A CONSERVATIONIST INTERVENES IN THE CONFLICT BETWEEN PEOPLE AND PREDATORS

When I was 10, I had clear dreams of my future – I would be a big-cat conservationist, driving around in a shiny zebra-striped Land Rover and spending all my time gazing happily at predators. Here in Ruaha, over 25 years later, some of those dreams have come true – I am a big-cat conservationist, and our project owns three Land Rovers (although none are shiny – they are usually broken – and no one will let me paint them in zebra stripes). However, I rarely get to spend any time watching big cats. Instead, I deal with complexities that I would never have imagined, such as tribal identity, people-park conflicts, and trying to figure out how on earth we can expect grindingly poor people to bear the additional costs of coexisting with dangerous carnivores.

Ruaha is a breathtakingly beautiful wilderness supporting some of the world’s most important carnivore populations, and I feel privileged every day to work here. However, Ruaha’s carnivores are not restricted to the park, but sometimes stray into the adjacent populated areas where they cause intense conflict with local people. The Great Ruaha River runs along the southern border of the park, and in the dry season, it is a magnet for prey and predators. But, during the rains prey animals disperse so carnivores range beyond the park, often preying on poorly-protected cattle and goats.

©Andrew Harrington

When the Ruaha Carnivore Project (RCP) was established in 2009, we found that about 60% of local people had suffered attacks by carnivores. This had crippling economic consequences in an area where 90% of villagers live on less than $2 a day. Unsurprisingly, people frequently snared or poisoned carnivores – either to prevent attacks, or to retaliate for them.

Furthermore, very few people saw any benefits from carnivore presence. Usually the only people who did were young warriors who could receive gifts (zawadi) from their community if they speared a lion – one of the few ways young men could earn wealth and status. A warrior could earn 20 cattle (worth around $4000) in zawadi by killing one lion.

1. A cow falls prey to a predator.

2. A lion was killed in retaliation for preying on livestock. Local people remove sections of lion fur for traditional use as a kind of amulet.

3. A leopard snared in a village. ©Ruaha Carnivore Project

In the early years of the project, most of the lion carcasses we found had the right front paw missing – a clear sign that it had been killed for zawadi, as the central claw is removed and taken to prove the killing. These preventative, retaliatory and cultural killings led to the highest documented rate of lion killing in modern East Africa, with over 35 lions killed in just 18 months, the majority occurring around a single village. So we decided to base our field camp there and try to work out how we could effectively improve the situation for both people and predators.

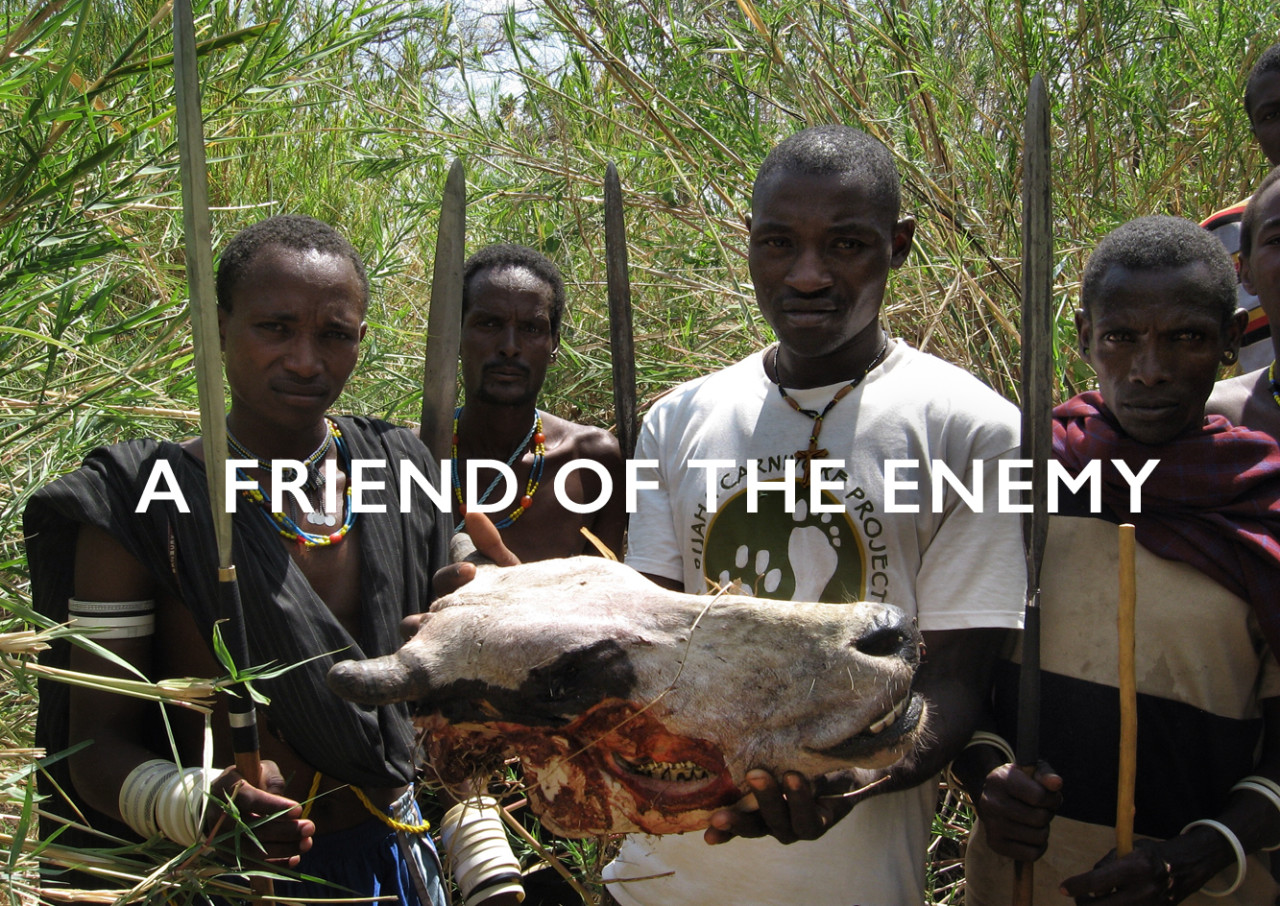

As a long-time vegetarian, I never imagined I would be so happy to receive a huge chunk of meat

But improving the situation depended upon understanding it and gaining the trust of the local community, including the secretive Barabaig, who are notoriously hostile to outsiders. We established a field camp near the village in 2010, but for over a year, our attempts to engage with the Barabaig failed completely. Most villagers would not speak to us, and those who did approach us were beaten up. We tried everything and were almost ready to give up. But then, in mid-2011, it all changed. We installed a solar panel, and bizarrely, that was the breakthrough we needed. The Barabaig suddenly appeared at camp to charge their mobile phones. We would never have imagined that the way to reach this remote and traditional group would be through modern technology, but it provided a reason for people to come to camp, see what we were doing and talk to us. More than two years after the start of the project, the Barabaig invited us to a traditional community meeting. They slaughtered a cow and said they were ready to work with us. As a long-time vegetarian, I never imagined I would be so happy to receive a huge hunk of meat, but I was. It meant that our work could finally begin.

It became clear that the human-carnivore conflict around Ruaha was incredibly complex, involving not only the high costs of depredation but also the lack of benefits to the community, antagonism towards the park, little knowledge about the conservation reasons, and the fact that killing lions was one of the only ways for young men to gain income and status. So we started with the simplest thing – reducing attacks.

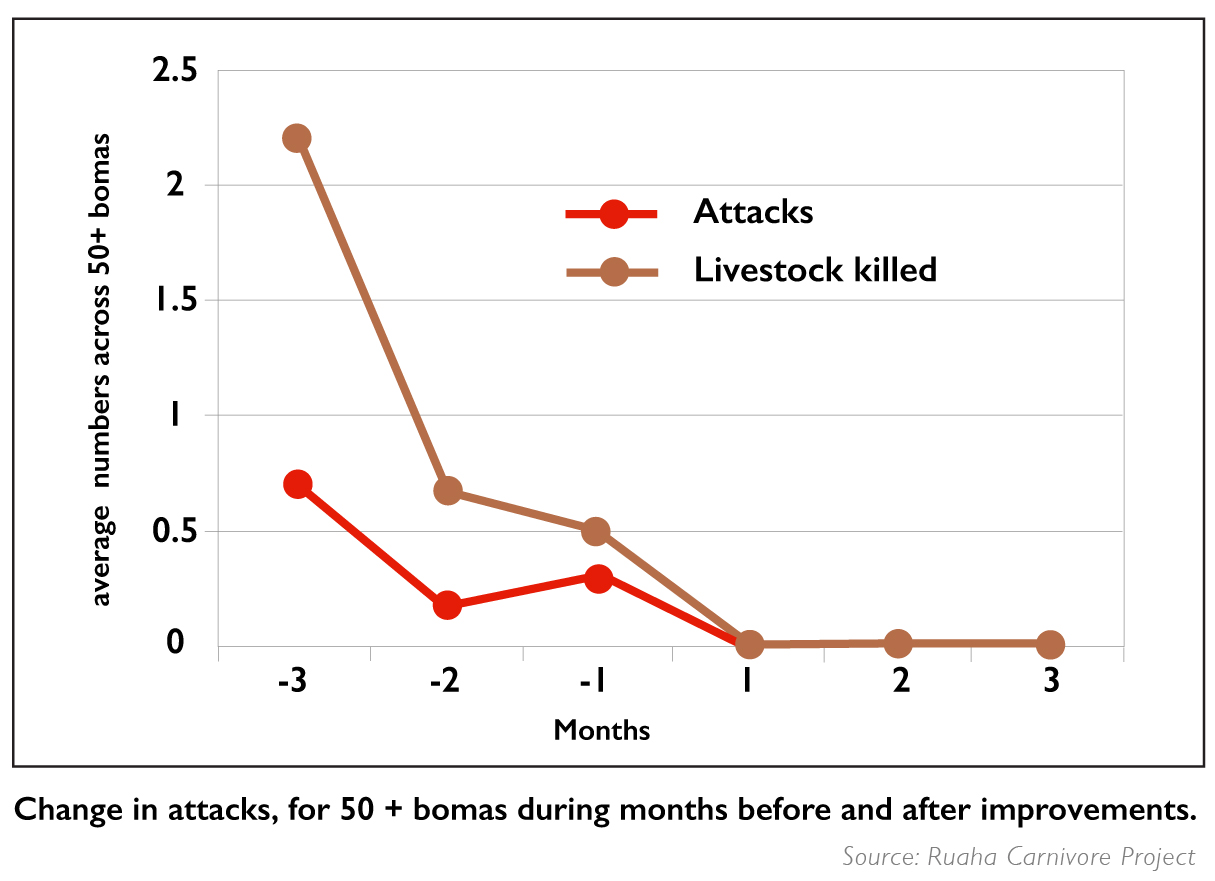

Our research showed that 65% of attacks occurred in livestock enclosures (bomas), the majority of which were poorly constructed. We introduced a cost-sharing initiative to construct predator-proof bomas made of diamond-mesh fencing. To date, we have constructed over 70, and they have proved 100% effective at preventing attacks. However, some attacks occur in the bush, so we have begun trials using specially trained Anatolian shepherd dogs to guard livestock. Although the project is in its infancy, the approach seems promising. In addition, we work intensively with village households to teach people how to identify carnivore attacks and how simple, low-tech measures can prevent such attacks from recurring. Together these measures have significantly reduced depredation, reducing economic pressures on people and the need for preventative or retaliatory killing.

Our research showed that 65% of attacks occurred in livestock enclosures (bomas), the majority of which were poorly constructed. We introduced a cost-sharing initiative to construct predator-proof bomas made of diamond-mesh fencing. To date, we have constructed over 70, and they have proved 100% effective at preventing attacks. However, some attacks occur in the bush, so we have begun trials using specially trained Anatolian shepherd dogs to guard livestock. Although the project is in its infancy, the approach seems promising. In addition, we work intensively with village households to teach people how to identify carnivore attacks and how simple, low-tech measures can prevent such attacks from recurring. Together these measures have significantly reduced depredation, reducing economic pressures on people and the need for preventative or retaliatory killing.

However, living near predators will always mean costs, and long-term conservation depends upon local people seeing tangible, relevant benefits that outweigh those costs. The villagers voted on which benefits they would most appreciate from carnivore presence and chose education, healthcare and veterinary medicines. To improve education, RCP established the ‘Kids 4 Cats’ school-twinning programme, in which village schools are linked with an international school that can help raise funds for much-needed supplies.

We also established competitive ‘Simba Scholarships’ to enable pastoralist children (both girls and boys) to attend secondary school. To improve healthcare, the project equipped a medical clinic in the heart of the pastoralist area, focusing on maternal and infant health. Regarding veterinary medicines, we worked with authorities to help provide subsidised, high-quality medicines to households that had invested in a predator-proof boma. This helps to recoup their initial costs by reducing livestock loss to disease. Although these initiatives are small, significantly more villagers now report seeing a personal benefit from carnivore presence on village land.

1. Opening of a healthcare clinic.©Ruaha Carnivore Project

2. A newly reinforced boma to protect livestock. ©Jon Erickson

3. Visitors to Ruaha National Park learn about the park’s role in conservation. ©Ruaha Carnivore Project

Despite living so close to Ruaha National Park, most local people have never legally entered the Park and knew little about its role. RCP now conducts weekly trips to the park for villagers, enabling them to learn about wildlife in a non-threatening atmosphere. These have been incredibly valuable, with 95% of people saying the experience had (positively) changed their attitude towards predators like lions and 99% saying it gave them a greater appreciation of the park’s role. Education is also provided through DVD nights, which are very popular, and we are now working with international partners to translate some key wildlife DVDs into Swahili for greater impact.

To address cultural killings, we partnered with Lion Guardians and Panthera to replicate the Kenyan Lion Guardian model around Ruaha. Under this initiative, warriors are trained as lion trackers and community guardians. Through this programme, they are given highly-valued literacy training and receive a good income to buy cattle instead of killing lions to obtain them. The Lion Guardians receive status through their jobs and, as influential warriors, dissuade others from going on lion hunts because their jobs, status and income depend on the survival of carnivores in their zone.

Despite challenges at the start, we are already seeing progress. Local people are more economically secure, are seeing real benefits from wildlife and specifically predators, and are gaining conservation awareness. Hearteningly, the largely-Barabaig community just awarded us land for a permanent camp. And let’s not forget the animals. Carnivore killings in the core study area have dropped by 80% since 2011.

There is much we still need to do as RCP works intensively in only a few of the local villages, but we are hopeful as we go forward. My experiences in Ruaha have taught me that, although real big-cat conservation differs vastly from my childhood dreams, it is richer, more complex and more rewarding than that wide-eyed 10-year-old could ever have imagined.

ALSO READ: The emotions of human-wildlife conflict

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()