The perfect antelope

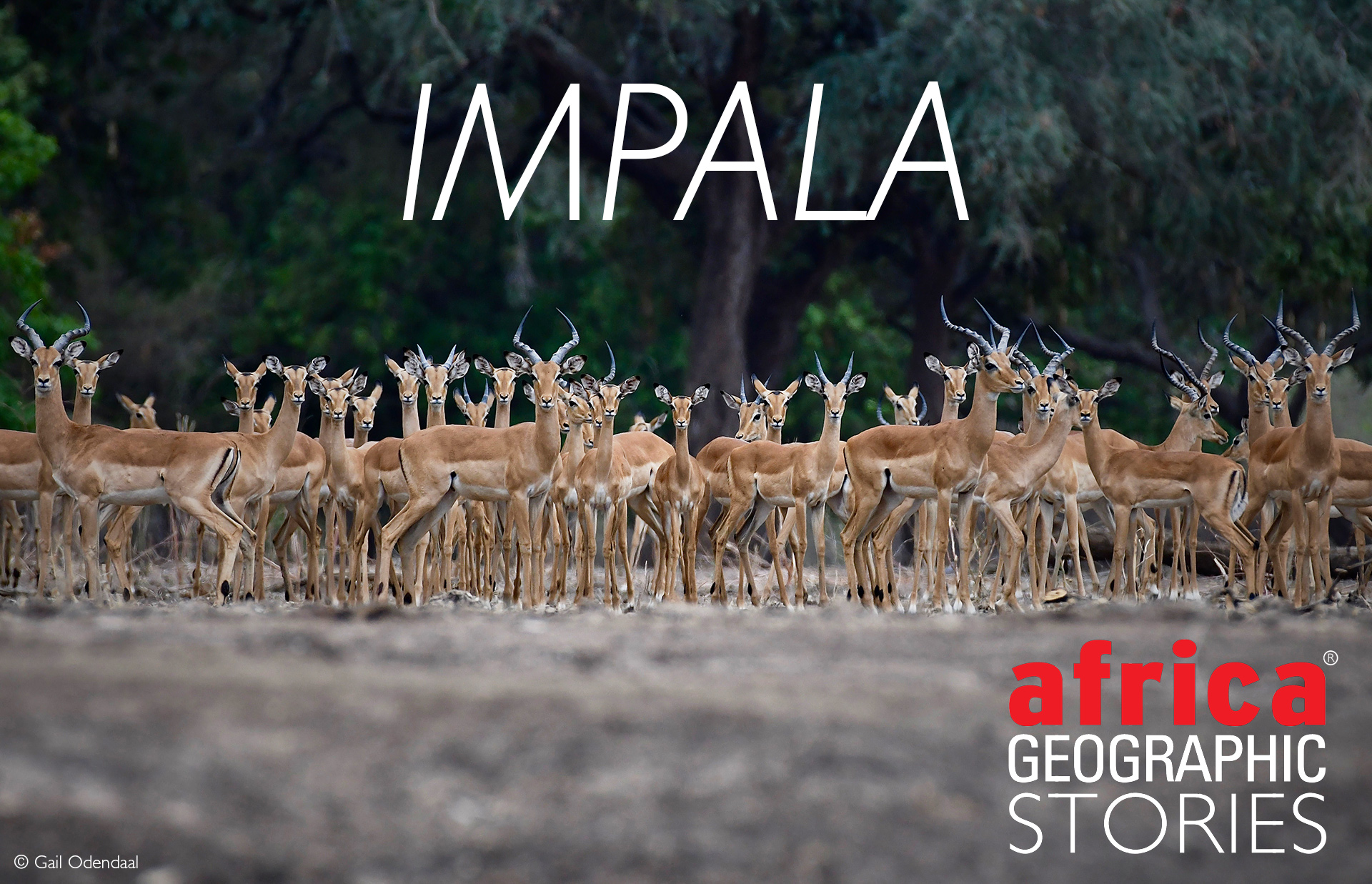

Ask any safari guide or returning guest about their favourite animal in Africa. The answer is invariably one of the more “charismatic” creatures – lions, leopards, giraffes, elephants and so on. The chances of their saying “impala” are small. Ubiquitous as impala are, these elegant antelope are generally overlooked by all but the most enthusiastic of nature lovers. Yet viewed through appreciative eyes, the impala is one of the most remarkable animals in the African bushveld: doe-eyed, resilient and effortlessly athletic.

Impala basics

In his seminal book on the behaviour of African mammals, celebrated ecologist Dr Richard Estes describes the impala (Aepyceros melampus) as “the perfect antelope”. Though he does not explain his reasons for this sentiment, it isn’t difficult to understand his thought process. Impalas are widespread and abundant throughout much of sub-Saharan Africa and are easily one of the most common antelope species. Moreover, the impala hit upon the perfect recipe early in its evolutionary history. Research shows they have remained relatively unchanged for at least five million years.

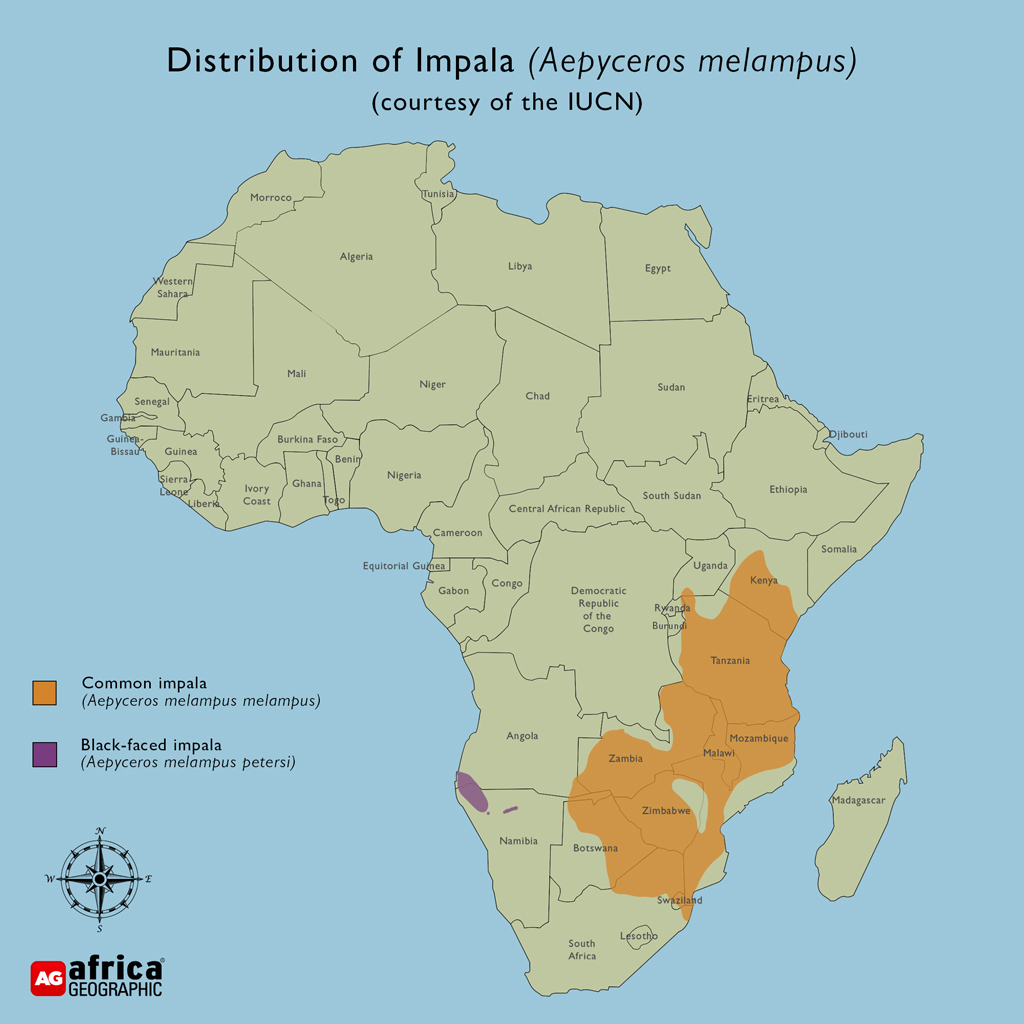

While previously believed to be a sister taxon to the hartebeest family, genetic studies have revealed that the impala’s closest relative is the diminutive suni (Neotragus moschatus). However, the impala is the only member of its genus and is the sole member of the Aepycerotini (“high horned”) tribe. Though there is only one recognised species of impala, the black-faced impala (A. m. petersi) of Namibia and Angola is listed as a valid subspecies on the IUCN Red List.

One explanation for their early evolutionary success is the impala’s unfussy approach to sustenance. They are mixed feeders, meaning they will graze, browse, and switch between feeding modes depending on the season. They focus on grasses during the early rainy season, when the grass species are green and still growing, before slowly switching to browsing foliage, shoots and forbs as the dry season progresses. This flexibility in feeding is also seen in different habitats. It confers an unusually abundant and reliable food supply and ensures that the impala ewes generally have sufficient sustenance to produce a lamb yearly.

An impressive production of new lambs each year is essential, as impalas are a staple prey species for all large predators (including martial eagles and other birds of prey). Mortalities are high year-round, but especially during lambing. Therefore, it is somewhat unsurprising that impalas are alert and observant antelope. Their keen eyes are usually the first to pick out the creeping outline of a stalking leopard or cheetah. If a predator is spotted, the herd will let out a cacophony of sharp barks – unless the predator is a pack of painted wolves, in which case the herd may scatter without so much as a sound. However, research has shown that impalas tend to adopt a “better safe than sorry” approach and may be so jumpy that they give off a false alarm call. Consequently, other animals take the warning vocalisations of impalas less seriously.

The males and females are sexually dimorphic – the rams are larger and sport an impressive set of lyre-shaped horns.

Quick impala facts

| Shoulder height: | Males: 75–92cm |

| Females: 70–85cm | |

| Mass: | Males: 53–76kg |

| Females: 40–53kg | |

| Social structure: | Variable depending on region and season. Mixed herds, bachelor groups and territorial males |

| Gestation: | 194–200 days (six and a half months) |

| Conservation status | Least Concern |

In leaps and bounds

The spring-loaded impalas are undoubtedly one of the most impressive athletes in the animal kingdom, capable of leaping over three metres into the air and covering ten metres in a single bound. They are also exceptionally fleet of foot, capable of reaching top speeds of over 90km/hour. When running from predators, a herd of impalas will explode into a series of spectacular leaps in every direction, cutting in front of each other or jumping over other individuals in a way that makes it more difficult for the attacker to select a target.

These impressive physical displays are poetry in motion and a pleasure to watch, but even the impala seem to enjoy their abilities at times. On cooler mornings, individuals break out into a unique jumping style where the hindlegs are thrown upwards into a “handstand” before rebounding and leaping upwards again. This rocking high jump is still not fully understood and seems infectious – once one goes, many others follow. While impossible to prove, anyone who has ever witnessed impalas bounding about like this would be hard-pressed to deny that they – adults and youngsters alike – seem to be having fun.

Colours, contours and cleanliness

The rufous two-tone coats of the impalas are another distinguishing feature, with the dark fawn-coloured top half contrasting with tan flanks and a white underbelly. This is theorised to be an example of countershading in nature, breaking the pattern of light and shade of a three-dimensional animal. The idea is that the darker dorsal colouration helps disguise ventral shadowing when lit from above and hides the shape of the impala from potential predators. The flank stripe may also visually amplify the vertical leaps of fleeing impalas, making them seem even more impressive and thus deter predators. Interesting but so far unexplained is the astonishing similarity in the colouration of the impalas and the gerenuk – two antelope with no close phylogenetic relationship.

The dark line markings on either side and through the middle of the impala’s tail are likely signalling devices, particularly during a chase. When impalas are running from a threat or displaying stotting (showing off) behaviour, the tail is also raised to expose the fluffy underside, which may help individuals stay together as a group. The black metatarsal glands on the back legs – found only on the impala – are also believed to serve a similar function by releasing pheromones during high stress.

Of all antelopes, impalas are perhaps the most meticulous about grooming. They are also one of the few that engage in both self- and allogrooming (where one individual grooms the other). The loose teeth of the front lower jaw form a functional toothcomb that helps to remove ectoparasites.

A roaring good time

Impala social structures and spatial arrangements vary depending on region and seasonality. In Southern Africa, impalas have a strict breeding season that begins during the dry season and lasts only about a month. This seasonality is governed by decreasing day length. During the rut, the males’ androgen levels increase dramatically, and the physiological effects manifest as a thickening of the neck and enlargement of the testicles. During this time, mature rams are territorial, defending their patch from interloping males and working overtime to keep females herded around them. The impalas of East Africa (which are much larger) often have a more extended breeding season that may last for most of the year. Here the rams usually dispense with territorial defence for only a few months over the dry season.

These territorial males become single-minded to the point of recklessness, barely stopping to eat, groom, sleep or watch for predators. They produce a loud roaring sound so unexpected from an antelope that more than one safari guest has mistaken it for the terrifying sound of a fearsome predator. These highly-strung rams are far from conflict-averse, and violent clashes and serious injuries are frequent. This constant activity takes a considerable toll on their physical health, and a male will often find themselves ousted by a fitter competitor. This is even more pronounced in East Africa, where the males have to try and maintain territories for longer.

Interestingly, this behaviour is also seen during the lambing season in Southern Africa, albeit less dramatically. There is a corresponding spike in androgen levels in the males, which is still not fully understood, though it is probably related to the pheromones of the females in late-stage pregnancy.

The lambs of spring (well, summer)

There is a prevalent misconception that female impalas can delay the birth of their lambs for up to a month in anticipation of the arrival of the rains. However, this is a physiological impossibility – a ewe cannot control her fetus’s growth, and labour is triggered when the lamb reaches its full size. The arrival of some lambs later in the season can easily be explained by a later conception time – either because the ewe came into oestrus late or the first oestrus did not result in conception. Poor nutrition may also slow the growth of the foetus slightly.

In Southern Africa, the lambs are born around November and early December (check them out on your next safari to Greater Kruger), during this region’s “baby season”. A couple of days after birth, the mother will lead her lamb back to the herd, where it will join a nursery with the other newborns. These nurseries may be guarded by a few ewes or even left to fend for themselves for hours each day. When it comes time for the ewe to feed her baby, both mother and offspring bleat frantically until they are reunited. Like all ungulates, the lambs are quick to find their feet, and the sight of them bouncing around and showing off on absurdly spindly legs is utterly beguiling. Play fighting is a common sight, and the male lambs begin butting heads long before their horns grow.

The lambs are weaned as early as four months old, with just enough time for the females to try and recover body condition before the rut begins. To put her life into perspective, an impala ewe is pregnant for over six months, lactating for another four, and then has about a month to herself before the rams start chasing her from pillar to post. She will then fall pregnant again and grow a 5kg lamb during the dry season when available food is at its least nutritious. And, as if this weren’t enough, she can still run at over 75km/hour to escape predators. This should give some idea of the evolutionary marvel that is the svelte impala.

Final thoughts on impala

The next time you happen to find yourself on safari, take a moment to stop with a herd of impalas and spend some time simply observing them. The impala is the one animal you are almost guaranteed to spot on every game drive, so why not take the opportunity to appreciate them?

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()