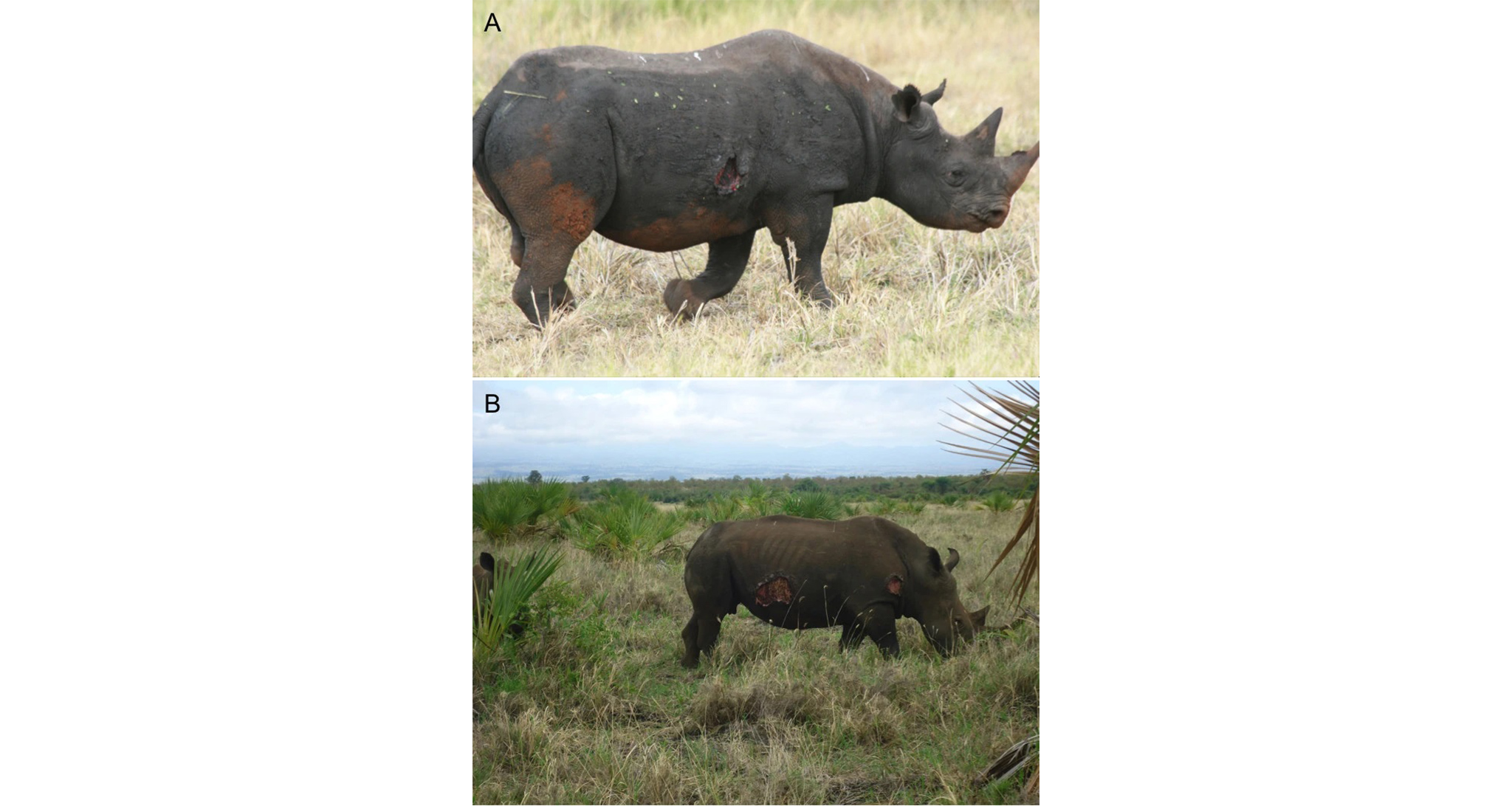

Every year, park authorities of protected spaces across much of Southern and East Africa deal with reports of injured black rhinos from well-meaning and concerned members of the public. In some cases, the injury is a genuine cause for concern. However, most cases involve something else entirely – a nasty, raw-looking, but generally harmless skin lesion. The culprit? A microscopic filarial worm.

Stephanofilaria dinniki belongs to the Filarioidea, a superfamily of parasitic nematodes (roundworms). These highly specialised parasites are spread by blood-feeding insects such as flies and mosquitoes, and many different species can infect people and domestic and wild animals. Infection by these filarial worms is known as filariasis and, if they invade the skin, causes severe dermatitis (inflammation of the skin) and severe itching. In people, they cause elephantiasis – massive swelling and thickening skin.

The open and weeping sores commonly observed on black rhinos (particularly in summer) were a subject of considerable speculation amongst experts for decades. For a long time, the dominant theory was that it was associated with the seasonal activity of secondary sex skin glands. However, in 1960 South African veterinarians and pathologists were finally able to isolate the cause. They collected several tissue samples from the ulcers and found the characteristic serpentine coils of nematodes in the superficial lymphatic vessels and tissue spaces. The surrounding cells – plasma cells and eosinophils (white blood cells) – were a testament to the host’s attempt to mount an immune response to remove the unwanted lodgers.

The infestations follow typical phases defined by the somewhat complex life cycle of the nematode. Larval nematodes (termed microfilariae) dominate when the wounds are most florid (red and raw). In the more chronic phases, the mature female Stephanofilaria dinniki burrow close to the surface, with uterine tubes filled with larvae. The inflammatory defensive response of the host’s immune system, followed by healing attempts, results in a fragile and highly vascularised granulation (pre-scar tissue) that bleeds very easily. This is why the wounds are often seen bleeding – even the lightest brush against a tree or rubbing post can damage the tissue. Eventually, the lesions become dormant, but often the damage causes scarring and thickening of the epidermis.

Though the life cycle of Stephanofilaria dinniki has not been conclusively researched, other members of the Filarioidea require an intermediate host, which could explain the seasonal pattern of the sores seen on black rhinos. Newly birthed microfilariae are not fully developed and need to mature in a blood-feeding insect before becoming infective and invading the next definitive host. As flies, mosquitoes and adult ticks are more abundant in the wet summer months, it makes sense that the wounds would be at their worst stage when the microfilariae are more likely to be spread. The open abrasions are attractive to ectoparasites and oxpeckers, which can also delay healing.

Though black rhinos are particularly susceptible to invasions of these parasites, white rhinos, giraffes, and several other wild species have also been found with filarial lesions. However, it is still not fully understood why so few cases involve white rhinos, particularly given that the two species are sympatric across much of their range.

Fortunately, concerned observers of these somewhat painful-looking sores can rest assured that these are generally mostly just surface wounds that will clear up on their own each year.

References

Mutinda, M., Otiende, M., Gakuya, F. et al. Putative filariasis outbreak in white and black rhinoceros at Meru National Park in Kenya. Parasites Vectors 5, 206 (2012).

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()