A colourful character

One relatively inauspicious day in May 2005, the alpha male mandrill at the “Monkey Islands” exhibit in the Chester Zoo in England stunned the researchers who had been filming his movements for a behavioural study. JC, a 12-year-old Czech-native (or at least, born at Usti Zoo in the Czech Republic), was observed breaking twigs, bark, sticks and wood chips and then using the splinters to clean his toenails. Unbeknownst to him, his primate pedicure was to make headlines the world over: JC had just demonstrated the necessary cognitive ability to create and manipulate a tool for a specific purpose.

Thus, the mandrill joined the elite ranks of non-human primates known to use tools alongside chimpanzees, bonobos, gorillas, and a couple of other monkey species. JC’s pursuit of good hygiene proved that the world’s largest monkey species is more than just a pretty face (in a somewhat flamboyant outfit).

Introduction

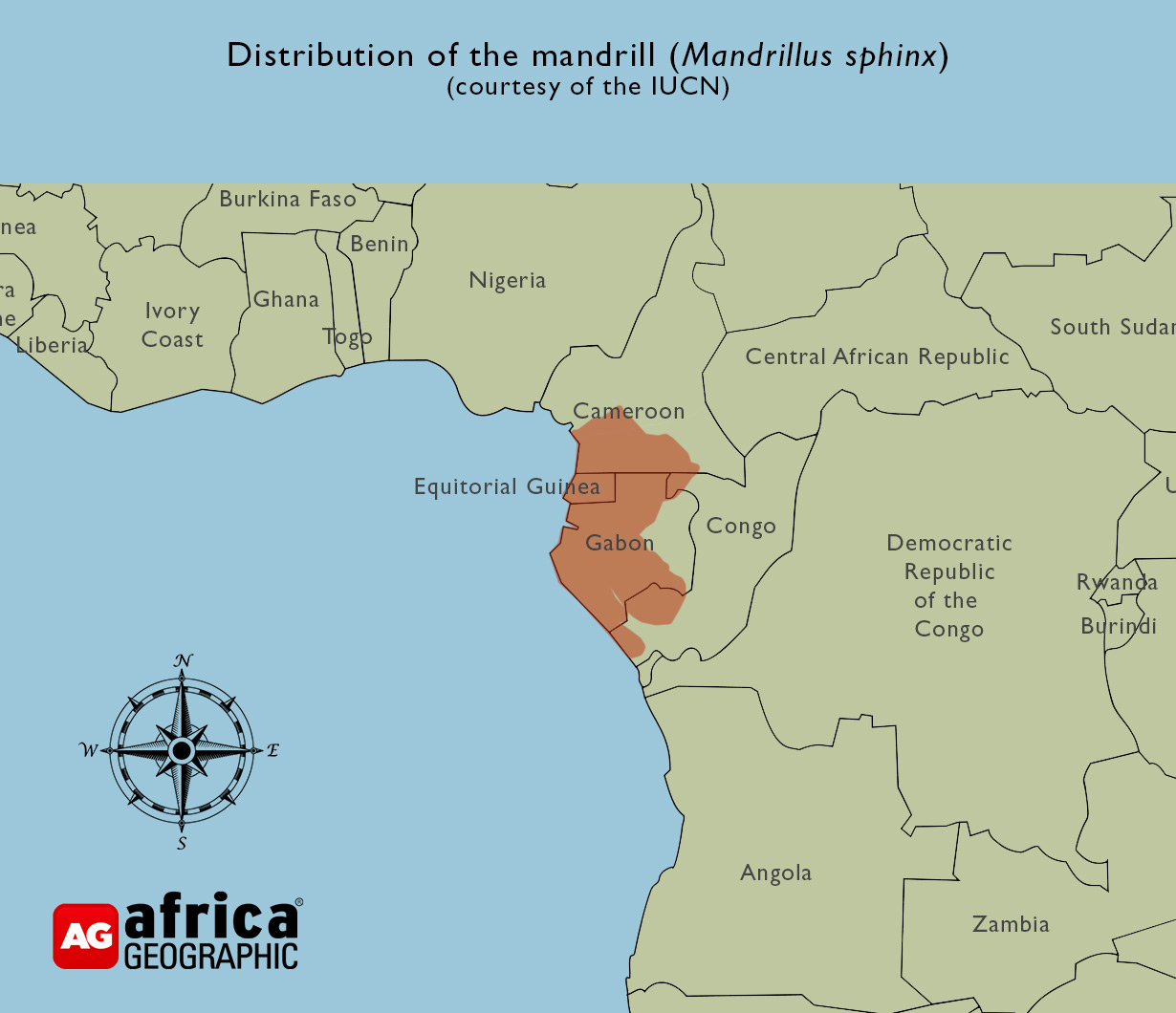

The mandrill (Mandrillus sphinx) is a large, almost tailless monkey confined to the tropical rainforests of southern Cameroon, Gabon, Equatorial Guinea, and the Republic of the Congo. Their morphology is superficially similar to that of baboons, so both mandrill and drills (Mandrillus leucophaeus) were once considered to be part of the Papio genus. They have since been reclassified as the only two species belonging to the Mandrillus genus, and researchers have confirmed that they are more closely related to the much smaller mangabey species.

Chacma baboons and mandrills are similar in size – the chacma baboon is fractionally taller and longer, but mandrills are heavier, more compact, and muscular. Mandrills display considerable sexual dimorphism, with the males being almost triple the mass of the females. The ferocious-looking males weigh an average of 32.3kg, with some massive individuals recorded at over 54kg. Like baboons, the mature males sport enormous canines of around 6cm (longer than those of a leopard). These they use to intimidate aspiring rivals and deter potential predators.

Mandrills are omnivorous and feed on over a hundred different plant species, with a particular preference for fruits where available. They also consume various invertebrates, eggs, birds, and reptiles and are known to hunt small antelope and rodents. They spend most of their days foraging on the ground but are equally comfortable in forest canopies, leaping from tree to tree with an agility that defies their considerable bulk.

Multicoloured monkeys

Not only are the males larger than the females, but they are also more lavishly adorned in a spectrum of vivid colours. A strip of crimson runs down the middle of their elongated muzzles and extends over their lips, flanked by a pair of electric blue ridges. A bright yellow goatee spreads down across their chests and up over their shoulders as they mature, blending with tufts of white into an impressive mane. One would think that this alone would be sufficiently eye-catching, but both ends of the male mandrill are equally flashy. Their rainbow rumps are coloured red, pink, blue and purple in what has to be one of the least subtle examples of sexual signalling in the animal kingdom.

Such gaudy displays of colour, while prevalent in many bird species, are uncommon in mammals. Primates are one exception to this rule, and many different monkey species have colourful genitals. However, the mandrills’ colouration is so over-the-top that even Charles Darwin noted that “no other member in the whole class of mammals is coloured in so extraordinary a manner.”

A male mandrill’s ensemble is directly related to his testosterone levels and dominance within a strict social hierarchy. If a male successfully challenges an alpha, his testosterone levels will rise, and the red colours will become more vibrant. His genitals will increase in size, and a gland on the sternum will secrete an odour designed to tempt females. These dominate males are known as “fatted” males. Conversely, a fall from grace will mean the opposite for an unfortunate male as he gradually becomes “nonfatted” once again.

Scintillating sociability

One theory behind the males’ excessive colouration is that it evolved to compensate for exceptionally high competition between males – essentially a method of conflict avoidance in the gloomy rainforest habitat. A group of mandrills is referred to as a ‘horde’ – a large and stable troop consisting of females, offspring, and young males. Research from Lopé National Park in Gabon calculated an average horde size of 620 individuals, with some hordes numbering up to 845 mandrills. One group of researchers counted 1,300 mandrills in one group, making it the single largest non-human primate aggregation ever recorded.

Mandrills are usually found in challenging habitats for bipedal researchers. This, combined with their natural shyness, has made it difficult for scientists to observe mandrill behaviour in the wild consistently. As a result, surprisingly little is known about their social structure. Most monkey troops demonstrate a strict social hierarchy, even between females. Fascinatingly, mandrill experts have yet to discern a consistent pattern of leadership, though it is clear that they have dynamic social networks and that certain females are central to the cohesion of the horde.

The females remain in their natal groups throughout their lives, while the males disperse once they reach maturity at around six years of age. Rather than forming bachelor groups, the males tend to live somewhat solitary lives outside of the breeding season. From June to October, when the females are in oestrus, the males join the hordes and follow their own strict, linear hierarchy. DNA analysis of one horde indicated that the alpha males of hordes had sired 80-100% of the offspring over five years. Disputes between males are usually resolved through posturing and threat displays, but the rare fights between equally matched males are brutal and, occasionally, fatal.

As with other monkey species, grooming plays a vital role in reinforcing the bonds between horde members and winning favours from the alpha males. Both males and females are highly vocal, expressing themselves through various sounds from mighty roars to expressive grunts and screams. Naturally, the bright colouration also serves to emphasise body language cues and facial expressions. The famed “silent bared-teeth face” is just one of their many varied communication methods, with most researchers agreeing that despite appearances, this is not an aggressive body language cue.

Protected primates?

In the wild, leopards are the mandrill’s main predator, though the likelihood of predation decreases as individuals mature. A large male mandrill is more than a match for most leopards, and males exposed to models of leopards were observed to pace back and forth, baring their impressive teeth in a threat display. Birds of prey, notably crowned eagles, and snakes also pose a threat to incautious youngsters. Interestingly, when presented with a potential threat, these otherwise noisy primates seem to follow a silent cue and noiselessly melt away into the forest canopy.

Despite limited natural predators, the mandrills are listed as ‘Vulnerable’ on the IUCN Red List. While there are no current population estimates available, researchers believed that their numbers might have decreased by more than 30% over the past 24 years. This is partly due to wide-scale habitat destruction across most of their natural range but has been compounded by the more immediate threat of subsistence hunting. Mandrills, particularly large males, are a prime target in the bushmeat trade. They are a long-lived species (with a lifespan of over 30 years in captivity) and are slow to mature, so sustained hunting pressure has had a pronounced effect on their populations.

For the same reasons, the mandrill’s close cousin, the drill, is under even more pressure, and they are now one of the most threatened of all mainland Africa’s primate species. There are believed to be fewer than 4,000 left, scattered in fragmented populations in Nigeria, Cameroon, and Equatorial Guinea. Even though the mandrills and drills are listed under Appendix I of CITES and protected by national legislation across their range, these spectacular monkeys face an uncertain future.

Like gorillas, the mandrill’s best hope of survival lies in their tourism value. Fortunately, the largest populations of mandrills are still flourishing in Gabon’s protected forests. At present, there is only one habituated horde of wild mandrills in southern Gabon. There are plans in place to collar and habituate more hordes as part of a larger move towards improving ecotourism opportunities in Gabon. These last remaining sanctuaries offer eager tourists the best opportunities to meet with one of Africa’s most intelligent, colourful, and fascinating monkeys.

Conclusion

We still have much to learn about mandrills, and unravelling the complexities of their social lives promises to be a fascinating process. As intelligent primates living in enormous social groups, their individual relationships, kin bonds, and hierarchies must be dynamic and complicated. As JC and his clean(ish) toenails demonstrated, mandrills still have the capacity to surprise us and probably will for a long time to come.![]()

View this photographic gallery The Painted Ape.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()