A photo journey through the Mara

- Photographer Irene Amiet’s photo journey through Maasai Mara during the Little Rains brought incredible wildlife experiences and photos.

- Maasai Mara’s Little Rains typically arrive in November.

- Visiting during the Little Rains brings richly layered photographic moments.

- Fewer visitors during the shoulder season allow for quieter sightings and more considered photography.

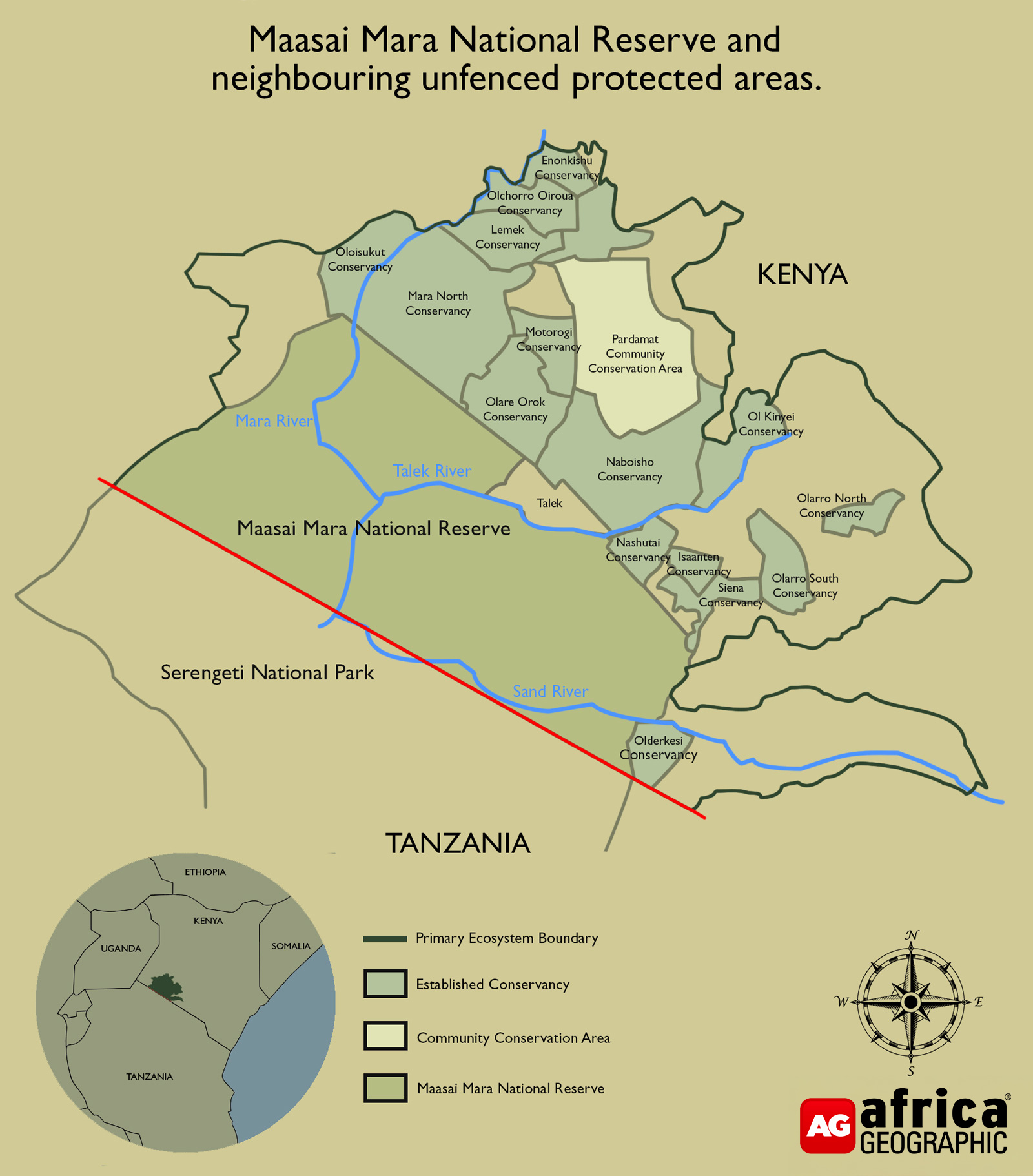

Photographer Irene Amiet arrived in Kenya’s Maasai Mara National Reserve during the ‘Little Rains’ that typically come in November, drawn by the promise of shifting light, open horizons and encounters shaped as much by weather as by wildlife. Visiting this popular safari destination outside of peak season brought a truly unique experience away from the crowds. Moving between storm and silence, solitude and spectacle, her journey unfolded across plains where predators linger, giraffes drift like apparitions and the vastness of the landscape reframes both photography and presence. Irene stayed at Oltepesi Tented Safari Camp, where there are no fences between the park and the community land, and wildlife roams throughout the area.

Want to visit Maasai Mara National Reserve for a photographic safari? Check out our ready-made photographic safaris here, or browse our other safaris to Maasai Mara here.

Want to visit Maasai Mara National Reserve for a photographic safari? Check out our ready-made photographic safaris here, or browse our other safaris to Maasai Mara here.

“In the opening paragraph of Out of Africa, Karen Blixen pays homage to the giraffe’s mystical, otherworldly grace. After many encounters with these animals across southern Africa, it was only on my first visit to Kenya’s Maasai Mara that I finally understood them in a landscape that gives Blixen’s words their full measure. Kenya’s vast skies hold giraffes suspended somewhere between heaven and earth.

It is these wide-open plains, rolling endlessly into the distance, that tell the giraffe’s story best. Here, where weather is the composer to whose score animals, rivers, trees and grasses conduct their lives, it is the giraffe that commands the horizon.

We chose to arrive in late October, at the very start of the Little Rains – a time to smell thunder long before clouds finally drench the savannah, and to witness the restless play of sun and storm beneath which one can chase endlessly changing light.

Roads, valleys and the pulse of Kenya

For a long time, I had been almost shy of visiting Kenya because of the number of people it attracts. I am selfish in nature, seeking quiet – the sounds of birds, the wind in the grass, the lion’s call at night – uninterrupted by crackling radios and an armada of four-wheel drives.

But curiosity eventually won. A good friend showed us images taken around his camp – visual nuggets that drew me, like so many photographers before me, into the Mara’s imagery gold rush. From the moment our vehicle left Nairobi and crossed the escarpment, with the Kedong Valley unfurling far below, I was utterly captive to the land.

Shacks clung precariously to the abyss, and with each daring overtake in busy traffic my heart galloped faster. It was the adrenaline of African roads, a reminder that life here feels both more intense and more fragile. Four hours later we left the tar behind and began our bone-rattling journey to Aitong.

Woken from a slumber, I opened my eyes to herds of cattle scattered across green hills, among them the occasional zebra. Children ran alongside our vehicle through villages, waving and laughing, while women stood by the roadside dressed in brilliant turquoise and red – beacons of grace in a roughened world. This contrast between hardship and beauty, perseverance and an often-unforgiving environment, is woven into the land’s very essence.

Just as cheetahs move alone at noon – active when larger, stronger cats sleep, exploiting the hottest hours when others seek shade – so humans find their own niches, shaping lives and strategies against the odds.

What awaited us on the journey ahead was a landscape alive with presence and promise: hippos lingering in quieter reaches of the Mara River, their rounded backs breaking the surface as water slid steadily past; elephants moving across open plains, their vast forms set in stark contrast against towering, storm-filled skies; cheetahs following solitary paths through heat and light, unhurried and intent; and lions everywhere: resting on termite mounds, pacing the grasslands, emerging from the rains with new zest.

Under the spell of the Little Rains

The Little Rains, shorter and less predictable than the long rains, usually fall between late October and early December, often delivering the essence of several seasons in a single day. Downpours transformed the grasslands from bristly doormats into silken carpets of fresh shoots. Lions stoically waited out the rain, just as we sat huddled in our waterproofs, watching them watching us. When the breeze wiped the clouds clean, the lions stood and shook their manes into brilliant watery halos, while cubs pranced about on wet paws, flicking droplets across their mother’s nose.

Predators, patience and the open plains of Maasai Mara

Our first cheetah appeared at sunrise, a wandering silhouette pacing the horizon. When we found her again later, she stood sentinel beside a lone tree – two living forms, protagonists in a midday play. Only an open landscape creates such opportunities for contrast, and already I was grateful we had come.

From before sunrise to after sunset, our days stretched into 13-hour marathons in an open Land Cruiser custom-built for photography, with low hatches, open sides and an exposed roof. Never did I feel confined. Driving across the Mara, with the horizon spreading in every direction, the landscape seemed to transcend the body itself; the breeze might just as easily have carried me aloft. The world felt full of treasure, and our task was to capture those gems on camera.

At times, we were utterly alone. We could blink and imagine ourselves back in Blixen’s Africa – until our guide, James, dropped the vehicle into gear and rallied us across the plains toward a sighting. First come, first served: positioning was everything.

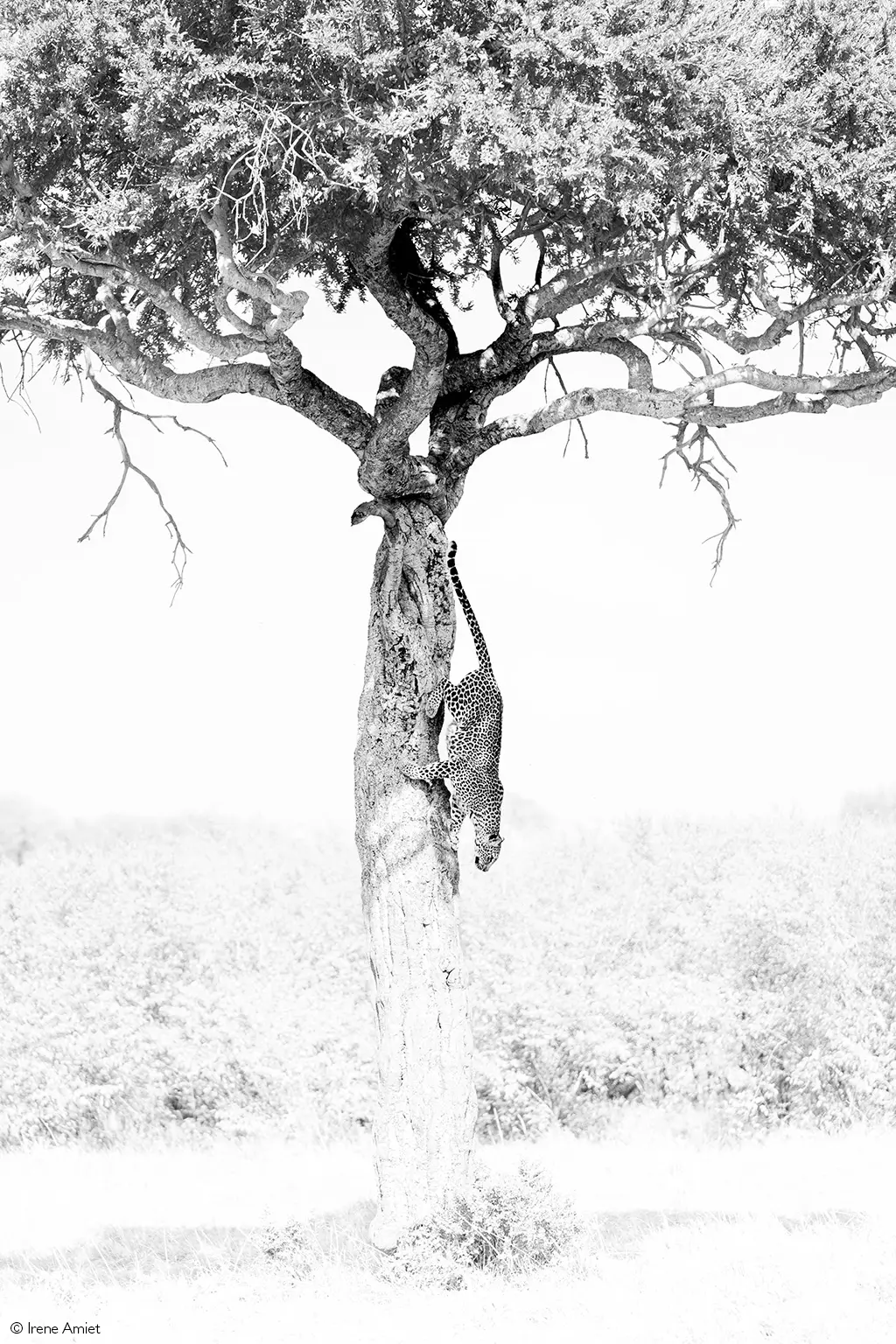

There she was – a leopard draped high in a tree. Studying the trunk, we noticed a subtle lean that created a diagonal ledge, a likely route for descent. We positioned ourselves and waited. And waited.

Vehicles began to arrive. Some left after half an hour, but more continued to gather until nearly thirty surrounded the tree on three sides. The fourth remained clear, thanks to radio communication that preserved a clean backdrop. The leopard dozed on. When she shifted, a hundred cameras lifted in unison, only to sink again as she resettled and slept. Two hours later, movement – first a yawn, then a fluid descent, exactly where we had hoped.

How, in a setting filled with competing languages, buzzing radios and the machine-gun chatter of older camera shutters, did the wild heartbeat we crave on safari still endure? Because beyond the carousel of vehicles, far out on the horizon where clouds once again sculpted the sky, the Mara stretched wide and untamed. We were merely passing through. The leopard had occupied her tree a hundred years ago, and – if we do her justice – her daughter’s daughters will be there long after us. The scene amused me, a quiet reminder of humanity’s absurdity: our tendency to rush, stage and collect, often removed from reality itself.

When the sky clears and giraffes sail past

When the rains finally moved on, the sky invited us to play. I mentioned to James that a clear sunset was shaping up, and twenty minutes later – after another race across hills, through two rivers and a strip of woodland – he delivered me to a plain where I could frame a topi against the setting sun, seconds before it vanished in fire.

Letting go of the adventure-sport rush of photography in favour of quiet artistry is not always easy. What followed, however, was a procession of giraffes gliding past in the twilight, small stones rolling softly beneath massive hooves. Their passage was almost soundless, like ghost ships at night – there, then gone – vast forms dissolving into silhouettes, swallowed by distance.

The crowds, the rush of the day, all fell away. What remained was the image Blixen had evoked more than sixty years ago, glowing steadily in my heart. And in that moment, I knew I had finally met these wondrous creatures.”

Irene stayed at Oltepesi Tented Safari Camp for her specialised photographic safari? You too can join us for a photographer-guided safari to Oltepesi, guided by Arnfinn Johansen.

Irene stayed at Oltepesi Tented Safari Camp for her specialised photographic safari? You too can join us for a photographer-guided safari to Oltepesi, guided by Arnfinn Johansen.

Further reading

- The Maasai Mara is an iconic Kenyan safari destination that hosts the famous Great Wildebeest Migration and Big 5 wildlife action throughout the year.

- Kathy West’s trip to Maasai Mara for a week of slow-paced photography brought intimate wildlife encounters & a safari like no other. Read about Kathy’s unforgettable Maasai Mara safari here

- This interesting introduction to Kenya’s Maasai Mara will have you contacting Africa Geographic to book your next African safari. Read more about Maasai Mara here

- Busanga Plains, Kafue, is brimming with wildlife, yet not overwhelmed by tourists. Read Irene Amiet’s travel diary from this Zambian safari spot

- Traveller Irene Amiet visited Zimbabwe’s famed Mana Pools National Park to photograph the other-worldly wilderness of this Zambezi kingdom. Read about her trip here

About Irene Amiet

Irene Amiet is a Swiss-born writer and photographer whose work is shaped by years spent living and working across Africa, the Americas and Europe.

Irene Amiet is a Swiss-born writer and photographer whose work is shaped by years spent living and working across Africa, the Americas and Europe.

With a background in tourism and hands-on conservation, including rainforest advocacy in Panama and big cat research in South Africa, she brings field experience to her storytelling.

Her work is driven by a deep respect for wild places and a belief in storytelling as a tool for conservation awareness. Now based in north-west England, Irene co-owns a fine art photography gallery, contributes to international publications and returns to southern Africa whenever she can. Irene is also the founder of conservation publishing platform, Wilder World.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()