THE STORY OF A LITTLE PANGOLIN WHO'S MAKING A BIG DIFFERENCE

Katiti, which means “little one” in the Herero language, might be the luckiest pangolin alive.

One of my favourite encounters with one of these curious creatures was in Botswana’s Kwando Reserve, just south of Namibia’s Caprivi Strip. “Pangolin! Pangolin! Pangolin!” came the excited cry as our guide, Mark Tennant, gunned the safari vehicle towards a distant group of wild dogs bouncing up and down like pogo sticks in the long grass. As we got closer I counted five dogs, all atwitter as they danced about – in response to what I could not see.

“Call me sceptical,” I muttered from the seat beside him, “but how do you know there’s a pangolin there?”

“That’s what wild dogs do when they find a pangolin!” came Mark’s breathless explanation. And sure enough, there it was, a Cape pangolin curled up in a perfect, armoured ball.

Realising they could do nothing with the pangolin in its protective mode, the wild dogs made off. But instead of following the dogs on their hunt, our eight safari-goers decided to spend time with the pangolin. Such is the allure of this elusive creature.

It took ten minutes of awed silence for the shy creature to uncurl itself and amble off in that strange floating hovercraft way, unhurried and seemingly unperturbed by his groupies and their whirring shutters. It was broad daylight and although I am privileged to have seen several pangolins on this awesome continent I call home, this was one of my most memorable sightings. I am sure this pangolin lives on in those lucky people’s memories and photo albums.

But the hope is that they don’t only live in memory. The dominant news about Africa’s pangolins is that they are being harvested in great numbers to satisfy the voracious demand for Eastern food and medicinal cures. It’s not surprising that the Asian pangolin species are on the brink of extinction, and now the great Eastern tide is sweeping through Africa, hoovering up more and more of the little “scaled artichokes”. Learn more about the trade in pangolin meat and scales

A Cape pangolin was rescued from such a fate. She was captured (poached) and taken around a Namibian town in a box, no doubt to be sold on the black market. A shop owner felt sorry for the pangolin and bought her before passing her on to Maria Diekmann – founder of Pangolins International – who took it upon herself to rehabilitate the pangolin so it could be released into the wild.

Middle: Roxy rests her head on Maria’s shoulder. © Scott & Judy Hurd

Bottom: Roxy, the expectant mother. © Scott & Judy Hurd

As she was nursing the pangolin back to health and a strong bond formed, Maria named her ‘Roxy’. As hard as it was for Maria to watch her go, Roxy was destined to return to the wild, but not before leaving a precious gift: her son, Katiti. This gift has grown up and is now an invaluable source of data for efforts to understand pangolins better and to rehabilitate and return poached pangolins into the wild. Katiti is also a lucky charm.

Roxy was destined to return to the wild, but not before leaving a precious gift

Maria explained that after Roxy’s departure, Katiti’s condition deteriorated on his diet of ants and milk. After much experimentation and advice from Lisa Haywood of Tikki Haywood Foundation, the only other person known to have hand-reared a baby pangolin, Katiti’s health started to improve. After a few months, he has weaned off substitutes and foraging naturally.

He now sets his daily routine and forages in the wild for about five hours a day, returning to Maria for a well-deserved rest. He even interacts with the wild pangolins he comes across while foraging. A GPS unit has been attached to the scales on his back, and his every move is monitored for extra security and for collecting valuable data. The plan is to return Katiti to the wild eventually, and work is in progress on a more sophisticated monitoring unit that will send back even more vital information.

Middle: In typical pangolin fashion, Katiti rides on his mothers back for the first few months. ©Maria Diekmann

Bottom: Katiti finding his feet. ©Maria Diekmann

Just as valuable is Katiti’s role as a ‘comforter’ to recently rescued pangolins. This increases their chances of successful rehabilitation and release. Experience has taught Maria that immediately returning a confiscated pangolin into the wild, without rehabilitation, often results in the animal’s death. They have to negotiate past established pangolin territories and evade predators – a tough ask if they are injured, stressed or malnourished.

Katiti has taken on the role of ‘comforter’ to rescued pangolins

Two such pangolins were ‘Merel’ (2 years) and ‘Keanu’ (9 months), found together in an old metal drum where they were held for three days awaiting a buyer. They were cold and malnourished, and Keanu had a broken leg. Merel was successfully released, but Keanu died of complications picked up during the three days in the cold without food or water. Pangolins are particularly susceptible to pneumonia due to their lack of fur.

Another completely rehabilitated pangolin that Katiti helped nurse back to health was named ‘Coll’. Like Katiti, he was fitted with a GPS device and released on a neighbouring farm. His monitored wanderings provided valuable data before he died of natural causes – predation by a hyena or honey badger.

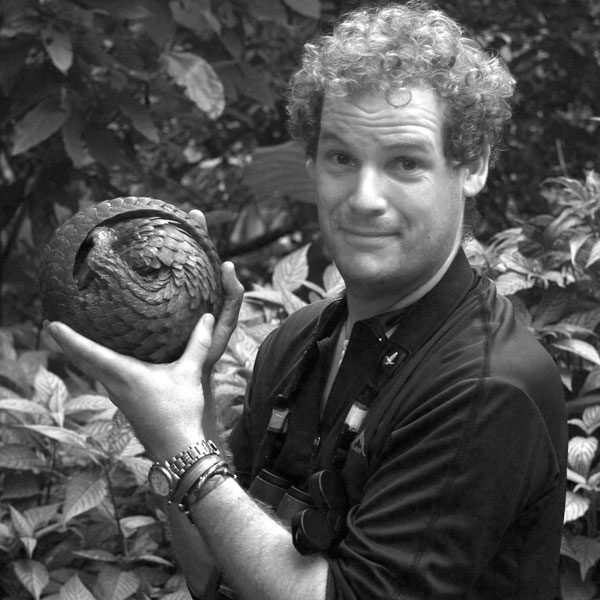

©Christian Boix

Apart from comforting other pangolins, one of Katiti’s most important roles is educating people and tugging the odd heart-string. Local Herero people have been thrilled to have their photos taken with Katiti. Importantly, some of those people are Herero chiefs who have returned to their communities, telling them that their picture with the pangolin brings luck to the community because a picture lasts longer than just the taste of meat. They are now motivating their communities to leave the pangolins where they belong, in the wild.

Contributors

SIMON ESPLEY is a proud African of the digital tribe and honoured to be CEO of Africa Geographic. His travels in Africa are searching for wilderness, real people with interesting stories and elusive birds. He lives in Hoedspruit, next to the Kruger National Park, with his wife Lizz and 2 Jack Russells. When not travelling or working, he is usually on his mountain bike somewhere out there. Simon qualified as a chartered accountant, but found his calling sharing Africa’s incredibleness with you. His motto is “Live for now, have fun, be good, tread lightly and respect others. And embrace change”.

SIMON ESPLEY is a proud African of the digital tribe and honoured to be CEO of Africa Geographic. His travels in Africa are searching for wilderness, real people with interesting stories and elusive birds. He lives in Hoedspruit, next to the Kruger National Park, with his wife Lizz and 2 Jack Russells. When not travelling or working, he is usually on his mountain bike somewhere out there. Simon qualified as a chartered accountant, but found his calling sharing Africa’s incredibleness with you. His motto is “Live for now, have fun, be good, tread lightly and respect others. And embrace change”.

A special thanks to MARIA DIEKMANN, founder and director of Pangolins International. Maria has been a surrogate mother to the star of this issue, Katiti, and has rehabilitated and returned many other pangolins to the wild. While balancing this with the work she does to rehabilitate other species, Maria has always been at hand to provide us with vital content to make this issue possible.

A special thanks to MARIA DIEKMANN, founder and director of Pangolins International. Maria has been a surrogate mother to the star of this issue, Katiti, and has rehabilitated and returned many other pangolins to the wild. While balancing this with the work she does to rehabilitate other species, Maria has always been at hand to provide us with vital content to make this issue possible.

CHRISTIAN BOIX left his native Spain, its great food, siestas and fiestas, to become an ornithologist at the University of Cape Town and a specialist bird guide. Time passed, his daughter became convinced he was some kind of pilot, and his wife acquired a budgie for company – that’s when the penny dropped. Thrilled to join the Africa Geographic team; Christian is their resident safari expert and guide.

CHRISTIAN BOIX left his native Spain, its great food, siestas and fiestas, to become an ornithologist at the University of Cape Town and a specialist bird guide. Time passed, his daughter became convinced he was some kind of pilot, and his wife acquired a budgie for company – that’s when the penny dropped. Thrilled to join the Africa Geographic team; Christian is their resident safari expert and guide.

JUDY & SCOTT HURD are photographers living and working in Namibia, a country they see as the most photogenic on the planet. They have accumulated a huge wildlife library, some of which you can view on their website.

JUDY & SCOTT HURD are photographers living and working in Namibia, a country they see as the most photogenic on the planet. They have accumulated a huge wildlife library, some of which you can view on their website.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()