The hunting season for many species in South Africa has just begun. This has prompted people interested in leopard conservation to make enquiries regarding the leopard hunting quota for SA for 2021 – a task that should be quite simple, given that the public is legally allowed access to this information. However, it has proven almost impossible to obtain any information regarding 2021 quotas, the science that advised the upping of quotas from 2018 to 2020 and for some areas, how many leopards were hunted in 2020.

Enquiries to the Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment (DFFE), the South African National Biodiversity Institute (SANBI) and the North West Province have been ignored completely. LEDET (Limpopo Province) was more forthcoming. In answer to a query as to whether any of the nine leopards allocated to this province for 2020 had been hunted, they responded that four were hunted. They also revealed that a 2021 leopard hunting quota for Limpopo Province had not yet been set. Therefore, I can only assume that quotas have not been set for any province in SA for 2021.

It seems that more openness, honesty, and a willingness to share information on this topic are sorely needed. If the DFFE were to provide clarity and less obfuscation regarding who the public should turn to for enquiries regarding permits, quotas and the latest population trends, they would instil more trust in those of us concerned with leopard conservation in South Africa.

Declining leopard numbers

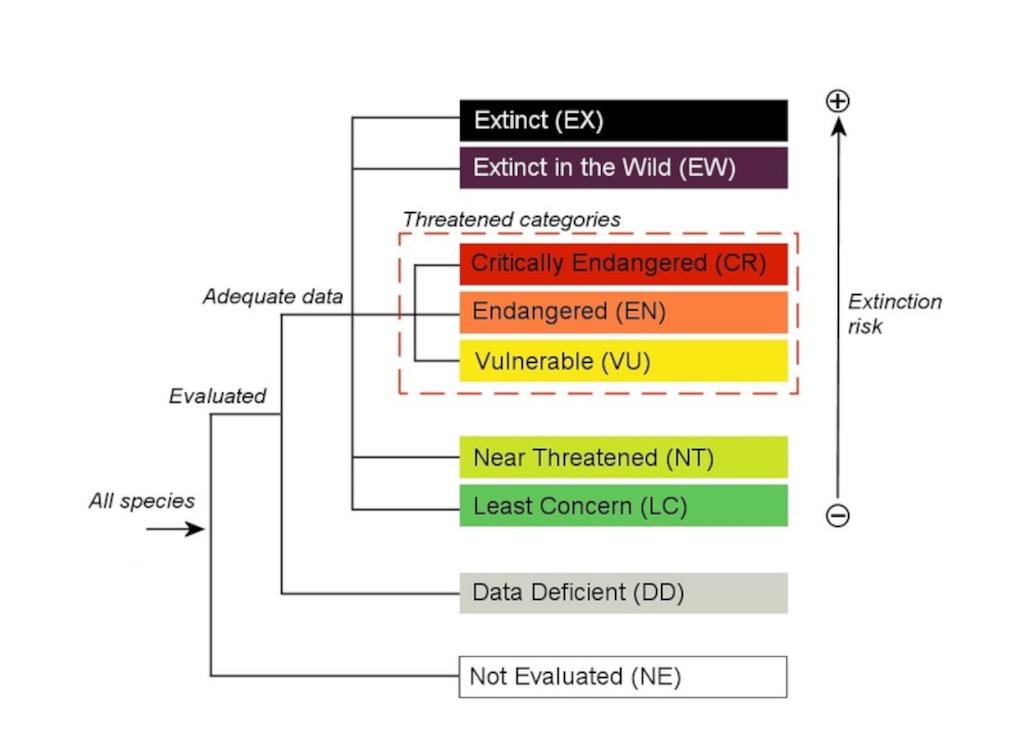

To understand the concerns regarding the current status of leopard conservation in South Africa, it is important to outline some recent history related to the species in this country. In 2002, leopards were listed as least concern on the IUCN Global Red List (Figure 1). Alarmingly, however, due to continuing decline in leopard populations globally and nationally1, this status changed to “Near Threatened” in 2008 and then “Vulnerable” in 20162. A study3 showed leopards to have disappeared from at least 37% of their historic African range. However, more recent studies1,4, paint a bleaker picture of an extensive leopard range reduction in the region of approximately 60%-70%1,4 with only 17% of the existing range protected and disturbingly, that leopards are extinct in 67% of South Africa4.

Improving leopard science

Before 2016, leopard hunting in South Africa was very poorly regulated. National population estimates to inform the CITES leopard quotas were based on outdated and meaningless studies20 that used rainfall and vegetation types to estimate population numbers and assumed that leopards occur at maximum population densities in all available habitats. These studies massively overinflated leopard numbers5. Credit needs to be given to the Scientific Authority (a group including scientists from SANBI, SANParks, one representative from each of the provincial conservation agencies and representatives from some NGOs such as Panthera and EWT). In the lead up to the hunting quotas being set in 2016, and against a massive backlash from the South African hunting community, the Scientific Authority fought for a zero hunting quota to be adopted by government. This allowed time to gain a comprehensive and more scientifically informed understanding of leopard populations across the country. Additionally, they wanted the opportunity to develop a framework for better regulated leopard hunting in SA. Thankfully, government took heed of the concerns raised, and the leopard hunting quota was set to zero for the years 2016 and 2017. This bought some time for scientists to collect the necessary data required for more informed decisions.

Undoubtedly, most scientists working to achieve these goals would have loved nothing more than to stop leopard hunting in the country altogether. Realistically, however, they understood the power and influence of the hunting lobby. They dealt with the pervasive threats by members of the hunting and game farming fraternity, who claimed that if they could not make money from the leopard on their land, they would simply shoot them and bury the evidence 21, 22. The scientists also acknowledged the contribution that hunting makes to conservation in terms of the land set aside for wildlife, which could easily be given to livestock farming, or worse, should hunting become unprofitable.

In a race against time, at huge expense and with the hunting community baying for blood, a concerted effort was made to set up an adaptive management framework for ethical hunting practices. This included establishing the South African Leopard Monitoring Project, a cooperative effort between the NGO Panthera, SANBI and other partners. Panthera had been monitoring leopard populations using camera trap surveys in parts of KwaZulu-Natal and Limpopo since 2013. SANBI provided additional funding to expand the project to other provinces in 2016. These surveys were intended to inform leopard conservation policy and provide a reference point to gauge the impact of future management decisions6.

Illogical quota increases

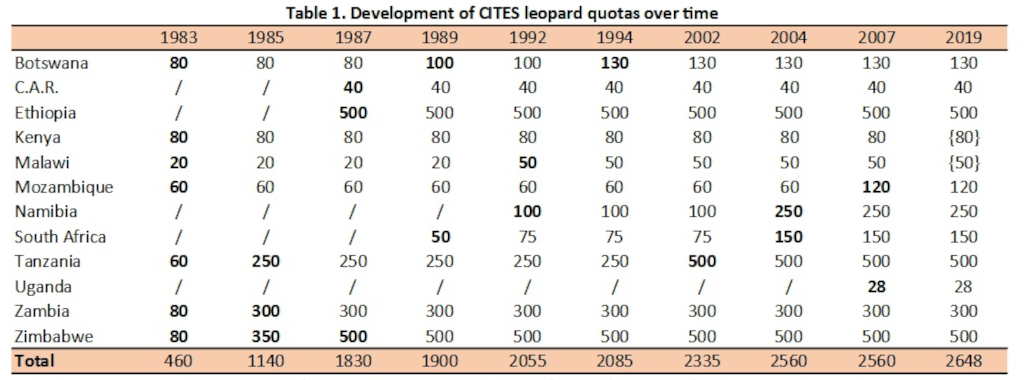

Shockingly, until the 2016 leopard quota review in South Africa, there were no restrictions on the size, age or sex of leopard that were legally hunted7. CITES allowed any leopard trophies to be exported as long as they were within quota and accompanied by the requisite permits. CITES, by the way, has a track record of bad decision making for leopards and other species. The existing quotas are unsustainably high5. It beggars belief that with global and regional red lists over the last 20 years showing a concerning decline in the status of leopard, the CITES quotas for leopard in all African range states has INCREASED or remained unchanged since 1983 (Table 1). Not a single reduction in CITES export quotas for leopard for African range states has occurred5.

The new SA management framework stipulated that only male leopards aged seven or above were allowed to be legally hunted in South Africa. Although this age has come under harsh criticism from many, (particularly because leopards are an infanticidal species, seven-year-old males are in the prime of their breeding lives, and hunters have proven very poor at ageing leopards)7, there is no doubt that it is a huge improvement on what was in place before. For more details on problems with the government’s proposed norms and standards for leopard hunting8, see the objection9 submitted to government in 2017 in the references.

A continued decline

The results of the South African Leopard Monitoring Project’s population survey for 2017 to 2018 suggested a concerning 11% per year decline of the leopard population in SA6. The monitoring was conducted in protected areas across the country. If these “protected” populations showed 11% declines, then it suggests non-protected areas, which form the bulk of South African leopard habitat (and where leopard hunting will take place), are experiencing far greater declines.

The survey report called for urgent action to combat the illegal trade in leopard body parts, which the authors saw as the biggest and most immediate threat to leopard in South Africa. In a devastating response to this report, the government, rather than implementing a plan to stop the illegal killing of leopard for traditional use, immediately set a leopard hunting quota of seven animals for 2018 and suggested that the CITES export quota of 150 leopard trophy’s stay the same. The hunting quota has since increased to 11(nine allocated to Limpopo Province and two to North West Province) in 2020, and Government has remained steadfastly quiet about its plans to deal with the traditional and cultural use of skins.

A note on the CITES quota of 150: In the years between 2005 and 2016, South Africa never fully used its export quota of 150 skins, but rather an average of about 70 per year. With hunting quotas set so low at the moment, it seems strange that the DFFE would have wanted to retain the high CITES quota unless they are planning on increasing hunting quotas quite dramatically over the next few years. By CITES own admission, exporting species at a level that is well below a CITES quota normally implies that the quota was set arbitrarily. Yet, our government asked for this obviously ridiculous quota to be retained. WHY?

Pointless research

Researchers have been rapped over the knuckles by scientists12, who found that most leopard research in South Africa had little relevance to the conservation of the species. Most studies were concentrated in areas of low conservation concern and focused on basic research, like feeding ecology in protected areas, rather than applied research relevant to the conservation of the species. Other findings 10,11 questioned the necessity of leopards being collared for research purposes. They drew attention to many studies submitted to the South African Journal for Wildlife Research that lacked ethical clearance or permitting approvals. Radio telemetry11 was found to be the most common method used to study leopard in South Africa, but the costs often outweighed its benefits, as collars frequently caused death or injury to the animals. They suggested that non-invasive methods like camera traps be used where possible and proposed a method to enable researchers to balance the welfare concerns of individual leopards with the urgent requirement for accurate data to inform conservation decisions. Organisations doing the most relevant research were found to be NGOs. Researchers urgently need to focus their attention on studies that will contribute to the conservation of the species by identifying the preeminent threats to leopards and designing research activity around those threats.

Why not consider metapopulation management of leopard?

Conservation scientists, government, ecotourism, NGOs, law enforcement and the game farming industry need to pull together to establish a Metapopulation Management Plan for leopard, similar to those in place for cheetah and African wild dog. Essentially a Metapopulation Management Plan, instead of managing leopard in each game reserve or area separately, treats the population in the country or sub-region as one large metapopulation. Animals can then be regularly moved from areas where populations are healthy and growing to areas where the species is locally extinct, or numbers are low15. A system like this allows managers to increase the genetic diversity of small fragmented groups of a species and creates opportunities to move problem animals to other areas instead of shooting them.

Like parts of the Drakensberg, some areas in our country have perfect leopard habitat but seem to have virtually no leopards, according to recent camera trap surveys6. Leopards that are earmarked for hunting could theoretically be used to repopulate these empty areas. This warrants consideration as a matter of urgency for leopard before, not after, the species becomes critically endangered. Perhaps metapopulation plans have not been put into place for leopard because the perception is that they are notoriously difficult to relocate, but recent research suggests that as long as certain conditions are met, leopards can and have been relocated successfully. 16, 17, 18, 19

Conclusion

In closing, there is no doubt that leopards are in trouble in South Africa – as confirmed by the above population surveys. Historically, the hunting fraternity, The SA Government, and CITES have all failed to protect them. The adaptive management plan put in place by the Scientific Authority, while far from perfect, is an attempt to rectify this. However, it is unacceptable that the government has not been more direct in tackling the cultural and traditional use of leopard body parts, rather relying on organisations like Panthera13 to run these programmes with little visible support from the DFFE.

The gauntlet has also been thrown down by some of the preeminent leopard specialists in the country, the ones who are providing quality research that is relevant to the conservation of the species. Conservation scientists and ecotourism businesses need to play their part in furthering our knowledge of the species in a relevant way to their conservation. This will enable us to improve on the adaptive management plan for the benefit of leopard conservation.

It is unacceptable that the public is not granted access to information on the latest leopard population trends and hunting quota information. It creates an atmosphere of secrecy, suspicion and distrust. Concerned South Africans need to be informed to ensure that our government doesn’t follow the example of CITES and keep putting quotas up when all evidence points to a population in dire straits.![]()

For further reading on South African leopard hunting quotas a look here, here, here and here

References

- Stein, A.B., Athreya, V., Gerngross, P., Balme, G., Henschel, P., Karanth, U., Miquelle, D., Rostro, S., Kamler, J.F. and Laguardia, A., 2016. Panthera pardus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e. T15954A50659089. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/308899520_Panthera_pardus_The_IUCN_Red_List_of_Threatened_Species_2016_e_T15954A50659089

- Swanepoel LH, Balme G, Williams S, Power RJ, Snyman A, Gaigher I, Senekal C, Martins Q, Child MF. 2016. A conservation assessment of Panthera pardus. In Child MF, Roxburgh L, Do Linh San E, Raimondo D, Davies-Mostert HT, editors. The Red List of Mammals of South Africa, Swaziland and Lesotho. South African National Biodiversity Institute and Endangered Wildlife Trust, South Africa. https://capeleopard.org.za/images/docs/publications/2016_Swanepoel_et_al_A_conservation_assessment_of_Panthera_pardus.pdf

- Ray, J. C., Hunter, L., & Zigouris, J. (2005). Setting conservation and research priorities for larger African carnivores. http://s3.amazonaws.com/WCSResources/file_20120403_095402_WCS_WorkingPaper_24_web_xWA.pdf

- Jacobson, A.P., Gerngross, P., Lemeris Jr, J.R., Schoonover, R.F., Anco, C., Breitenmoser-Würsten, C., Durant, S.M., Farhadinia, M.S., Henschel, P., Kamler, J.F. and Laguardia, A., 2016. Leopard (Panthera pardus) status, distribution, and the research efforts across its range. PeerJ, 4, p.e1974. https://peerj.com/articles/1974

- Trouwborst, A., Loveridge, A.J. and Macdonald, D.W., 2020. Spotty data: managing international leopard (Panthera pardus) trophy hunting quotas amidst uncertainty. Journal of Environmental Law, 32(2), pp.253-278. https://academic.oup.com/jel/article-pdf/32/2/253/33482581/eqz032.pdf

- Mann, G., Pitman, R., Broadfield, J., Taylor, J., Whittington-Jones, G., Rogan, M., Dubay, S., and Balme, G. (2018). South African Leopard Monitoring Project, Annual report for the South African National Biodiversity Institute.

- Balme, G. A., Hunter, L., & Braczkowski, A. R. (2012). Applicability of age-based hunting regulations for African leopards. PloS one, 7(4), e35209. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0035209

- DEA (2018) https://cites.org/sites/default/files/eng/com/ac/30/E-AC30-15-A3.pdf Downloaded on [1st June 2021]

- Gaines (2017) https://www.yumpu.com/en/embed/view/gN5xuiSJz2jv7pCD?fbclid=IwAR0pveIMt9tyuT9uq8rt74pzuaPB3I4PSpz34R0rZLuc3VBndJabqX55bO0 Downloaded on [1st June 2021]

- Hayward, M.W., Somers, M.J., Kerley, G.I., Perrin, M.R., Bester, M.N., Dalerum, F., San, E.D.L., Hoffman, L.C., Marshal, J.P., Mills, M.G. and Nel, J.A., 2012. Animal ethics and ecotourism. African Journal of Wildlife Research, 42(2). https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Fredrik_Dalerum/publication/233953253_Animal_ethics_and_ecotourism_editorial/links/00b4952550b8682ca4000000/Animal-ethics-and-ecotourism-editorial.pdf

- Balme, G., Dickerson, T., Fatterbert, J., Lindsay, P., Swanepoel, L., and Hunter, L., (unpublished manuscript) A decision framework for reconciling ethics, science and conservation in wildlife research.

- Balme, G.A., Lindsey, P.A., Swanepoel, L.H. and Hunter, L.T., 2014. Failure of research to address the rangewide conservation needs of large carnivores: leopards in South Africa as a case study. Conservation Letters, 7(1), pp.3-11. https://conbio.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdfdirect/10.1111/conl.12028

- Panthera (2021) https://www.panthera.org/furs-for-life Downloaded on [1st June 2021]

- IUCN 2021. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2021-1. https://www.iucnredlist.org Downloaded on [2 June 2021].

- Miller, S.M., Harper, C.K., Bloomer, P., Hofmeyr, J. and Funston, P.J., 2015. Fenced and fragmented: conservation value of managed metapopulations. PLoS One, 10(12), p.e0144605. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0144605

- Briers-Louw, W.D., Verschueren, S. and Leslie, A.J., 2019. Big cats return to Majete Wildlife Reserve, Malawi: evaluating reintroduction success. African Journal of Wildlife Research, 49(1), pp.34-50. https://bioone.org/journals/african-journal-of-wildlife-research/volume-49/issue-1/056.049.0034/Big-Cats-Return-to-Majete-Wildlife-Reserve-Malawi–Evaluating/10.3957/056.049.0034.ful

- Weise, F.J., Lemeris, J., Stratford, K.J., van Vuuren, R.J., Munro, S.J., Crawford, S.J., Marker, L.L. and Stein, A.B., 2015. A home away from home: insights from successful leopard (Panthera pardus) translocations. Biodiversity and conservation, 24(7), pp.1755-1774. https://www.academia.edu/download/61094290/Leopard_Translocation20191101-1919-10b5t5w.pdf

- Hayward, M.W., Adendorff, J., Moolman, L., Hayward, G.J. and Kerley, G.I., 2007. The successful reintroduction of leopard Panthera pardus to the Addo Elephant National Park. African Journal of Ecology, 45(1), p.103. https://www.ibs.bialowieza.pl/g2/pdf/1621.pdf

- Power, R.J., Venter, L., Botha, M.V. and Bartels, P., 2021. Repatriating leopards into novel landscapes of a South African province. Ecological Solutions and Evidence, 2(1), p.e12046. https://besjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/2688-8319.12046

- Martin, R.B. and De Meulenaer, T., 1988. Survey of the status of the leopard (Panthera pardus) in sub-Saharan Africa. Secretariat of the Convention on International Trade Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora.

- https://citizen.co.za/news/south-africa/1404951/leopards-under-the-gun/amp/

- https://www.kznhunters.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/CHASA-HLP-Submission.pdf (see page 9, section 6.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()