Mongooses of the desert

The sands of the Kalahari dunes are thick and soft – murder on the calves of the uninitiated – especially after a day spent following meerkats, feeling ungainly in their light, scampering presence. I was with a reserve meerkat monitor, and we were returning to the burrow ahead of the energetic foraging team in order to witness the reunion between adults and the pups left behind. As the sun began to dip, we arrived at the burrow to find it abandoned and silent. Worse still, I spotted a thick and unmistakable snake track cutting through the sand into one of the main tunnels. A glance into the gloom revealed a sinister, scaly head.

I was silently devastated, having watched the four tiny pups suckle from their mother just a few hours earlier. My heart clenched as the rest of the meerkat mob arrived, chattering and racing anxiously from entrance to entrance, searching for their youngest members. The night was drawing in, and temperatures were plummeting when one of the meerkats gave an excited chitter and raced off through the silky Stipagrostis grass.

We followed them to another set of tunnels, about 500 metres away, just in time to witness the joyous reunion as the four pups emerged and dived into their mother’s warm embrace. Their two young babysitters, without help or guidance and not yet fully grown themselves, had ferried the youngsters away from the snake to the safety of a new burrow.

Of all the endearing traits of the charismatic meerkat, it is their altruism that is perhaps their most attractive. Their complicated, soap-opera-like lives embroiled in trials, triumphs, and tragedies have entrenched them in hearts and minds the world over. From intense battles to complex alliances, these tiny creatures have enormous personalities (or the animal equivalent).

Introduction

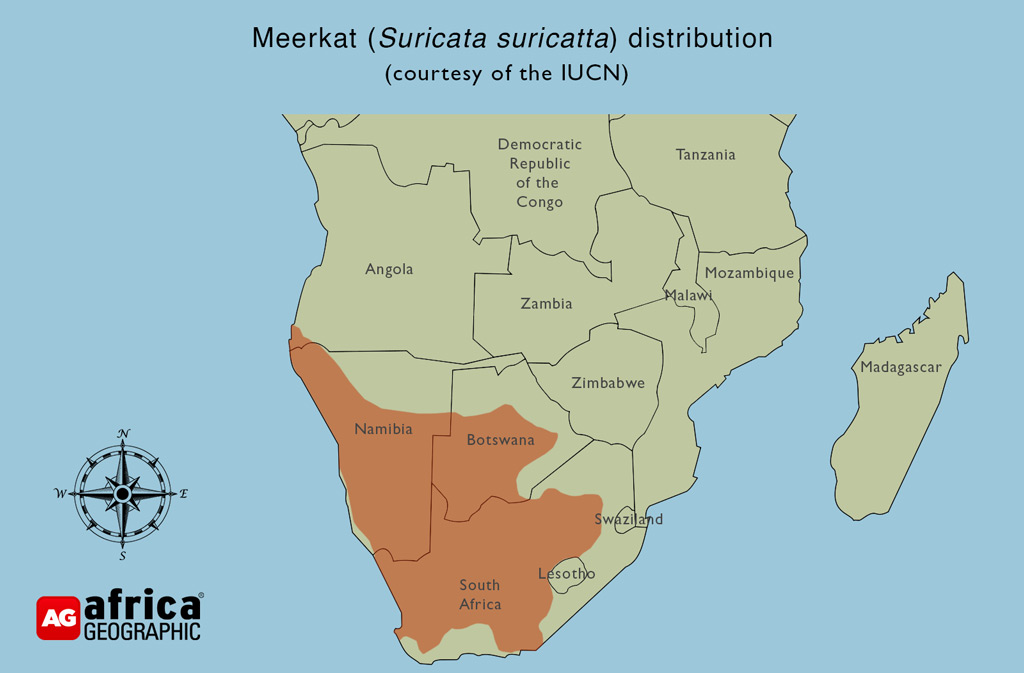

The meerkat (Suricata suricatta), or suricate, is a small, desert-dwelling mongoose found across the more arid regions of Southern Africa. These attractive little characters are known for their complex and intriguing social lives and are categorised as eusocial, the highest form of sociality in the animal kingdom. Each meerkat takes responsibility for the good of the clan as a whole. They are phylogenetically grouped with other social mongooses (like banded and dwarf) in a specific clade of the Herpistidae family.

Though they are one of the smaller mongooses, what they lack in size, suricates make up for in attitude and powerful curiosity. They have a phenomenal sense of smell, and their front paws are highly adapted for digging and foraging. A generalisation in nature is that the more social animals in a particular group are, the higher the intelligence (as we understand it). Meerkats fit this pattern very neatly. They can coordinate as a group when problem-solving but have also been shown to use individual thought and rationalisation in the process.

Meerkats defend territories of around 5km2 of open habitat with minimal woodland cover available for shelter. They move between various burrow systems within their territories and rely on their highly tuned eyesight to keep them safe from aerial and terrestrial predators. While their coats are perfectly coloured to blend with their desert surroundings, the dark rings around their eyes are believed to reduce glare. Members of the group take turns keeping watch while others forage. The sentinels give off specific vocalisations for different threats.

Quick facts:

| Social structure: | A mob/clan of between two and 30 individuals |

| Mass: | 0.62-0.97kg (dominant females may be heavier) |

| Length: | 24-35cm |

| Gestation period: | 60-70 days |

| Number of young: | three to seven pups |

| Average life expectancy: | five to 15 years (record in captivity is over 20 years) |

Pocket-sized predators and fierce fighters

Like all mongoose species, meerkats are lithe and efficient predators. Though most of their diet consists of insects, they will also eat other arthropods, reptiles, small birds, and eggs. Meerkats are water independent and meet their moisture needs through ingesting plant and fungal material, including assorted fruits, roots, tubers, tsamma melons and even Kalahari truffles.

There is a common misconception that meerkats, as part of the mongoose family, are immune to both snake and scorpion venom. This is not entirely accurate, and while they may have a level of resistance to some toxins, a sting from a Parabuthus scorpion or bite from a venomous snake could seriously compromise, if not kill a meerkat. They rely on lightning-fast reflexes to tackle dangerous prey like scorpions and remove the tail as quickly as possible. They then rub the exoskeleton on the sand to scrape off any remaining venom that may have sprayed in the process.

Members of the clan often mob dangerous snakes, especially near burrows. A rallying cry from one of the clan will bring the rest of the family rushing with tails upright and teeth bared, bristling with irritation. They surround the snake and take turns rushing it while the others stay just outside striking distance. More often than not, even the most venomous snakes will admit defeat and slither away from the barrier of sharp teeth.

Desert survivors

Surviving the extremes of a desert requires specific adaptations, including excellent thermoregulation and water conservation. Research has shown that meerkats have a remarkably low basal metabolic rate compared to other carnivores, which in turn helps conserve water. When the temperature drops overnight, their heart rate and oxygen consumption drop to save energy and they huddle together, sheltered by the microclimates of their tunnels.

Alpha autocrats and altruism

The true secret to the meerkat’s survival strategy is their social structure, which is highly organised and, most importantly, based around cooperative breeding. Like any other mammal social grouping, the more individuals there are in a group, the more complex their pecking order and intrapersonal relationships. This is especially true in animals such as meerkats, hyenas, or primates, where the group consists of related and unrelated individuals.

Meerkats have a strict dominance hierarchy and are ruled by the iron fist (claw?) of the dominant male and female. These coveted positions are usually held by older individuals and often acquired through physical combat or sustained aggression and assertion. Only the dominant female will breed, and when the pups are born (usually around the rainy season, but birth can be at any time of the year), the clan’s life revolves around protecting, feeding, and nurturing them. Pups from a subordinate female could divide the clan’s attentions – a risk that the dominant female is seldom prepared to tolerate. It is not uncommon for her to kill pups other than her own or ostracise the disgraced subordinate mother (even if it is her own adult daughter).

Of course, the biological drive to reproduce is potent. Subordinates are faced with three options: wait it out, disperse, or risk a sneaky liaison. Both males and females do disperse, but females are less likely to do so. Instead, they usually choose to linger in the hope of a chance at the top spot. Males may disperse alone or in coalitions and search for an existing group to join. It takes time to be accepted into a new clan, but the males have a far greater chance than emigrant females. Other males have found a slightly less permanent solution to the problem and have been observed sneaking off into rival territories searching for willing females. These rascals have found a way to have the best of both worlds – fathering pups without having to leave the clan. Astonishingly, one study suggests that around a quarter of meerkat pups in the whole population are sired in this manner.

And baby makes three (and four and five and…)

A dominant female may have up to four litters in the space of a year, so a meerkat clan is almost constantly involved in raising youngsters. Subordinate females, denied pups of their own, will even suckle the dominant’s offspring. Meerkat pups are astonishingly cute, especially when they first emerge from underground at around 16 days. They begin foraging with the adults some ten days later. After a few initial wobbles as they find their feet, meerkat pups race around bow-legged from adult to adult, chittering and begging for food. They learn vital skills in this way, especially when finding food and tackling more dangerous prey. An adult will remove a scorpion’s tail and then leave the pup to figure out how to tackle the pincers.

Everybody’s talking

Meerkats are highly vocal and chatter away to each other almost constantly throughout the day. Their most common vocalisations are used to communicate while foraging so that every member of the group stays in contact with the others. This broad repertoire also includes alarm calls specific to different predators – a jackal, for instance, will provoke a distinct sound and reaction compared with those for an eagle. Meerkats are also able to communicate distance and urgency or recruit members to mob a snake.

Famously, the fork-tailed drongos have learnt to capitalise on this tendency. These shiny, black birds are notorious mimics, and through observation, some individuals have learnt to imitate the alarm sounds that send meerkats rushing for cover. The drongo will bide its time until the meerkat has secured a juicy meal before causing pandemonium and swooping in to claim its prize. So why don’t the meerkats learn? Research shows that some drongos can produce over 30 different alarm calls, including their own “drongo-specific” cry for genuine threats. They rotate between them and make sure to give off an alarm call for real predators. In short, the meerkats cannot afford to ignore the drongo that cries falcon, even if they know that they may be hoodwinked.

Final thoughts

For the last three decades, researchers at the Kalahari Meerkat Project have been studying sixteen groups of meerkats over multiple generations. Their work has offered unparalleled insight into the daily lives of these intelligent mongooses and the generational battles that play out across the years.

From Meerkat Manor to Timon in The Lion King, meerkats have scampered their way across popular culture. While much of their portrayal usually comes with a great deal of anthropomorphism, the truth is that the meerkats are surprisingly relatable animals. From acts of astonishing bravery to treacherous moments of betrayal, life in a meerkat mob is never dull.![]()

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()