endemic primates & evolutionary oddities

![]()

Introduction

Some 135 million years ago, gradual yet enormous forces broke apart the supercontinent Gondwana, and a landmass comprising present-day Madagascar, India, Antarctica, and Australia drifted away from Africa. Approximately 47 million years later, Madagascar separated from India and drifted off the coast of Africa in the Indian Ocean. For the last 88 million years, life on Madagascar has been on its own, an island of evolutionary oddities that includes the family of lemurs.

The inevitable outcome of this geographic isolation is that 90% of the island’s fauna and flora are endemic, with phenomenal biodiversity that is quite literally worlds apart from anything else on the planet. The island is so large, and its environment so diverse, that some have even argued that it should be considered the world’s eighth continent. The island is home to over 300 recorded species of birds (60% of which are endemic) and 260 species of reptile, including two-thirds of the world’s chameleon species. Yet it is the primate species of Madagascar – the lemurs – that are the island’s real “flagship” species.

The IUCN currently recognises 107 species of lemurs, but their classification is an ongoing process that incorporates new knowledge and research regularly. The lemurs of Madagascar have evolved with the island, influencing plant life and filling every available niche to form an exceptionally diverse superfamily of diverse shapes and sizes. They have also generated significant interest in visiting Madagascar for a wildlife safari to observe lemurs.

Where did they come from?

Unravelling the history of Madagascar’s animal inhabitants has proved somewhat complicated for scientists because, despite numerous dinosaur fossils, there is almost no record from around 66 million years ago to about 26,000 years ago. However, based on a series of complex genetic studies, researchers infer that, rather than being present when Madagascar broke away, the ancestors of modern lemurs arrived sometime after Madagascar achieved geographic isolation, probably between 50 and 60 million years ago. Since then, the family has evolved into a wide variety of diverse primates whose closest relatives are bushbabies (galagos), lorises and pottos.

The most popular theory is that early lemurs existed due to “sweepstakes dispersal” – a chance event that allowed an animal species to cross a massive geological barrier, in this case, the Mozambique channel. At some point, the lemur ancestors (which likely would have been relatively small) found themselves adrift at sea on a raft of plant material, perhaps due to a severe tropical storm or flood. Recent evidence indicates that ocean currents at the time moved toward Madagascar, and the island itself would have been slightly closer to its current position, making the journey relatively easy for a small primate to survive, especially one that could have entered a state of torpor.

This particular theory is, however, far from universal, and it is the aye-aye (see below) that has caused some of the controversies, as jawbones found in Africa (from a species known as Plesiopithecus) bear a very close resemblance to aye-aye morphology.

Giants of history

Assuming the early lemurs arrived by raft, once they disembarked, they colonised their new home, breeding, adapting, and evolving into the many species seen today. The absence of mammalian competition enabled them to fill several open ecological niches, although Madagascar’s harsh climate shaped this evolution, resulting in several shared traits, such as seasonal fat storage and strict breeding seasons (in all but two species).

While their classification is as controversial as their history, the consensus is that there are now five extant families of lemur: the Cheirogaleidae (the dwarf and mouse lemurs), the Daubentoniidae (the aye-aye is the only living representative), Indriidae (which includes the indri, woolly lemurs and sifakas), Lemuridae (which includes the “true” lemurs, the ring-tailed lemur, the ruffed lemurs and bamboo lemurs), and Lepilemuridae (sportive lemurs). The largest of these is the indri, which can weigh up to 9.5kg, and the smallest is the critically endangered Madame Berthe’s mouse lemur, which weighs around 30g.

Astoundingly, however, just 2000 years ago, there were three other families of much larger lemur species: the Arcaeolemuridae (monkey lemurs), Megaladapidae (koala lemurs) and the enormous Palaeopropithecidae (sloth lemurs). The largest of all lemurs was a member of the sloth lemur family, a species known as Archaeoindris fontoynontii or “giant sloth lemur”, which probably reached a mass of 160kg and was roughly the size of a small gorilla. While there is no conclusive evidence for why these larger lemur species died out, their disappearance coincides with the arrival of the first humans on Madagascar.

All in favour say aye (aye)

By and large, lemur species are highly attractive, with thick, fluffy coats and striking colouration. The aye-aye could be considered the exception to this particular rule – it looks a little like a creature created by an overly-imaginative fantasy writer. Unfortunately for this entirely harmless and unassuming creature, its unusual appearance has inspired several supernatural and superstitious beliefs. The local myths around the aye-aye suggest that it is a harbinger of evil, occasionally sneaking into people’s houses to stab them in the neck with its absurdly long finger. The unfortunate result is that the aye-aye is often judiciously killed on sight, which may well account for the extinction of its cousin, the giant aye-aye.

In reality, the aye-aye is Madagascar’s woodpecker (no, really). The tiny third finger, which has a ball-and-socket joint, is used to tap on the bark of trees, and the aye-aye listens to the resonance to locate the insect life within. Once it has struck it lucky, the aye-aye nibbles away the bark and uses the extended fourth finger to fish out the insect larvae. A sixth digit has evolved as a pseudo thumb to help the aye-aye keep its balance while feeding. This oddball design, coupled with continually growing incisors, has made the classification of the aye-aye a contentious subject, but as technology has developed, it has become clear that aye-ayes are, in fact, the oldest of all living lemur species, the basal family. However, some biologists contend that aye-ayes colonised Madagascar independently of other lemur ancestors.

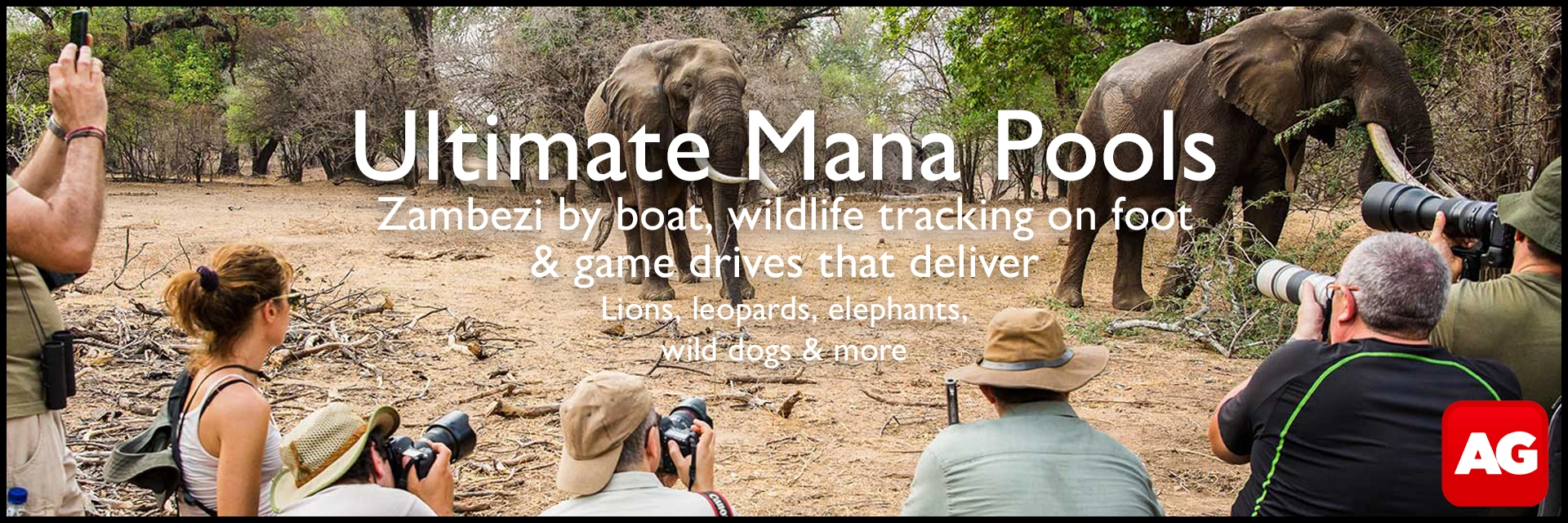

Find out about your safari to see lemurs in Madagascar. You can choose a ready-made safari or ask us to build one just for you.

Find out about your safari to see lemurs in Madagascar. You can choose a ready-made safari or ask us to build one just for you.

Other lemurs

Lemurs rival any other primate family in terms of diversity, and this diversity encompasses many different shapes, sizes, behaviours, dentitions, diets, and habitat use.

- Cheirogaleids: the dwarf and mouse lemurs, as their name suggests, are the smallest of all lemurs, and, in fact, the mouse lemurs are the smallest primates in the world. These tiny primates are nocturnal and arboreal, moving through the trees like bush babies. Their diet consists primarily of fruit and some insects. Available research suggests that these lemurs are typically solitary, although they have occasionally been observed in pairs. Members of this family can remain in a state of torpor for several months.

- Indriids: there are ten different medium- to large-sized lemur species belonging to the Indriidae family, with the woolly lemurs being the smallest and the indri being the largest of all lemur species. They are all arboreal, though some occasionally descend to move from tree to tree or forage. Sifakas, in particular, are known for their bipedal “dancing” when moving on the ground. Most species live in small groups that are predominantly female-dominated, and all species are almost entirely herbivorous.

- Lemurids: one of the largest families of medium-sized lemurs, this family includes the famous ring-tailed lemurs, “true” lemurs, ruffed lemurs, and bamboo lemurs. All are primarily herbivorous and highly arboreal.

- Lepilemurids: the sportive lemurs are strictly nocturnal, and most are solitary and territorial. Their hind legs are considerably longer than their front legs, making them ideally designed for leaping from tree to tree but restricting quadrupedal movement.

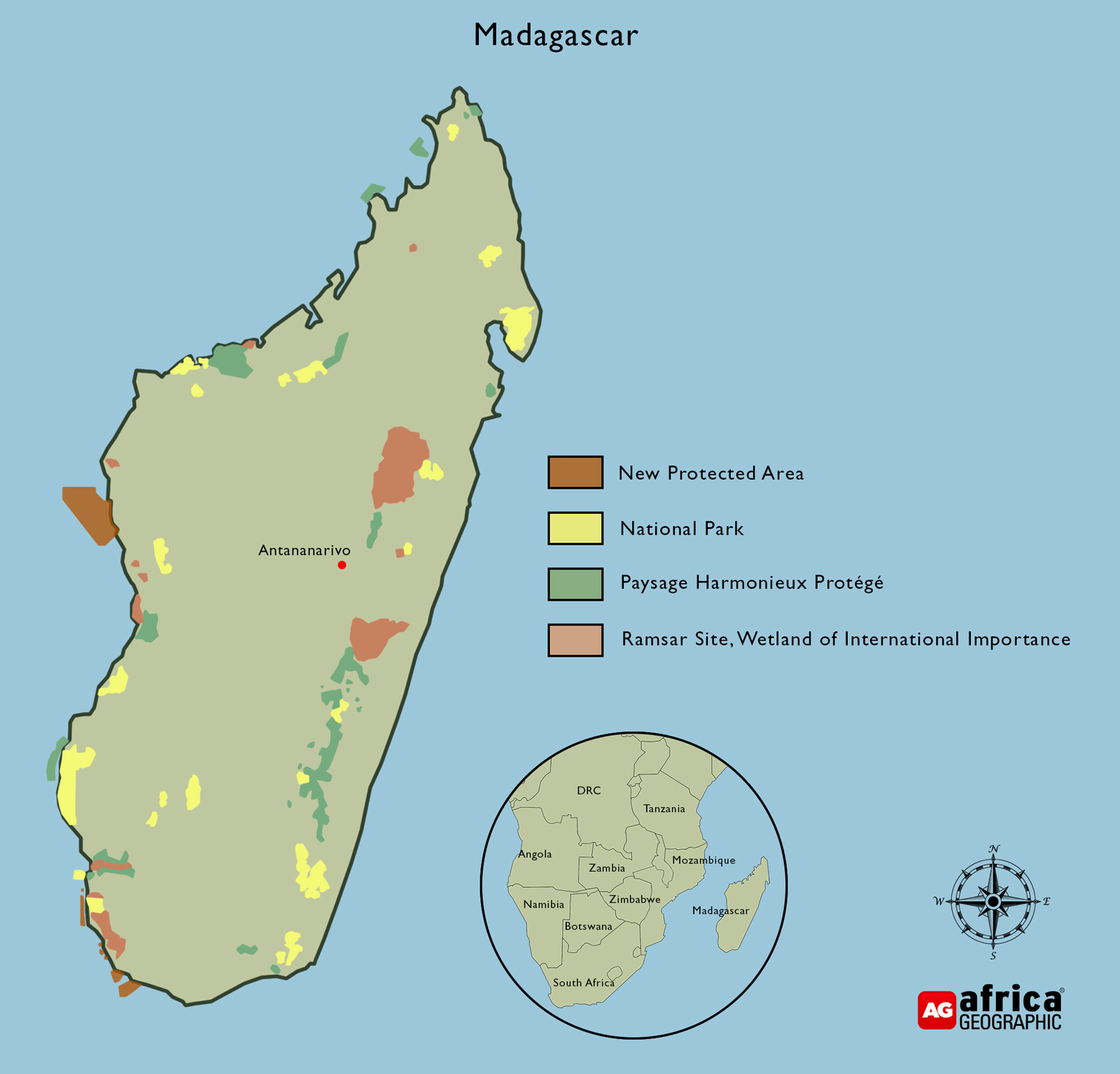

Conservation crisis

As fast as new lemur species are being described, their conservation status becomes more precarious. Some may even go extinct before scientists identify them as a separate species. Where once the lemurs were found throughout Madagascar, they are now believed to be restricted to less than 10% of their original distribution. Due to slash-and-burn agriculture and deforestation, lemur populations are now confined to highly fragmented, ever-shrinking forest patches (Madagascar has lost more than half of its forests in the last 60 years). This, coupled with bushmeat hunting and the illegal pet trade, makes lemurs one of the most at-risk animal families on the planet. In a recent announcement, the IUCN reported that 31% of lemur species in Madagascar are now listed as critically endangered, and 98% are threatened in some way.

Since the arrival of humans on Madagascar, all mammals over 10kg (including a pygmy hippopotamus species) have gone extinct, as have unknown numbers of bird and reptile species. Ring-tailed lemurs still give off a false alarm call for the long-extinct Malagasy crowned eagle, which once would have been one of their main predators. Despite extensive conservation efforts by dedicated individuals and organisations, Madagascar remains one of the poorest countries in the world, and only 3% of its land area is protected. Without severe and immediate intervention by the international community, it is a sobering reality that the haunting calls of lemurs echoing through Madagascar’s forests may be silenced forever.

Further reading

Bamboo lemurs on the brink, driven by climate change

Tiny primate: new species of mouse lemur discovered

New species of dwarf lemur discovered in Madagascar

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()