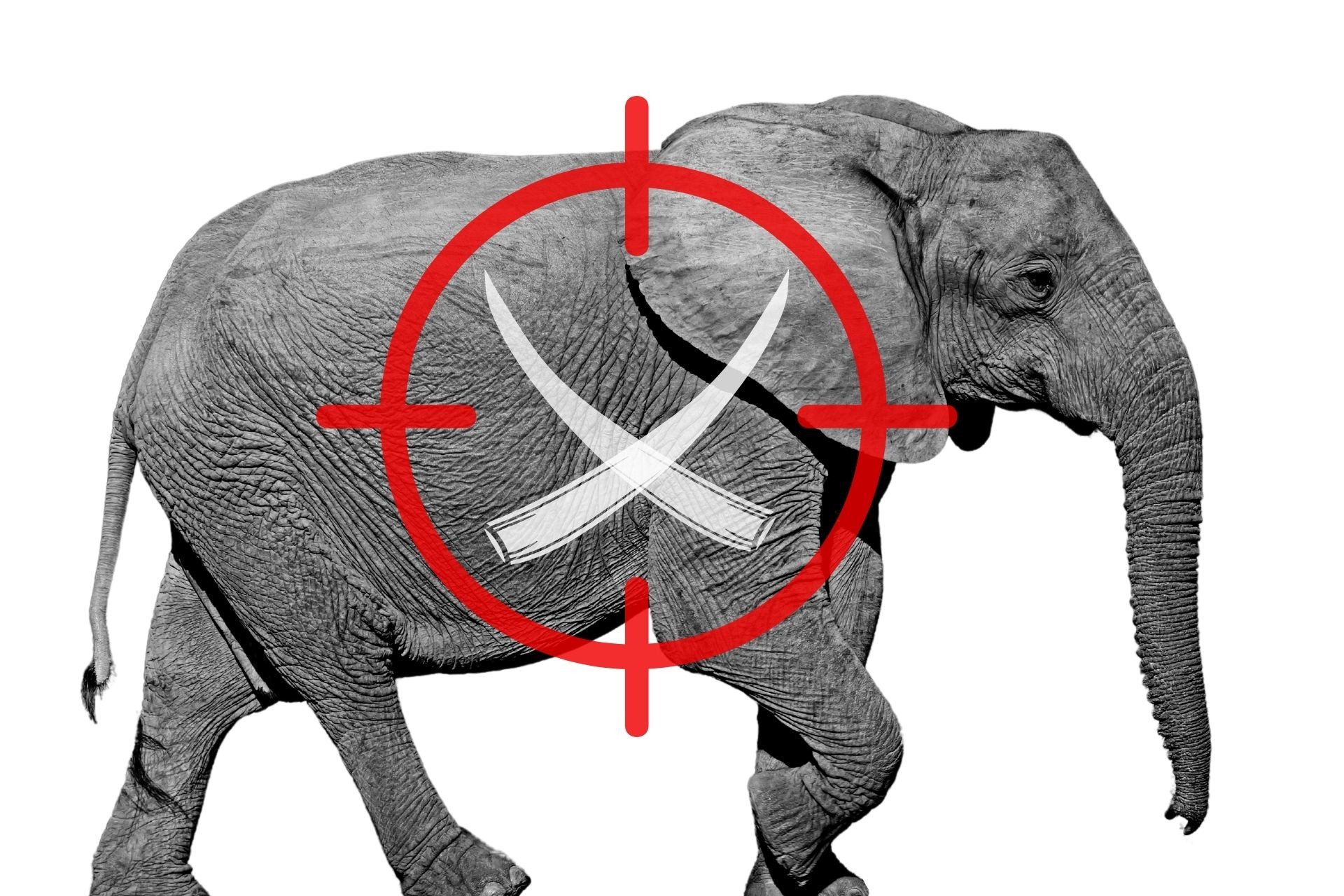

Research has confirmed what many experts have been suggesting for decades: ivory poaching selectively drives the evolution of tuskless elephants. The new study, published in Science, methodically demonstrates the devastating effects of poaching on the elephants in Gorongosa National Park in Mozambique. In essence, the article confirms that elephants had been “genetically engineered” to be born without tusks.

During the Mozambican Civil War from 1977 to 1992, the elephants of Gorongosa National Park and the rest of the country were indiscriminately poached. Ivory sales were used to fund weapons for armed forces on both sides, and the wholesale slaughter resulted in the loss of around 90% of the region’s elephants. Tuskless individuals (of no interest to ivory poachers) were more likely to survive and began to pass their genes on to their offspring as the park stabilised.

Intensive poaching in Africa has long been associated with increasing numbers of tuskless elephants. However, prior to this paper, no research had quantified the phenomenon, and the exact mechanisms behind the tuskless characteristic had not been investigated.

Researchers compared historical video footage and contemporary records to demonstrate that the frequency of tuskless females in Gorongosa increased nearly threefold from 18.5% to 50.9% over 28 years. To test whether or not this was due to a chance event and a population bottleneck, they used a simulation based on the assumption that tusked and tuskless females were equally likely to survive. The outcome of the simulation concluded that this was extremely unlikely to have occurred due to chance. Instead, the authors calculated that the survival chances of tuskless females were five times those of tusked females during the war.

Tuskless elephants are found in most (if not all) savanna elephant populations, always in small proportions under natural conditions and, importantly, almost always in females. So, the next step for the researchers was to examine the genetic basis of the trait and the effect of selection on future generations. The proportion of tuskless elephants in Gorongosa (a total population of around 700) has remained significantly elevated long after the war. This shows that the trait is clearly heritable and an evolutionary response to poaching-induced selection.

Further investigation revealed that the gene for tuskless elephants is likely dominant, sex-linked (on the X chromosome) and male-lethal. Simply translated, this means that the mother will pass the gene to some, if not all, of her daughters, and it will be expressed in their phenotype (physical appearance). The fact that it is male-lethal means that male zygotes that inherit an X-chromosome with the gene will not be viable and will not develop to term. Consequently, the long-term prevalence of the tuskless gene could potentially skew the sex ratio of an elephant population.

The genetics are complicated slightly because some of the females express a mid-way phenotype, with only one tusk. It would be overly simple to expect that a complex trait like tusk growth to be controlled only by the complete dominance of one gene. It is highly likely that genes on other chromosomes also have an effect. The researchers believe that they have identified at least one X-linked gene (AMELX) and one autosomal gene (MEP1a) behind the genetic selection in Gorongosa, but further research is needed. They also point out that there are some anecdotal reports of tuskless male savanna elephants. While this is likely due to injury or observer error, they cannot rule out alternative genetic mechanisms that may play a role.

Every organism alive today has at least partly evolved due to “standing genetic variation”, where some individuals in a population possess a different type of gene that confers a distinct physical trait. Under certain environmental conditions, this characteristic may be disadvantageous (as in the case of tuskless elephants in protected areas), but a change in circumstances may come to favour the alternative form. In this case, rampant poaching has driven the selection of the tuskless genotype in the space of a generation.

The authors conclude that their research “shows how a sudden pulse of civil unrest can cause abrupt and persistent evolutionary shifts in long-lived animals even amid extreme population decline”. Though tuskless elephants can survive and thrive without them, tusks are multipurpose tools used in ways that shape the environment around them. A massive increase in the number of tuskless elephants could have substantial and unforeseen impacts on local ecosystems. Fortunately, the researchers believe that if Gorongosa National Park continues its phenomenal recovery, this process will abate.

Resources

The full paper can be accessed here: “Ivory poaching and the rapid evolution of tusklessness in African elephants”, Campbell-Staton, S., et al. (2021), Science

For more about the recovery of Gorongosa: The Restoration of Gorongosa National Park

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()