by Rob Simmons, Colleen Seymour, Justin O’Riain

Cats touch all our lives in many ways… one may be curled up on your lap as you read this, providing you with invaluable comfort. Or they may be silently hunting through your neighbour’s garden, sight-unseen. Yet these cuddly, charming felids are honed killing machines whose impact on biodiversity in South Africa is only now being fully revealed.

Domestic and feral cats have been studied on every continent on the planet except Antarctica (where they don’t occur) and Africa (where they are more numerous than you probably realise). In fact, they may be the world’s most abundant and wide-spread carnivore, surviving on freezing sub-Antarctic islands to the hot, fire-ravaged deserts and forests of Australia.

On every continent, research has found that cats kill a wide diversity of wildlife, often in staggering numbers. For example, in the USA, a 2013 study estimated that domestic cats kill between 1.3–4.0 billion birds and 6.3–22.3 billion mammals annually. As we show below these are likely to be under-estimates for reasons uncovered in a study done in the south-eastern USA and confirmed in our own research programme here in Cape Town.

Our research investigated the impact that these ubiquitous agile predators have on the biodiversity around us. Three student projects (undertaken by Sharon George, Koebraa Peter and Frances Morling) explored the hunting habits of domestic cats in the spring, summer, and winter seasons across 22 Cape Town suburbs. Some of the cats lived in homes bordering Table Mountain National Park – so-called “urban-edge” cats, while others were more than 500m from the edge, termed “deep-urban” cats.

These studies found that cats in Cape Town suburbs occur at average densities between about 150 and 300 cats per square kilometre. This is on the low side compared to many countries, but similar to those found in Australia and New Zealand. However, these densities are more than 300 times that of their wild felid counterparts (e.g. Caracal (Caracal caracal) and African Wild Cat (Felis silvestris lybica), and this implies they may be having a rather large impact on wildlife around us.

To understand predation rates, we used the global protocol of asking cat-owners to serve as citizen data collectors – and they responded wonderfully, systematically recording prey returned home over 6 to 10 weeks. Cat owners also bagged prey for later identification.

In our sample of over 130 cats ranging in age from 6 months to 18 years old, we were surprised at just how many cats seldom returned prey home. What if, the students asked, the cats were eating or abandoning prey as they caught it? So, we turned to some nifty technology in the form of lightweight video cameras, dubbed “KittyCams” (a kind of “GoPro” for moggies), that the cats wore on break-away collars.

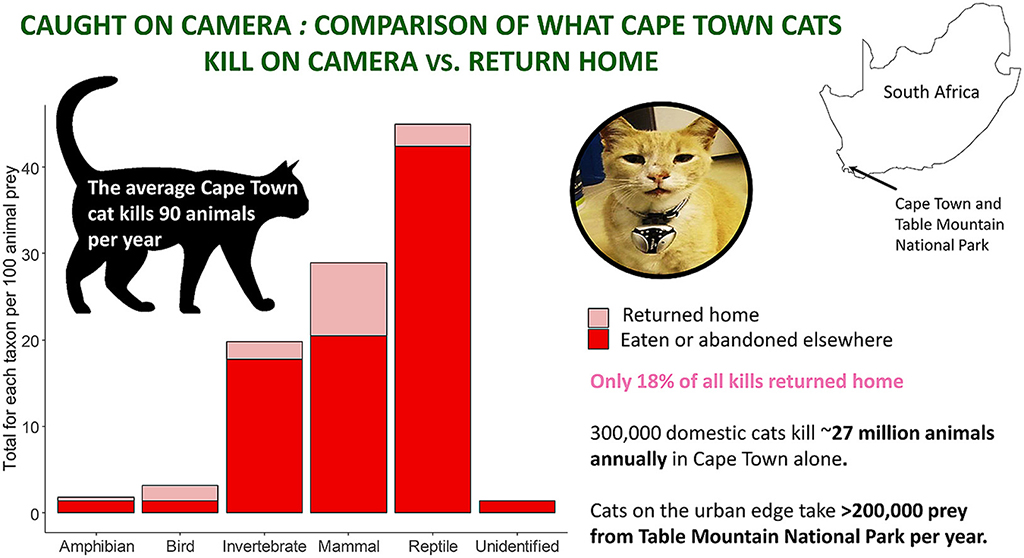

Cat owners’ records of prey returned home indicated that Cape Town’s cats killed an average of 16 prey per year, most of which were mammals. But those numbers all changed when the startling footage from the KittyCams came in.

Based initially in Newlands and then expanded to eight other suburbs, we first tested whether KittyCams affected the cats’ hunting behaviour, by comparing the number of prey returned by individuals with and without KittyCams. There was no difference.

The night-vision KittyCam showed that cats killed over 90% of their prey at night and over 80% of it was eaten on the spot or abandoned in the field. That meant that prey returns to the home were seriously under-estimating cat predation rates over five-fold.

The only other study using KittyCams in the USA found a similar under-estimation of 4.5-fold. The underestimation was not the only bias. Cats preferred to bring home birds or mammals they caught, but often ate or abandoned reptiles, amphibians, and insects where they caught them.

These biases have two implications. First, it explains why predation estimates from Cape Town cats and cats in other countries are likely to be under-estimates because to date, most studies have relied on questionnaire surveys of prey returns. Such studies would have to be multiplied by 4.5 to 5.6 to reflect the actual numbers of wildlife taken annually. As such, the average Cape Town cat’s annual impact is revised from 16 to 90 prey per year.

Since there are at least 300 000 domestic cats in Cape Town, the total kill rate is about 27.5 million animals per year. About 14 million of those are estimated to be reptiles, and a particularly favoured prey is the Marbled Leaf-toed Gecko, which is caught and consumed in seconds, and seldom returned home. For the bird lover, it is sobering to know that “only” about 450 000 birds are taken by Cape Town’s cats every year.

The second implication of this KittyCam study and the one conducted in the south-eastern USA is that until now, mammals and birds headed the lists on domestic cat predation to date because cats have more of a predilection for bringing these animals home. Our study shows that cats do indeed kill more mammals and birds than previously thought, but they are killing far more reptiles, amphibians and invertebrates than has ever been realised.

Of conservation concern is that at least 2200 cats live within 150 m of the edge of Table Mountain National Park, consuming an estimated 200 000 prey many of which are likely to be taken from within the Park itself or have wandered into gardens bordering the Park.

Of equal concern is that, if there are 2.4 million domestic cats as estimated by the pet food industry in South Africa, then at the rates computed for Cape Town’s cats we estimate that 216 million prey are likely to be taken across South Africa every year. This does not include feral cats which require a study all on their own.

Conservation authorities such as the South African National Parks (SANParks) have responded positively to the study, acknowledging the negative impacts of domestic cats on fauna in the Park and looking into the potential for buffer zones that might reduce these impacts.

We suggest that cat owners can help reduce the negative impacts of their pets with two simple interventions: (i) keep them in at night when predation peaks and the risk to cats of being run over by vehicles is highest and (ii) add bells to their collars which may reduce hunting success in catching birds and mammals, although this will not reduce impacts on reptiles (reptiles don’t hear the bells). Cats may, of course, switch their behaviour to hunting during the day, but that is research for another day. We stress that these will not stop predation, only reduce it, so longer-term measures are critical.

Concerned owners can consider catios, (enclosed patios) that allow a cat access into the garden but not further afield. They are already in use in North America as are lightweight (neoprene) bibs, that impede pouncing, but don’t impede the cat from drinking and eating. Both are effective in reducing predation.

An intervention to be explored with Table Mountain National park is the establishment of a stewardship programme for citizens whose properties border the Park. Having porcupines, Verreaux’s Eagles, spotted eagle owls, mongooses, genets and sugarbirds as neighbours comes with the responsibility to limit adverse urban effects such as pesticides, herbicides, invasive plants and exotic animals. A buffer of ‘biodiversity stewards’ would be a boon to the biodiversity of this World Heritage site and living in the ‘green zone’ a badge of honour in the fight against the global loss of biodiversity.

A montage of the kittycam footage captured by Frances Morling during one year of our study can be seen here:

A graphic of the main results of our study as it appeared in the published paper

Colleen Seymour, is a Principal Scientist with the South African National Biodiversity Institute, and a Research Associate of the University of Cape Town

Justin O’Riain is Professor and Head of the Institute of Communities and Wildlife in Africa (iCWILD) at the University of Cape Town

The original paper is accessible here: “Caught on camera: The impacts of urban domestic cats on wild prey in an African city and neighbouring protected areas”, Seymour, C., Simmons, R., Morling, F., George, S., Peters, K., O’Riain, J., (2020), Global Ecology and Conservation![]()

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()