Kenya's resilient (almost secret) wilderness

“Wildlife is something which man cannot construct. Once it is gone, it is gone forever. Man can rebuild a pyramid, but he can’t rebuild ecology, or a giraffe” ~ Joy Adamson

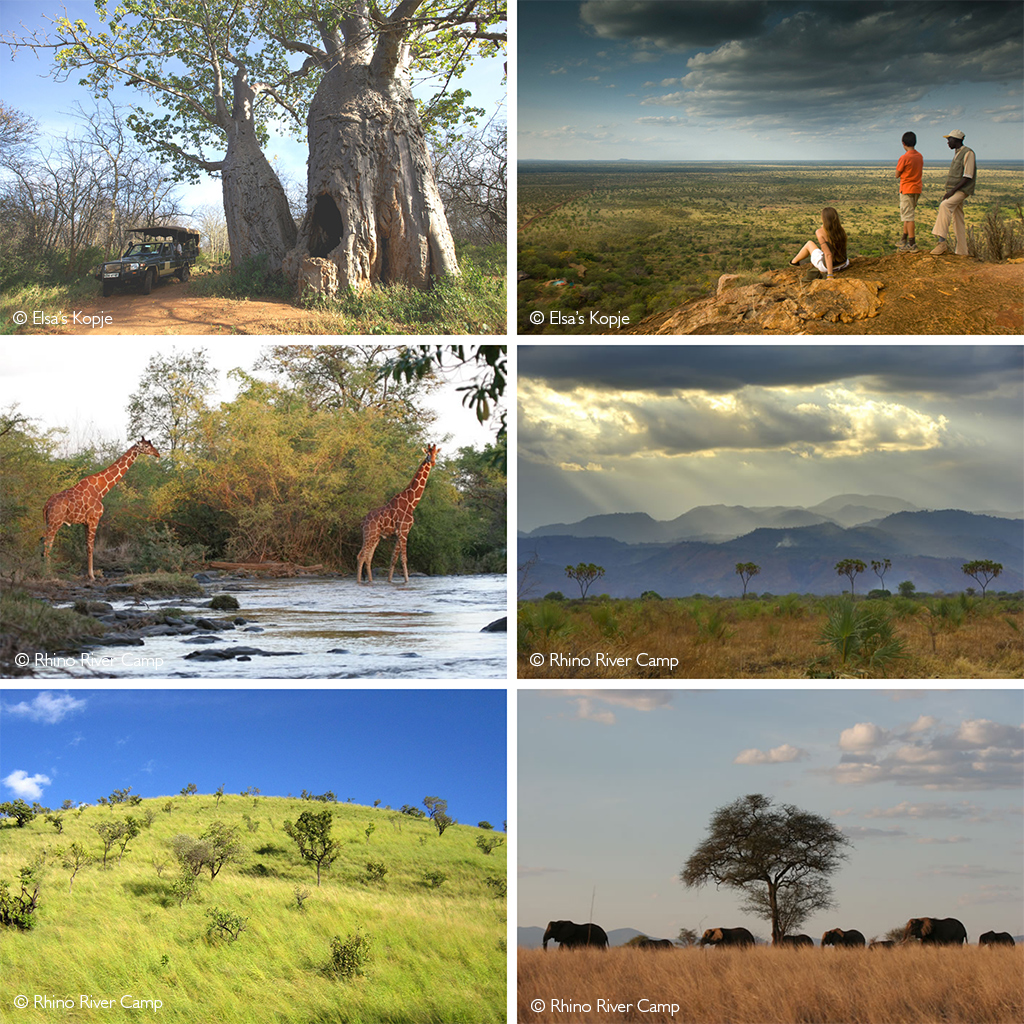

With unearthly stands of gaunt doum palms, sprawling grasslands, twisting riverine forests, and swamps populated by abundant wildlife, Meru National Park is perhaps Kenya’s best-kept (or maybe forgotten) safari secret. Exploring this national park is less about ticking off a checklist or rushing to the next sighting, and more about marvelling at the scale of this unspoilt wilderness free from the crowds of the more popular Kenyan safari circuits.

There is no doubt that had Joy Adamson still been alive today to witness the miraculous recovery of Meru National Park, she would have been delighted. Today, the park has been restored to its former glory – a magnificent chunk of wilderness central to one of Kenya’s largest protected areas.

Meru National Park and the Meru Conservation Area

Meru National Park occupies 870km² (870,000 hectares) of central Kenya, some 300km from the capital city Nairobi and offering views of snow-capped Mount Kenya on the distant western horizon. The park forms a vital part of the much larger Meru Conservation Area, which centres around the Tana River system and protects nearly 5,000km² (five million hectares). It covers habitats that range from lush green vegetation on rich volcanic soils to semi-arid scrublands and open plains. In addition to the Meru National Park, the complex of protected areas includes Bisanadi, Rahole and Mwingi (formerly Kitui North) National Reserves and the massive Kora National Park. The result is one of Kenya’s most extensive protected spaces, second only to the Tsavo ecosystem in size.

| Meru National Park | 807km2 (87,000 hectares) |

| Kora National Park | 1,787km2 (178,700 hectares) |

| Bisanadi National Reserve | 606km2 (60,600 hectares) |

| Mwingi National Reserve | 745 km2 (74,500 hectares) |

| Rahole National Reserve | 870km2 (87,000 hectares) |

The Tana River that marks Meru National Park’s southern boundary is Kenya’s longest river, flowing from the Aberdare Mountain Range and fed by springs from Mount Kenya, before winding a sinuous path to the Indian Ocean. The many permanent rivers that flow through Meru, including the major Rojerwero and Ura Rivers, are part of the Tana River basin and define the landscape of the park. These waterways are fed by springs on the Nyambeni Mountains and flow in parallel, creating the impression that the park is made up of a series of islands. Beneath a thick fringe of riverine forest, hippos and crocodiles lurk in the dark waters.

The wilderness that inspired Born Free

Like many of Africa’s protected areas, Meru’s story is one of triumphs and tragedies. The park gained international renown during the 1960s when the adventures of George and Joy Adamson and their hand-raised lioness Elsa made first literary and then cinematic history. The Adamsons raised Elsa from a cub, and Joy documented their experiences in a series of novels, the Born Free series. Elsa was eventually released into Meru National Park to live wild, and her final resting place is marked by a small gravesite on the park’s southern boundary. The park’s popularity skyrocketed when the eponymous film was produced, and visitors flocked to explore the famous setting.

Tragedy struck during the 1980s as poaching and unrest tore through much of Kenya. Both Joy and George were murdered in separate incidents, and the region’s wildlife was decimated. The park fell into disrepair, and the flood of tourists slowed to a trickle before drying up almost entirely. Hope came some 20 years later when concerted conservation work by the Kenyan Wildlife Service, the French Development Agency and the International Fund for Animal Welfare set in motion the painstaking process of returning the park to its former glory. The infrastructure was repaired with a substantial cash donation, and security and anti-poaching measures were put in place.

For the birds, and the Big 5

Today, the park is one of the country’s best maintained, but, more importantly, the wildlife and ecosystem have bounced back. Relocations of various species bolstered remaining populations, and Big 5 sightings are increasingly common (though not guaranteed). Elephant numbers have grown from fewer than 210 at the height of the poaching to over 670 at present. The region is also considered a Lion Conservation Unit by the IUCN. Though the long grasses in some areas can make predator spotting challenging, lions, cheetahs, and leopards are all present in healthy numbers, and encounters are even more special because they are seldom shared with anyone else.

The park’s reintroduced rhinos – black and white – are restricted to a smaller, fenced sanctuary where they can be best protected. However, this does little to detract from the wildness of the experience – the 84km² (8,400 hectares) enclosure section is perfectly sized to ensure that eager tourists have to work for their sightings!

Iconic animals aside, the many varied habitats of Meru are made all the more unique by the disparate rainfall levels across the park. This ensures a spectacular variety of fauna and flora, from moist savanna to the more arid specialists. Large herds of buffalos, impalas and zebras trudge through the swamps and feed alongside the rivers, and the sharp whistles of alarmed Bohor reedbucks hint at their presence in the reeds. The stark geometric patterns of reticulated giraffes tower over the woodlands. Lesser kudus, gerenuks, common beisa oryx, Grévy’s zebras and Somali ostriches prefer the drier parts of the park, while the tiny Günther’s and Kirk’s dik-diks are ubiquitous throughout.

The same diversity of habitats supporting Meru’s assortment of mammal species makes the park exceptionally attractive to birding enthusiasts. Over 400 species have been recorded here, with everything from wetland birds to grass and woodland specials. Pel’s fishing owls lurk beneath the canopies of the dense river trees, and recent sightings of threatened Hinde’s babblers in the park had birders aflutter. Other birds of particular interest include African finfoots, red-necked falcons, three-banded coursers, Somali bee-eaters, golden palm weavers, Boran cisticolas and black-billed wood hoopoes.

Explore & Stay

Want to go on safari to Meru? To find lodges, search for our ready-made packages or get in touch with our travel team to arrange your safari, scroll down to after this story.

Though the safari experience in Meru matches, if not outstrips, that of many of Kenya’s more popular safari destinations, visitor numbers to the park have remained low. The result is an extraordinary sense of true wilderness that the Kenyan Wildlife Service describes as “brilliant on a magnificent scale”. From the vantage point of one of the many rocky outcrops, travellers can look out across the diverse scenery without another person in sight.

The park is easily accessible via the tar road from Nairobi or direct flight to an airstrip. There are several well-maintained public campsites for those looking to explore on a budget. The roads are generally in exceptional condition, and navigating the park is made simple by sign-posted junctions.

Though Meru is open throughout the year, the best wildlife viewing occurs during the long dry season from June until September. Like much of East Africa, the park experiences two rainy seasons: the long rains from March until May and the short rains in October and November. The long grasses during the rainy season can make it difficult to see animals, and elephants often move out of the park along ancient migratory paths to the north. Given its Equatorial position, daytime temperatures vary little throughout the year, and the days in Meru are usually hot and often dry.

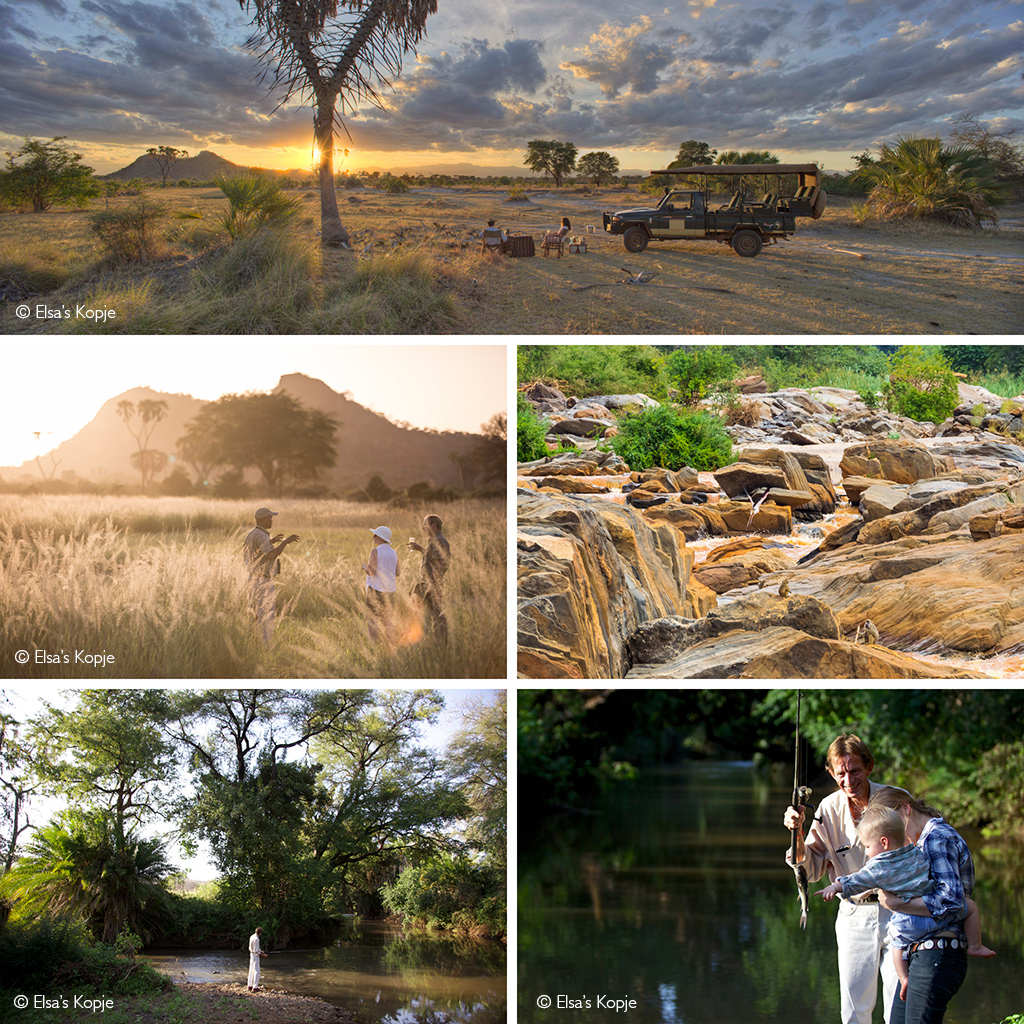

There are several other activities in and around the park for those with spare time (or for whom the excitement of daily game drives has palled). A trip to Adamson Falls, where the Tana River is forced through a narrow rock valley, is a popular attraction. Walking safaris offer the perfect opportunity to take in the scenery at a more sedate pace.

Further afield, outside the confines of the park, riverboat tours of the Tana River, fly camping, fishing and horse- and camelback safaris are all options for more intrepid tourists.

For those looking for a more luxurious experience, several tiny boutique lodges and camps in and around the park are perfectly positioned in some of the most scenic parts of Meru. The quiet and intimate arrangement makes Meru a perfect destination for families with children.

A land triumphantly reborn

It is common for travel articles on Meru (and many other parts of Africa) to describe the park as “unspoilt”. This is an understandably attractive representation – one which recreates the ‘blue chip’ documentary feeling of a vast wilderness untouched by human influence. But Meru is not untouched or unspoilt and to describe it as such is to understate the effort that has gone into undoing the damage of history.

Instead, Meru National Park is an extraordinary expanse of vital Kenyan wilderness, restored and resilient. And in the process, it has returned once again to a safe and immersive safari destination – a land reborn.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()