- AI photo identification system – GiraffeSpotter – is turning giraffe images into verified population records.

- More than 30,000 individuals from 195,000 sightings now map giraffes across 18 countries.

- The new Giraffe Africa Database centralises data, improving comparability and reducing outdated estimates.

- All four giraffe species are stable or increasing, but trends vary regionally.

- Despite the good new, threats persist: habitat loss, poaching, insecurity, and under-surveyed areas still limit decisions.

Giraffes are no longer defined only by decline. Across Africa, all four recognised giraffe species are stable or increasing – a turnaround driven not by wishful thinking, but by sharper counting, wider coverage, and a far more disciplined approach to turning sightings into usable population data. And so it appears the future of giraffe conservation is digital.

The most consequential change is not a single new protected area or a once-off survey. It’s a monitoring system that turns photographs into structured, verified population intelligence, fast enough to matter, and rigorous enough to trust.

From snapshots to certainty

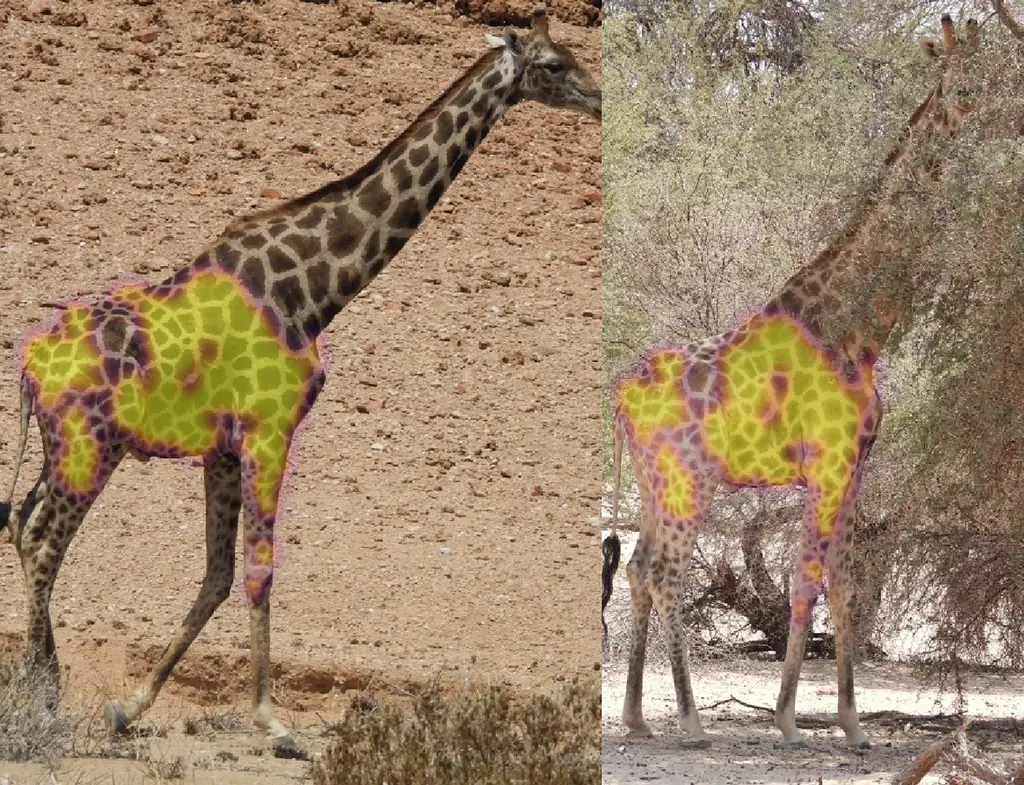

At the heart of this change is AI-powered photo-identification: GiraffeSpotter, an online photo-identification database managed by the Giraffe Conservation Foundation (GCF), is converting ordinary images into verified records of individual giraffes at scale. This gives conservationists faster access to better information, and a clearer basis for decisions that determine where giraffes will persist, and where they will not. GiraffeSpotter is one of several Wildbooks, open-source software platforms created by the Wild Me Lab of Conservation X Labs. These blend structured wildlife research with artificial intelligence, citizen science, and computer vision to speed population analysis and develop new insights in conservation based on traditional mark recapture survey methods.

Want to see giraffes on an African safari? Check out our safari ideas here, or let our travel experts plan the perfect African safari for you by clicking here.

Want to see giraffes on an African safari? Check out our safari ideas here, or let our travel experts plan the perfect African safari for you by clicking here.

As with most species, the core problem for giraffe conservation was simple: if you cannot reliably count a wide-ranging species across vast, mixed-ownership landscapes, you cannot confidently say whether protection is working, where numbers are collapsing, or where to intervene next.

Every single giraffe can be identified by their individual spot pattern – just like a human fingerprint. That means conservationists aren’t just collecting “giraffe sightings”. They’re building a living ledger of which individuals were seen, where, when, and how often – the kind of detail that turns management from guesswork into strategy.

How AI monitoring is driving giraffe conservation

AI monitoring, in this context, means using computer vision to identify individual giraffes from images, then using those verified identifications to build a live record of where individuals occur, how often they are seen, and what that implies for populations over time.

The database in GiraffeSpotter allows for the cataloguing and tracking of individual giraffes in the wild. Conservationists, researchers, and managers populate and maintain the database by collecting and analysing giraffe sighting data to understand population numbers and distribution.

The bigger picture is accountability. Traditional survey methods remain essential, but a photo-identification system offers another route: more frequent inputs and transparent records.

The database has identified more than 30,000 individual giraffes from over 195,000 sightings in 18 African countries, including populations of all four giraffe species. This makes it “the largest giraffe monitoring programme in history”.

The system allows governments, NGOs, academics, and local communities to track population trends and demographics in near real time, and use the information to design wildlife corridors, and even plan translocations with far greater confidence than ever before. A single system improves comparability, reduces the risk of double-counting, and prevents outdated estimates from being recycled unchallenged.

Importantly, GiraffeSpotter ensures that all data collected directly informs conservation strategies across Africa. By taking on the responsibility of verifying all data and ensuring high scientific standards, GCF guarantees that the information collected is not only scientifically rigorous but also applied immediately to inform conservation priorities.

The data backbone: the Giraffe Africa Database

GiraffeSpotter sits within a broader push to centralise and standardise giraffe status information. A key development is the launch of GCF’s Giraffe Africa Database, a single repository for storing and dynamically collating population data for all four giraffe species across the continent.

Giraffe data is often fragmented across government counts, NGO surveys, academic studies, private reserve monitoring, and local reporting. But this single system improves comparability and reduces the risk of double-counting or outdated estimates being carried forward unchallenged.

What the giraffe numbers currently show

With improved monitoring and more frequent giraffe-specific survey efforts, current estimates for wild giraffe populations are: Masai giraffe (43,926), Northern giraffe (7,037), Reticulated giraffe (20,901), and Southern giraffe (68,837).

The findings feed directly into GCF’s comprehensive State of Giraffe 2025 report, which for the first time reports stable or upward trends for all four giraffe species.

A crucial background point is what “stable” means in this analysis: when comparing changes from previous estimates, a population is considered stable if the estimate changed by ≤10%.

Why better monitoring changes the story

Improved monitoring can reveal real recovery, but it can also reveal that older methods were missing animals. As affirmed in the State of Giraffe 2025 report, aerial surveys “consistently underestimate populations”, and confidence in estimates depends strongly on method and recency.

To manage this, GCF uses an Information Quality Index (IQI) that ranks data reliability “from 1 (highest quality) to 5 (lowest quality)”, and the selection process prioritises data quality, spatial scale, and recency. It also notes that some populations have all individuals known and monitored in platforms such as GiraffeSpotter, linking photo-identification to the highest-confidence end of monitoring.

What the future holds

The initial development and implementation of park, national and regional giraffe conservation strategies and action plans in more than half of giraffe range states has been critical, according to the report. Evidence suggests that countries with these frameworks are seeing better conservation outcomes. GCF and its partners continue to support range states in developing and implementing these strategies and plans.

But the constraints remain serious and uneven. Ongoing threats such as habitat loss and fragmentation, poaching, climate change, and insufficient data remain challenges. Prioritising support for under-surveyed regions will be essential to sustain conservation gains. For example, limited systematic surveys were conducted on Masai giraffe in the past five years, resulting in a significant data gap in Tanzania. Reticulated giraffe numbers are increasing in Kenya, but there is little reliable data from neighbouring Ethiopia and Somalia because regional insecurity limits monitoring. Where monitoring cannot be done, conservation decisions become less precise and less defensible.

The bottom line

AI-assisted photo-identification is not a replacement for field conservation. It is a force multiplier for knowing what is happening, where, and how quickly. The intended chain from technology to action is captured in one line: “GiraffeSpotter is transforming snapshots into datasets, and datasets into conservation decisions.”

The future for giraffes depends on whether improved monitoring continues to expand into under-surveyed areas, whether shared databases remain current and comparable, and whether the threats that persist on the ground are met with plans that are resourced, enforced, and adapted as the data improves.

Reference

Marneweck CJ, Brown MB, Ekandjo P, Fennessy S, Hoffman R, Kipchumba A, Muneza A, Otten F & Fennessy J (Eds). 2025. State of Giraffe 2025: An update from the Giraffe Africa Database (GAD). Giraffe Conservation Foundation, Windhoek, Namibia.

Further reading

- Why do giraffes have such long legs? Giraffes’ long legs ease heart strain from high blood pressure, revealing an energy-saving secret behind their towering height. Read more here

- IUCN confirms four giraffe species, reshaping conservation across Africa and unlocking urgent, species-specific protection strategies. Read more here

- The giraffe is a wonder of evolution, and a vital part of Africa’s ecosystems. Read all there is to know about the planet’s tallest creature here

- Why do giraffes have such long necks? Various studies question whether feeding or mating played the bigger role in giraffe neck evolution. Read about Doug Cavener’s exploration into the driving force behind giraffe-neck evolution here, and Rob Simmons exploration into giraffe evolution’s tallest debate

- Under pressure – genetic research on giraffes reveals evolutionary secrets of how they cope with high blood pressure and maintain bone density. Read about the pieces of the giraffe evolution puzzle here

- Do giraffes choose their social groups based on appearance? A recent study investigates whether giraffes form bonds based on spot shape

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()