The debate after we broke the story on the trophy hunting of two of Africa’s largest tuskers in Botswana has focussed on the ethical issues surrounding trophy hunting, and rightfully so. Should humans be permitted to kill animals for fun? And then there is the potential threat to big-tusker genes of selectively removing these giants from the breeding pool.

But for this post, I focus on three other issues that go to the core of trophy hunting, and hunting elephants, as a conservation tool:

1. FAIR VALUE

The trophy hunter paid at least US$80,000 for the ‘pleasure’ of killing this giant elephant*. Is this ‘fair value’ for one of a diminishing population of large-tusked elephants (tuskers)?

The questioning of fair value is essential. For example, what would the modern-day trophy hunter pay TODAY to kill a woolly mammoth – how many millions of USD? Because in 20 years, that will be a relevant comparison – these giant elephants are the woolly mammoth of today, and their slide into oblivion is surely a concern.

2. ADEQUATE COMPENSATION – RURAL COMMUNITIES

We have been advised that the Tcheku Community Trust, on whose land (NG13) this tusker was killed, was paid BWP200,000 (about US$16,285) for this elephant hunt – by a company called Old Man’s Pan Propriety Limited.

The company is owned by professional hunter Leon Kachelhoffer and Derek Brink – one of Botswana’s wealthiest men. So let’s be clear about this. Two wealthy individuals generate a massive 500% return on this giant elephant – and an entire community has to survive on the scraps.

Obviously I do not speak for this community (based in an area where protein sources are likely scarce) – who may appreciate an estimated minimum 600kg of elephant meat that such a hunt could produce. However, of concern is that our request to BWPA (see below) and Kachelhoffer for evidence – photos – that the meat was given to community members was refused. Also, suggesting that the supposed meat provision is a substitute for the cash they should have earned is insulting – the ultimate slap in the face for these desperate people. Do they know what this elephant was really worth?

The community trust’s total elephant allocation for the year is five elephants – all purchased in advance by Kachelhoffer and Brink. Seeing how little the community benefited from the killing of one of Africa’s largest tuskers, I would imagine that their revenue expectations for the remainder of the year are pretty grim.

This is nothing more and nothing less than the syphoning off of rural community wealth by hardened wealthy businessmen.

Is this the true face of Botswana’s much-acclaimed ‘sustainable’ trophy hunting strategy? In May 2019, Botswana’s President Masisi justified the decision to recommence trophy hunting by emphasising that local communities will be guaranteed far more than just menial jobs and will enjoy the economic benefits of sustainable wildlife management. I have no conceptual issue with controlled, sustainable hunting in areas where photo tourism fears to tread – because Africa’s people HAVE to be incentivised to have wild animals in their midst. Otherwise, we will end up like much of the ‘developed’ world – devoid of free-roaming wildlife. But is this how President Masisi envisaged involving impoverished, marginalised communities in the wildlife industry? Is this particular scenario fair to the good people of Botswana, or even sustainable – surely not!

3. MIGRATING ELEPHANTS

And what about the rural people in neighbouring countries – how do they benefit from this once-off event?

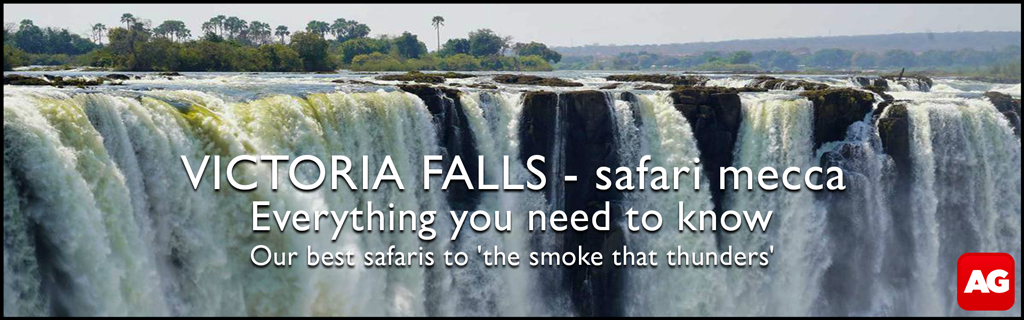

After all, this giant elephant was an international wanderer who would undoubtedly have paid his way via many photographic appearances over the years in the nearby (in roaming bull elephant terms) popular tourist areas of the Okavango Delta, Chobe, Caprivi, Victoria Falls and Hwange – to name a few.

On the topic of international elephant migration routes, we approached Nyambe Nyambe, executive director of Kavango Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area (KAZA), for feedback about trophy hunting elephants in elephant migration routes and the possibility of this creating ‘fear zones’ which hinder migration away from human-elephant conflict areas. One of KAZA’s aims is to enable elephant migration away from human-elephant conflict zones.

Nyambe pointed out that KAZA partner states consider trophy hunting a component of the wildlife economy. But he also said, “Partner States have imposed moratoriums on trophy hunting in particular areas of KAZA for purposes of rebuilding the populations alongside strengthening other conservation measures…”

Why then does Botswana create a new controlled trophy hunting area out of NG13 – which is slap bang in the elephant-migration corridor? On the face of it, this seems contrary to the underlying KAZA strategy to create safe migration corridors and alleviate human-elephant conflict.

Nyambe pointed out that KAZA cannot prevent partner states from going against the spirit of the partnership: “Any potential negative effects that could arise from efforts towards sustainable use (not just from hunting) will be duly investigated to mitigate any unplanned or negative impacts,” but KAZA does not take up issues with partner states, and rather relies on partner states to “engage with other or a particular partner state in the event of a concern.”

On the subject of fear zones, Nyambe suggested that my concerns are noted but probably overstated because trophy hunting does not occur across the entire wildlife dispersal area.

PARTING THOUGHTS

Botswana, and any other country, has the sovereign right to decide their own way forward when it comes to conservation issues such as these. And their focus on local people as beneficiaries of the wildlife industries is justified and necessary.

But surely Botswana can do better than this? Permitting a few privileged individuals to benefit at the expense of desperate rural communities is going to end badly – for Batswana and for their wildlife and ecosystems.

The trophy hunting industry seems incapable of self-regulation and has never been transparent about its dealings. Claims of sustainability are not backed by science and claims of significant benefits for local people are not supported by evidence. The authorities must step in and enforce better scientific rigour, transparency and accountability. They need to ensure a better distribution of wealth for Botswana’s rural people, better mitigation of human-wildlife conflict and a more sustainable offtake of genetically gifted animals that are now so popular as mantelpiece adornments.

* Notes

a) Three separate sources advised us that the minimum price for this sized elephant was US$80,000 to US$100,000

b) Our request to professional hunter Leon Kachelhoffer for information about the hunt proceeds, NG13 environmental management plan, license tender process and other specifics was initially met with assurances of cooperation, but he suspended discussions shortly after that. We were subsequently sent a letter by Kachelhoffer’s fellow Botswana Wildlife Producers Association committee members. The letter provided generic notes about elephant hunting and how the elephant was located in the vast NG13 but did not provide the requested information mentioned above. This lack of transparency is, unfortunately, par for the course. In a bitter, strongly worded follow-up letter, the BWPA advised us that they would not be responding to future requests for information.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()