By Gail Thomson, with input from Lise Hanssen, director of Kwando Carnivore Project.

Originally published in Conservation Namibia.

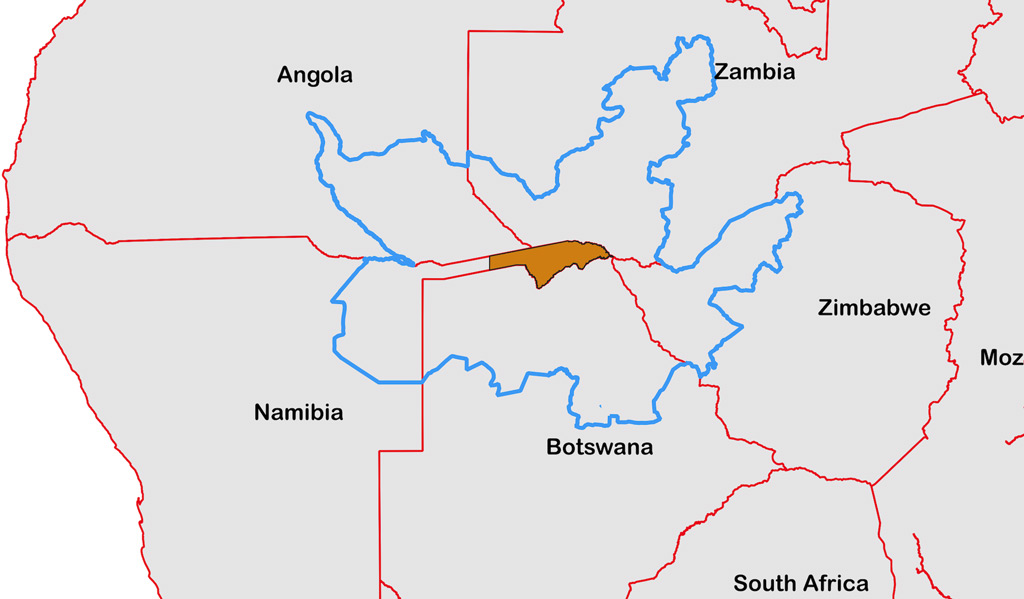

Human-lion conflict is a major issue for the conservation of wild lions. The Zambezi Region (formerly the Caprivi) is a small strip of land that fits like a Namibian key in a lock made of four other countries – Angola, Botswana, Zambia and Zimbabwe. This strip of land is near the centre of the Kavango-Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area (KAZA).

The KAZA landscape comprises fully protected National Parks, community conservation areas and mixed-use areas around towns and villages in all five countries. The Namibian component of KAZA has all of the same features of the broader landscape, only on a smaller scale. Most of the large carnivores and herbivores inhabiting this strip of Namibia don’t stay here their whole lives, or even for a year at a time. These animals move from country to country unencumbered by border controls that restrict human movements.

While small, the slender Zambezi Region (called the Zambezi here) is critical for conserving wildlife in KAZA – for a number of reasons.

- The Zambezi provides an important connection for animals moving north to south (e.g. Zambia to Botswana) or east to west (e.g. Zimbabwe to Angola) and vice versa;

- If wildlife populations decline in this area, it will create a “sink” or vacuum that will affect wildlife in all of the neighbouring countries;

- Lessons learned from conservation actions within the Zambezi, which is a microcosm of KAZA itself in many ways, can be useful for neighbouring countries.

Land use zones in the Zambezi Region are a heady mix of three National Parks, one State Forest, seven community forests, 15 communal conservancies (the community forests and conservancies often overlap), numerous villages and one major town – Katima Mulilo. With over 90,000 inhabitants in 2011, the Zambezi is one of the more densely populated parts of Namibia. Nearly 70% of the human population here is rural. While conservancies generate income from wildlife-based activities to spend mainly on community development projects, the average household relies heavily on farming activities like planting crops and raising livestock for their livelihood.

Into this milieu walks the lion; particularly the dispersing young male lion who is trying to find a pride in one of the five KAZA countries and pass his genes onto the next generation. Within a few days, a young male lion can move from Botswana to Zambia, walking right through Namibia. Young males tend to avoid the best lion habitat found in protected areas, because dominant pride males and their prides reside in these areas and will chase young interlopers out. This means they spend much of their time in farming areas and marginal habitats during their wandering adolescence. Then there are the established prides that spend most of their time in the National Parks, yet still make occasional forays into livestock farming areas nearby.

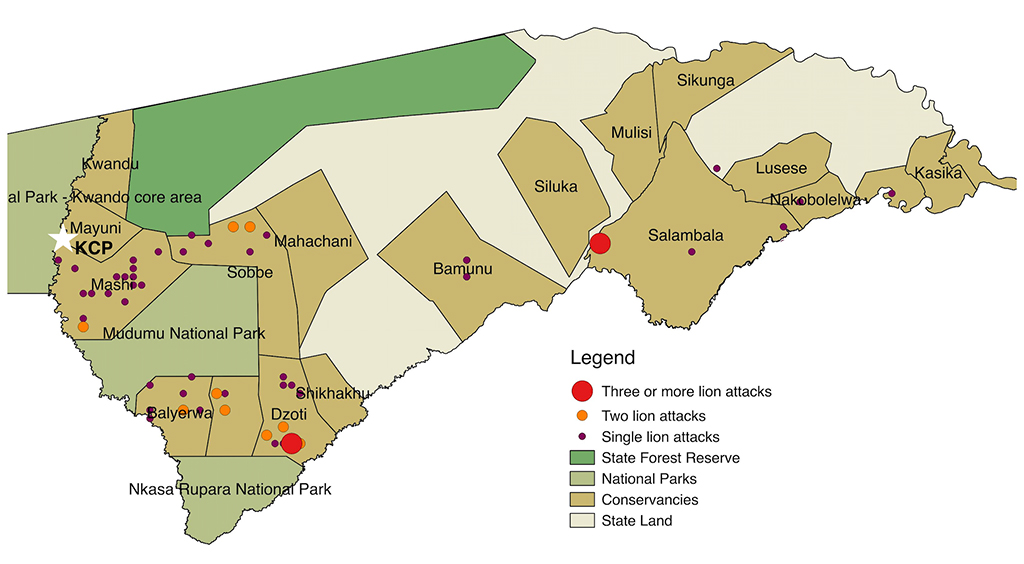

These movements inevitably bring conflict, as lions and cattle come into contact frequently and losses are suffered on both sides. According to conservancy Event Book records, 196 cattle were lost during 2012-14 leading local farmers to kill 20 lions in retaliation. One particular pride of 15 lions in 2012 had only three left by the end of 2014. Given the importance of this region within KAZA and the global importance of the KAZA lion population (one of the largest remaining strongholds for the species in Africa), the escalating human-lion conflict could not be left unchecked.

The Kwando Carnivore Project therefore established a human-lion conflict mitigation project in 2013, focusing initially on conservancies near Nkasa Rupara National Park (NP) that experienced the highest level of conflict. Given their initial success, they expanded their efforts to conservancies north of Mudumu NP in 2016. In 2017, they expanded yet again to include Namibian conservancies near the Chobe River floodplains lying to the north of Chobe NP in Botswana.

Given that lions usually attacked cattle at night while they were in makeshift traditional enclosures (“kraals”), the first order of business was to upgrade kraals in conflict hotspots to make them predator-proof. The conservancy Event Books were particularly useful in identifying where these hotspots were and the Project staff work closely with the conservancies to plan where to put kraals and then monitor the results. A total of 170 kraals have been upgraded to predator-proof status since the project began, resulting in cattle losses from kraals declining by 90% and lion killings being reduced from 20 in 2013/14 to one or two per year for the period 2015-19.

These are excellent results, but the work is far from over. Protecting cattle at night is just one part of the solution that needs to adapt with the lions’ response to cattle protection. If cattle are more difficult to prey on in one area that used to be a conflict hotspot, the lions may just move on to another area where the kraals have not been upgraded yet. If cattle are only protected at night and allowed to roam unattended during the day, then the lions adapt to target cattle during daylight. Lion behaviour changes with the seasons, as their natural prey gets easier (dry season) or harder (wet season) to find, thus making cattle more or less attractive for lions at different times of year.

The seasons also affect how people farm their livestock, which in turn affects losses to lions. Farmers allow their cattle to graze on harvested fields during the mid-dry season to help them survive until the rains come, often leaving them out there at night. Crop farmers in the Zambezi are especially busy during ploughing season, so they leave their cattle unattended more often in these times. Cattle on the Chobe floodplains are more vulnerable in the late dry season when the Chobe River almost dries up, thus allowing crocodile-free passage for lions coming from Chobe NP in Botswana. Finally, kraals that are filled with cattle dung become muddy havens for disease in the late wet season, so farmers prefer to let them roam outside to protect their health. All of these factors make cattle more vulnerable to attack by lions at certain times of year.

Due to the complexities of lion and human behaviour in response to climatic and ecological conditions, building predator-proof kraals is only part of the solution. While the project has reduced lion attacks on cattle, the issues of cattle not being brought into the kraal at night during certain times of year and not being herded during the day led to 67 cattle losses to lions during 2019.

In the coming year, the Kwando Carnivore Project will continue building kraals where they are needed but will add a few more tools to its conflict mitigation toolbox by collaborating with other conservation organisations. With Integrated Rural Development and Nature Conservation (IRDNC) and WWF-Namibia, they want to investigate employing “Lion Guards” to protect cattle during the day. Meanwhile, the Namibia Nature Foundation (NNF) and IRDNC have ideas for introducing conservation agriculture and better rangeland management practices.

Besides suffering fewer livestock losses to lions, it is important that people living with lions see a real benefit to their presence. In this way, a species currently seen as a liability can become a valued asset. The project thus assists with a Wildlife Credits scheme in Wuparo Conservancy that links lion sightings by guests at Nkasa Lupala Lodge to direct payments to the conservancy. These collaborative efforts will provide more holistic solutions to a complicated problem in a complex landscape.![]()

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()