Africa's behemouth

Sitting in my safari vehicle, on the back end of very little sleep and with the prospect of a rather long night ahead, I waited patiently at the Talek Gate entrance to the Maasai Mara National Park for the grinding wheels of bureaucracy to spit out my ticket. Shamefully, I had my head buried in my phone and was paying very little attention to my surroundings. That changed the instant something breathed soft, warm air into my right ear. My head whipped around, and I found myself face to face with a deep brown, gentle eye fringed with soft eyelashes. It was Mary, the tame Talek eland, and she had come looking for a snack.

Eland: the world’s largest antelope

Though often admired from afar, few people have the opportunity to observe an eland in close proximity. It is one thing to know that they are the largest antelope in the world, but quite another to have the evidence presented at eye level. Sitting in my raised Land Rover (on a cushion that I might see over the front), the eland cow’s shoulder stood above mine and, had the impulse struck, I could easily have leant forward and kissed her on the nose.

Eland antelope are massive animals, standing just under two metres tall and with some more imposing specimens weighing over a ton. The name “eland” comes from the Dutch word for “moose” (or “elk”), and the comparison is a fair one. Though moose stand slightly taller at the shoulder, eland are bulkier, and the two species are closely matched in mass. Eland belong to the spiral-horned antelope tribe, Tragelophini, along with kudu, nyala and bushbuck but are the only members of the Taurotragus genus. Genetically, they are closely related to the greater kudu and, on one occasion, were observed to interbreed, producing a sterile, hybrid offspring. (Interestingly, eland were reported to interbreed with domestic cattle relatively frequently in Zimbabwe during the late 1800s and early 1900s – consistently producing sterile calves.)

Like the other members of their tribe, eland are handsome antelope with pronounced sexual dimorphism. Their colour varies depending on geographic region, but the cows are usually shaded between ochre and tan, occasionally with faint white stripes running down the flanks. The bulls are darker in colour, almost a deep blue at the height of their dominance. Mature males sport pendulous dewlaps, which may play a role in thermoregulation (and possibly social signalling; see below). While both sexes carry a set of twisting horns, those of the cows are usually longer, and the bulls are substantially more robust.

Despite their considerable bulk and impressive helical horns, eland are generally retiring animals and usually move away at the sight of approaching humans. They are also the slowest antelope, relying on their bulk to intimidate potential predators and protect the more vulnerable calves and adolescents. Yet, for all their unwieldy weight, an adult can still leap over two metres into the air from a standing start (a fact that briefly crossed my mind when Mary gave me the side-eye for refusing her food).

A giant of giants

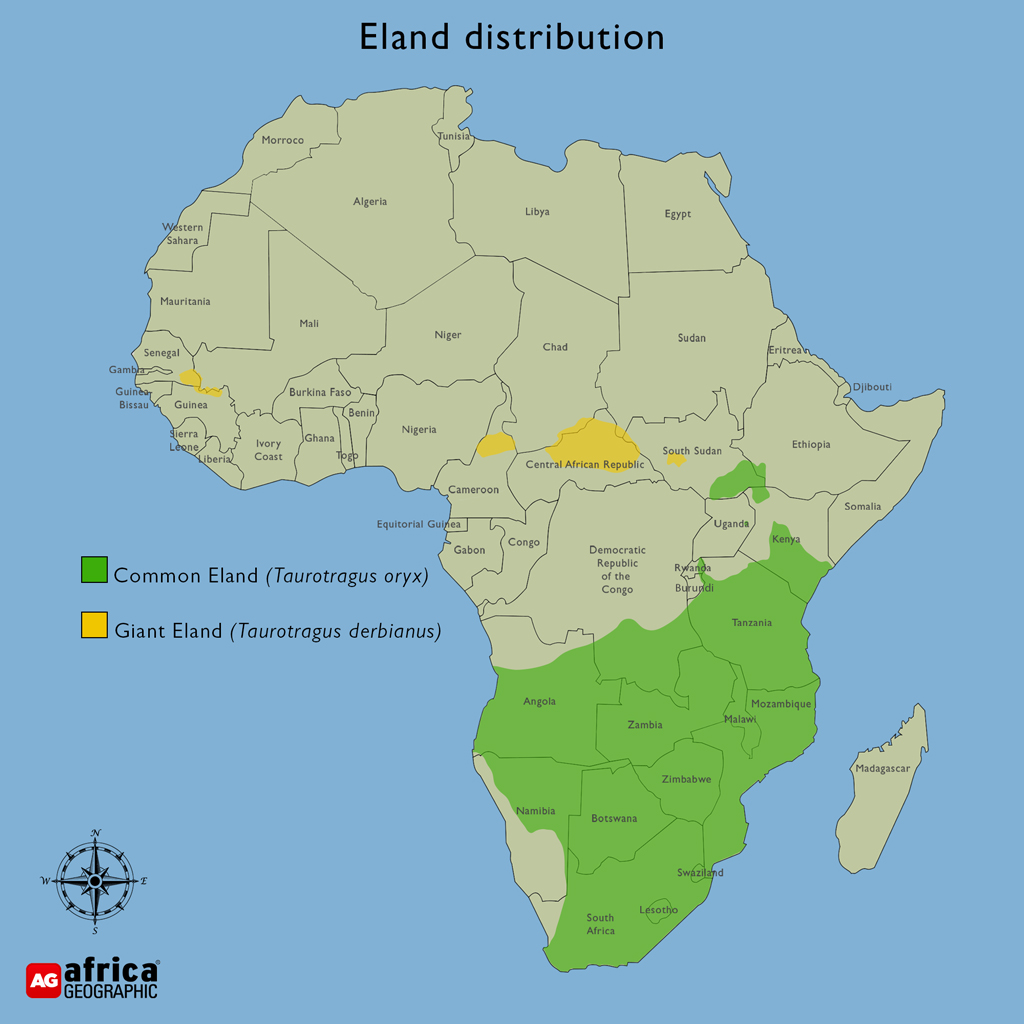

There are two recognised species: the common eland (Taurotragus oryx) and the giant eland (Taurotragus derbianus – also known as Lord Derby’s eland). As one might have guessed, the giant eland is slightly larger than the common eland on average. However, the difference is minor, and the name refers more to the size of the giant eland’s horns. The two animals fall into roughly the same weight class, making the distinction between the largest and second-largest antelope more a matter of pedantry.

Common eland occur on open plains throughout much of southern Africa to Ethiopia and the arid zones of South Sudan. Giant eland are divided into eastern and western populations, the former in Cameroon, the Central African Republic and South Sudan and the latter between Mali and Senegal. Visually, the two species are tricky to distinguish, but the giant eland has slightly longer legs and more vivid markings.

Quick eland facts

| Common eland (Taurotragus oryx) |

Giant eland (Taurotragus derbianus) |

|

| Height (shoulder) | Males: 160cm | Males: 180cm |

| Females: 140cm | Females: 130cm | |

| Mass | Males: 500-900kg | Males: 400-1,200kg |

| Females: 340-445kg | Females: 300-600kg | |

| Social structure | Gatherings of up to 100 (consisting of smaller herds) | Small herds of around 20 individuals |

| Gestation | Nine months | Nine months |

| IUCN conservation status | Least Concern | Vulnerable |

Eland are nomadic (they do not defend territories) and crepuscular, resting in the shade during the day’s heat. They are predominantly browsers but may take advantage of the nutritious grass growth at the start of the rainy season. Eland are social animals, with males, females and immature animals each forming their own separate herds with a linear hierarchy. Older bulls are sometimes solitary.

Clickity clack – don’t talk back

The surprisingly loud sound heard when eland walk has long confounded biologists and the authors of reference books. Some suggested that the click came from the two halves of the hooves splaying open and snapping together when the foot lifted, while others concluded the sound was more likely joint-related. Today, the commonly accepted explanation is that the clicks are produced as tendons slide over the bones of the front carpal joint. Furthermore, though the joints click while the animals walk, male eland also elicit the sound while standing by lifting and lowering their front legs. So, what is the purpose of this peculiar anatomical anomaly?

The answer appears to be that the clicks are part of a complex system of social signalling between males, designed to intimidate rivals while avoiding physical conflict unless necessary. Bro-Jørgensen and Beeston (2015) examined several features, and behavioural traits of 280 male eland observed over eight years. They found that the frequency of loud “knee”-clicks indicated body size and social status. In other words, the deeper and louder the click, the larger and more intimidating the male.

In addition, they identified several other “status badges” – “long-lasting, but reversible, signals of dominance”. In eland, these include a dense growth of dark fur on the face, which forms a face mask that varies depending on the individual’s social status. The dark masks and thick facial fur characterise dominant bulls but regress if that animal loses status or hierarchy. The dewlap size may also serve a similar function, but this has not yet been confirmed.

Captive male eland have been observed to enter into phases of intermittent heightened aggression similar to musth cycles in elephants. This is termed “ukali” in eland and is probably linked to raised testosterone levels, which may physically manifest in darker fur colour and increased hair growth. Similarly, this could relate to the intensity of the clicks because androgen hormones increase muscle mass and strength, and thus the acoustic frequency of the sound produced. Combined, these characteristics serve as signals to rival males.

Eland and people (beyond Mary)

The eland features heavily in the folklore of many African tribes, especially the San people of southern Africa, who frequently included paintings of the animals in their rock art. There are several myths involving the eland, which often represent good fortune, freedom, courage and self-sacrifice. They are also closely associated with the sun, probably due to their light colouring, and were sometimes kept in homesteads for milk and meat. If the milk of a cow was ever used to treat a malnourished human baby successfully, the cow was transported with a guard of honour back into the wild and released as a show of gratitude.

Eland are docile animals that tame easily. The females produce milk with a higher fat and protein content than cows. These factors, combined with their innate resistance to many indigenous diseases and parasites, made them attractive production animals for homestead or small-scale farming operations, some of which still exist in South Africa and Russia.

Common eland are currently not endangered, and the most recent population assessment conducted by the IUCN in 2016 estimated that between 90,000-110,000, mature individuals remain across their range. Giant eland are listed as “Vulnerable” on the IUCN Red List, and their numbers are believed to be declining. Habitat loss, snaring and poaching for bushmeat represent the most significant threats to remaining populations. At last estimate, there were thought to be 8,400 to 9,800 individuals remaining.

Where to find eland

Though widely distributed throughout much of southern and East Africa, the antelope usually occur at low densities and can be surprisingly tricky to find. A visit to Mana Pools National Park in Zimbabwe, Etosha National Park in Namibia or Nyika Plateau in Malawi will offer the best odds of encountering them in the wild. They are also abundant in the Mara-Serengeti ecosystem.

Africa is a land of giants. With behemoths like elephants, giraffes and rhinos, the shy eland is often dwarfed by their more iconic presence. But as my close encounter with Mary reminded me (albeit in an unusual situation), they are magnificent animals in their own right.

References on eland

Bro-Jørgensen, J. and Beeston, J. (2015) “Multimodal Signalling in an Antelope: Fluctuating Facemasks and Knee-Clicks Reveal the Social Status of Eland Bulls,” Animal Behaviour, 102, pp. 231–239

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place

![]()