Tanzania’s wildest secret

Life in sub-Saharan Africa is ruled over by the cadence of the seasons. Nowhere in East Africa is the dichotomy between the dry and wet season more apparent than in Tanzania’s Katavi National Park. The arrival of the rains transforms landscapes, and a scarcity (or overabundance) can mean the difference between life and death. As the last thunderstorm dissipates beyond the horizon in Katavi, the park swelters beneath a merciless sun. Rivers slow to a trickle, honeycomb cracks appear in the mud, and the remaining water becomes a raw battleground. Hippos pack together in lingering wallows, crocodiles slither into sandbank caves, and herbivores must run the predator gauntlet as they line up to quench their thirst each day. For those in the know, this is what makes the remote Katavi one of the most electrifying safari destinations – a seldom-visited natural nirvana.

Katavi National Park

At 4,500km2 (450,000 hectares), Katavi is one of Tanzania’s largest national parks. It is situated not far from the country’s western border, just east of Lake Tanganyika in a truncated arm of the Great Rift Valley (the Rukwa Rift Basin) that ends around Lake Rukwa. The Lyamba Iya Mfipa and Mlele escarpments line the park to the west and east. The protected area is significantly augmented by surrounding game reserves, including Rukwa, Lukwati and Luafi (also spelt Lwafi) Game Reserves. Together with the national park, these reserves encompass some 12,000km2 (1,2 million hectares) of prime wilderness, stretching to the Ruaha ecosystem to the east and the chimpanzee forests of Mahale National Park to the north. Much of the park is dominated by miombo woodland interspersed by vast open clearings (including the 425km2 – 42,500 hectares – Katisunga Plain) and floodplains. Naturally, life revolves around the park’s rivers and reed-lined waterway networks. The Katuma River feeds the seasonal Katavi and Chada Lakes, its network supplemented by the Kavu and Kapapa Rivers. Ancient riverine forests dominated by tamarind trees line these river systems, providing ample shade for the elephants, buffalos and tourists that seek refuge beneath the canopy during the soporific heat of the day.

East Africa is, of course, a safari mecca and there are many places where wildlife viewing is simply extraordinary. Yet Katavi, on Tanzania’s southern circuit, stands out because it is so far off the traditional beaten safari track that it receives fewer than 500 visitors every year. Those visitors who make the journey are richly rewarded and often find themselves with a vast chunk of African savanna to themselves, without another tourist in sight.

Without the pressure of high tourist densities, the park authorities offer more freedom and activities to their adventurous patrons. Walking safaris are permitted in the company of an armed ranger, and self-drive visitors looking to camp in the park have innumerable options when picking a suitable site.

The park’s animals are less accustomed to people and vehicles. While far from skittish, they do not display the almost zoo-like disinterest in passing cars as seen in some more popular safari destinations. This, combined with Katavi’s remote and secluded ambience, gives the impression of a world where, for once, humankind is not entirely in control.

The Wild West

While Katavi’s far-flung and off-the-map quality is its most impressive drawcard, that is not to suggest that the wildlife sightings are not jaw-dropping in their own right. As already mentioned, Katavi truly comes into its own as a safari destination during the dry season. As the grass turns golden, the vanishing water turns the park into an extravaganza of nature at her most raw. This region boasts Tanzania’s highest densities of hippos and crocodiles – obviously species entirely dependent upon the presence of water. Yet, both have adapted to survive the annual disappearance of their preferred habitat for months at a time. Pods of hippos pack themselves into mud wallows by the hundreds, desperately seeking protection from the blazing sun. Social though hippos may be, hundreds of two-tonne animals crowded together are bound to cause the odd neighbourly feud and fights between bulls are especially common. During this spectacle, the resultant photographic opportunities are renowned for their bleak representation of nature’s savagery. Somewhat sensibly, the crocodiles prefer to avoid these Brobdingnagian mosh pits. Instead, they crowd into caves on the riverbanks, slithering over each other for a prime spot and entering a state of dormancy to wait out the dry season.

The more land-based creatures of Katavi are also forced to congregate around the drying water points, and the profusion of wildlife on display from May until October is an impressive sight. The Katavi region is known for its massive herds of buffaloes and numerous elephants, and hosts robust populations of lions, painted wolves (wild dogs), cheetahs, and hyenas. Elands gather in large herds in certain parts of the park, and fortunate visitors could be lucky enough to spot both roan and sable antelopes.

Over 400 bird species have been recorded. Naturally, most visitors are looking to take advantage of the mammal displays of the dry season, which does not equate with the best birding opportunities that Katavi offers. Instead, the best time for bird watching in the park is when the migrant species return to “summer” in Katavi from November until April, coinciding with the arrival of the rains. During these months, the seasonal lakes fill, and floodplains revert to boggy marshland, making the waterbird viewing exceptional.

Explore & Stay

Want to go on safari to Katavi? To find lodges, search for our ready-made packages or get in touch with our travel team to arrange your safari, scroll down to after this story.

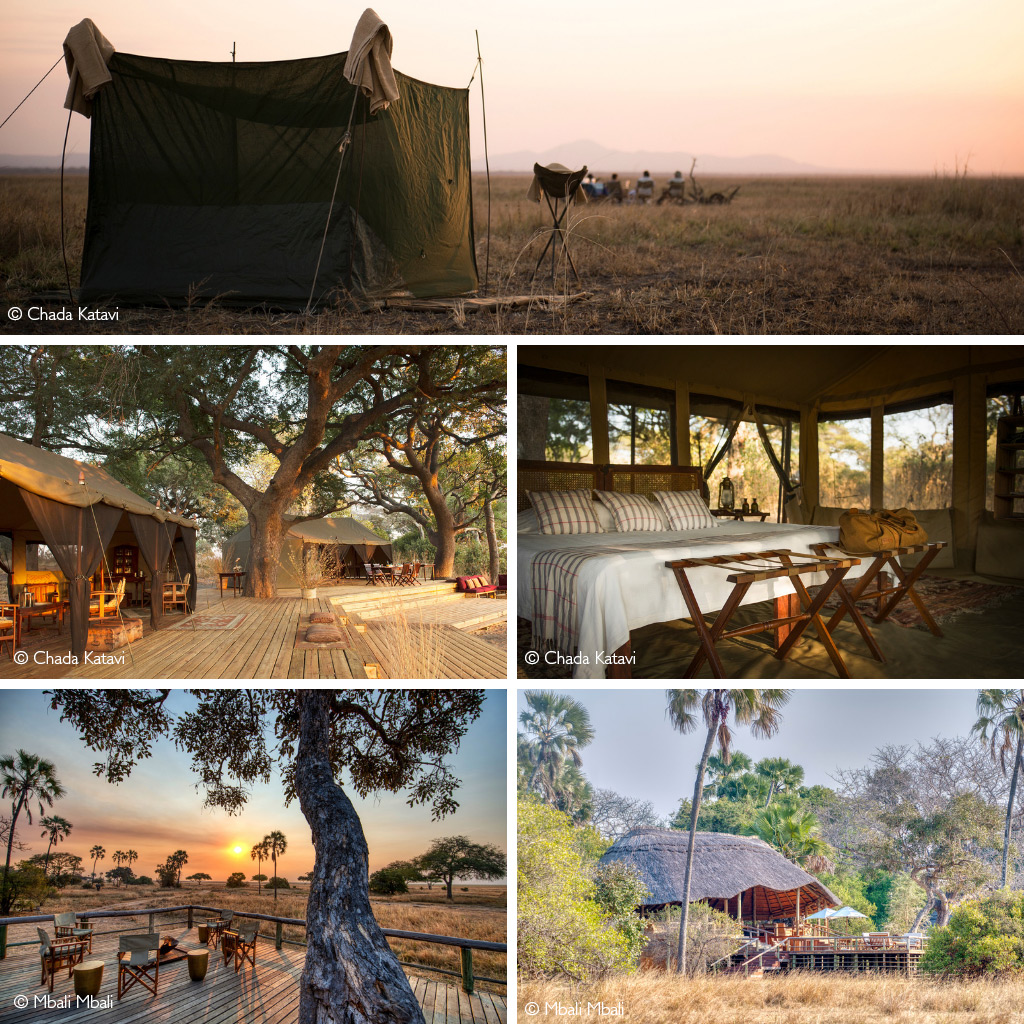

Though Katavi may be remote, the park and surrounds offer a small number of luxury lodges on par with grandeur and comfort found anywhere else in Africa. These beautiful camps are carefully positioned to take full advantage of the arid months, offering spectacular “armchair” wildlife viewing from the lodge decks between game drives. Unfortunately, most of the camps are closed for part of, if not all, of the rainy season from November until May, when the roads become sludgy, and parts of the park become totally inaccessible. For the more intrepid visitor, camping and self-drive through the park is an option, though it is essential to consider the journey to get there (measured in days rather than hours). Most visitors opt to fly into the Ikuu airstrip – a three-hour flight from Dar es Salaam.

Parting thoughts

In the heart of Katavi National Park, near Lake Katavi, an innocuous-looking tamarind tree holds a deep spiritual meaning. Here, the Bende and Pimbwe people believe that the spirit of Katabi – a great hunter – has taken up residence, and he looks out across the mountains where his wife, Wamweru, resides. Katavi was named for Katabi, the hunter-spirit, and it is believed that gifts and offerings placed at the base of the tree will bring good fortune and blessings. The local people are seemingly content to share the favours of Katabi, and visitors are encouraged to leave behind their gifts to the precious tree.

This gem of cultural history is just one part of what makes the Katavi experience so raw and intense – an awareness of both the power of nature and our intimate, intuitive connection to it. With her seasonal foibles and dramatic interplay of life and death, untrammelled Katavi is genuinely one of Tanzania’s best-kept secrets.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()