The emerald in Kenya’s crown

![]()

The Maasai Mara ecosystem is one of the most famous wilderness areas in Africa and one that attracts visitors from near and far. The breathtaking view of the sunrise from Oloololo (Siria) Escarpment, some 2,000m above sea level and 300m above the plains below, was forever etched into human memory by the film “Out of Africa”. Below the mountains, the Mara River winds its serpentine route to the south, hidden beneath groves of riverine trees, and the fields of red oat grass stretch as far as the eye can see. It is from here that one can really understand why the Maa people of the area referred to this place as “Mara”, which, literally translated, means “spotted” or “mottled” – concerning the trees and clumps of vegetation that dot the landscape.

Scenically, the Maasai Mara is one of the most beautiful places on the planet. The dawn light is a photographer’s dream: golden and soft. Rather than detracting from the natural beauty, the multicoloured hot air balloons drifting silently through the air add something fantastic to the morning atmosphere. For centuries, the Maasai people have shared this land with their wild neighbours – look carefully, and you will find the ancient grooves of the cattle paths worn by millions of bovine hooves marking the routes to salt licks still used today. Look even more carefully, and you might just find an abandoned old Volkswagen bus hidden in a secret valley known only to a few observant or lucky souls.

The facts

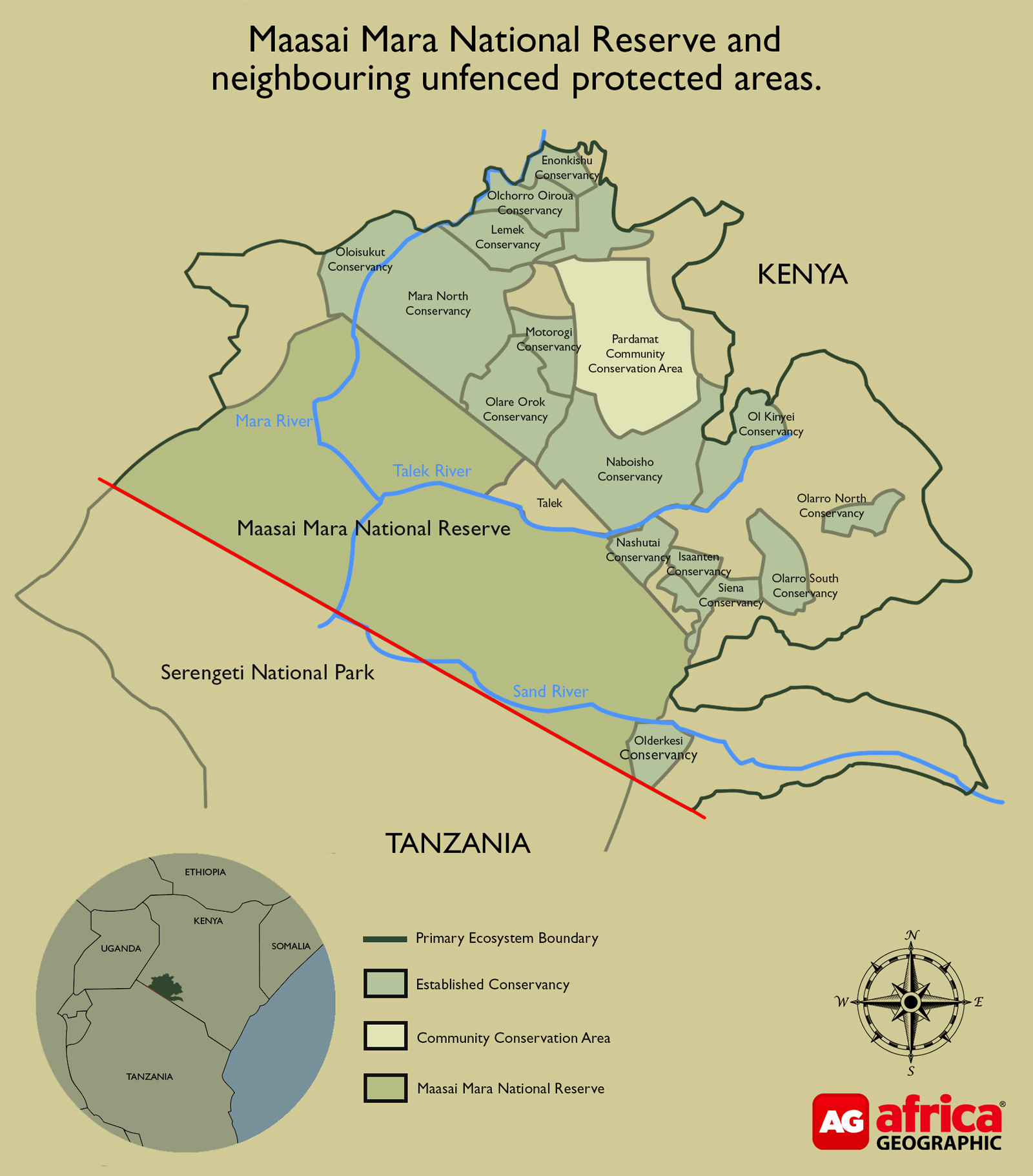

The combined area under conservation in the Maasai Mara ecosystem in Narok County amounts to almost 3,000km² (300,000 hectares), which is split evenly between the Maasai Mara National Reserve (150,000 hectares) and various community-owned conservancies that share unfenced boundaries. This Maasai Mara ecosystem shares unfenced borders with Loita Plains to the north and east and the Serengeti to the south, in Tanzania.

The Mara Triangle on the western bank of the Mara River comprises one-third of the Maasai Mara National Reserve. It is run by the TransMara County Council and managed by the Mara Conservancy. The remaining two-thirds of the Reserve, on the eastern side of the Mara River, is run by the Narok County Council.

Community-owned conservancies currently make up more than 140,000 hectares, with additional land under negotiation. The current conservancies are:

| Olare Motorgi | 133km² (13,000 hectares) |

| Mara North | 260km² (26,000 hectares) |

| Lemek | 24km² (2,400 hectares) |

| Naboisho | 200 km² (22, 000 hectares) |

| Enonkishu | 40km² (4,000 hectares) |

| Ol Kinyei | 70km² (7,000 hectares) |

| Nashulai | 24 km² (2,400 hectares) |

| Olchorro Oirowua | 64 km² (6,400 hectares) |

| Olderkesi | 100 km² (10,000 hectares) |

| Oloisukut | 93km² (9,300 hectares) |

| Pardamat Conservation Area | 260km² (26,000 hectares) |

| Siana | 40km² (4,000 hectares) |

| Olarro North and South | 100km² (10,000 hectares) |

The concept of individually- or community-owned conservancies should be considered a Kenyan conservation success story. The rangelands surrounding the National Reserve were once cattle grazing lands, but now the communities of landowners rent out the land to tourism operators, and the wildlife is protected. Tourists that visit the conservancies play an enormous role in ensuring the future of these protected wilderness areas by ensuring a continuous revenue stream for the local communities. Given that the use of the land is reserved for paying tour operators, it also means that visitors to these areas are treated to a more exclusive safari experience. With over 65% of Kenyan wildlife existing outside of government-protected wilderness areas, it is easy to see why conservancies will be critical to conservation efforts in the future.

Beyond the migration

The Great Migration is one of nature’s greatest spectacles. Every year from around July until October, over a million wildebeest, zebra, topi, eland and Thomson’s gazelle make the treacherous journey from the Serengeti into Maasai Mara. Driven by their quest for food, they flow across the landscape and are forced across crocodile-infested rivers: battling currents and leaping over hippo only to be forced to dodge the predators waiting on the opposite bank. It is a chaotic, adrenaline-inducing smorgasbord of survival instincts on a knife-edge and the predators throw themselves into the melee with joyous abandon, so witnessing a kill is almost guaranteed.

That said, there is far more to the Maasai Mara than the migration. All year round, wildlife enthusiasts are treated to spectacular sightings of the Big 5 and the cheetah sightings are astounding – the now-renowned of five males deserving of a special mention. The Mara is home to some of the largest hyena clans in Africa, and while the highly endangered black rhino number only a few, they are there for those who know where to look. Many visitors have found themselves delighted not only by the larger animals but also by courageous jackal, cheeky bat-eared foxes and graceful serval, as well as the striking crowned cranes and ubiquitous secretary birds.

The experience

From rustic campsites to lodges that epitomize luxury, the Maasai Mara has something to offer every taste (and an array of varied budgets), but the knowledge of experienced guides can make the difference between a good safari and a once-in-a-lifetime adventure. Guides know the weather, the area, the best (and worst) roads and the animals, and they can use that information to make informed decisions. A canny visitor (or guide) can use the topography to their advantage during the high tourist season by using crests and viewpoints to spot sightings from a distance but during the quieter times, finding animals often requires more effort and skill. A particularly good time to visit the Mara is just after the departure of the migration: the grass is shorter; the predators often experience a ‘baby-boom’, and there is far less pressure from other safari vehicles. The Maasai Mara experience also lends itself to women planning their safari – alone or in groups.

The Mara is enormous and covering ground is essential to experiencing the beauty of this ecosystem in its entirety. The days may be long, but nothing is as refreshing as lunching beneath the boughs of an ancient fig tree, languishing in its shade and perhaps speculating as to how much history the fig has witnessed over its long life. The rains are biannual – the “short rains” usually arrive around November and dissipate sometime in January and then the “long rains” begin again in April until around June. The weather, however, is unpredictable and torrential downpours and afternoon thunderstorms are not uncommon. Getting stuck up to the axles in black cotton soil is part of the Mara experience and should simply be accepted in the spirit of adventure.

For the most part, the afternoon thunderstorms dissipate just in time for another Mara treat: the sunset. With the dust of the day washed away by the rain, the landscape is once again drenched in gold, this time with the faintest of pinkish hues. The extraordinary beauty of the Maasai Mara and its abundance of wildlife make it deserving of its reputation as one of the most exceptional safari experiences in Africa.

Want to go on safari to Maasai Mara? To find lodges, search for our ready-made packages or get in touch with our travel team to arrange your safari, scroll down to after this story.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()