OPINION POST by Sharon Gilbert-Rivett

Editor’s note: Read the latest news of the Zambia mining story here

On 14 October this year in the High Court of Zambia in Lusaka, a judge is expected to finally hand down a decision on whether an open-cast copper mine will go ahead in middle of one of the country’s prime tourism destinations – the Lower Zambezi National Park.

In a landmark legal case brought by a group of concerned conservationists and NGOs against Zambia’s Attorney General and the mining company involved – Mwembeshi Resources Limited – the forthcoming hearing represents the culmination of years of political intrigue and no small amount of interference by the Zambian authorities, peppered with allegations of corruption and underhanded dealings.

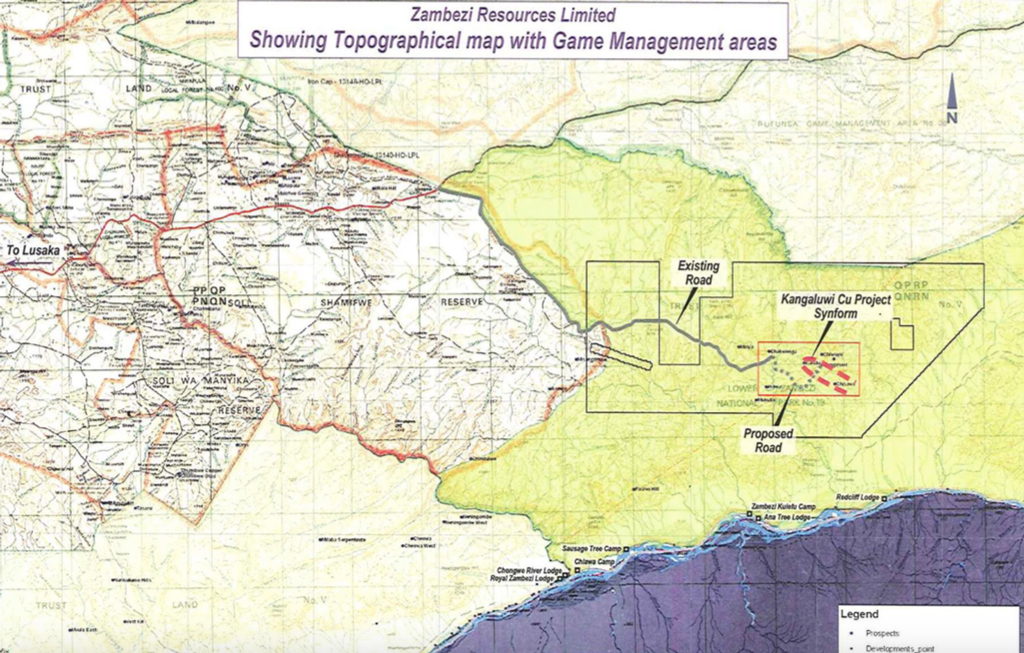

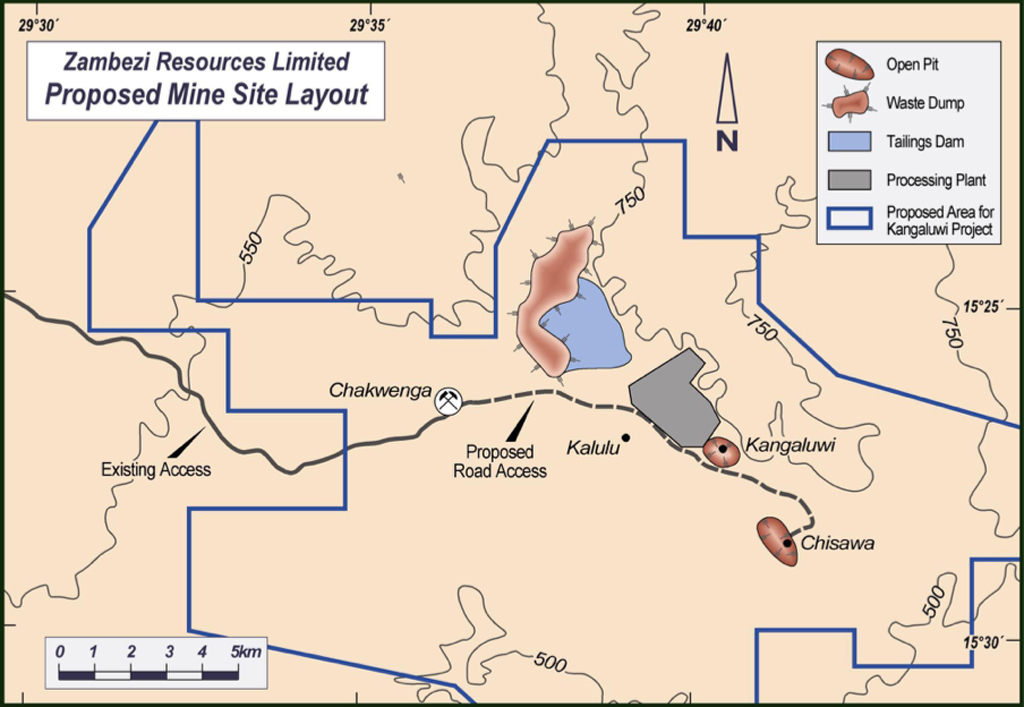

It began some nine years ago when Mwembeshi Resources, a Bermudan-registered subsidiary of Australian-based mining company Zambezi Resources Limited (now Trek Metals Limited) applied for a large-scale mining license for its Kangaluwi Copper Project inside Zambia’s Lower Zambezi National Park, which is directly across the Zambezi River from Zimbabwe’s Mana Pools National Park and downstream of Victoria Falls. Both are Unesco World Heritage Sites.

The application was supported by a prerequisite environmental impact study (EIS) that quickly became the subject of intense scrutiny by tourism stakeholders, conservation organisations and concerned citizenry, all of whom were outraged by the prospect of this globally recognised piece of African wilderness being defiled by mining. The EIS was found to be fatally flawed, not just by an in-depth assessment undertaken by an independent scientist on behalf of the Lower Zambezi Tourism Association (LZTA), but also by the Zambian Environmental Management Agency (ZEMA), which promptly rejected it, stating categorically that the proposed site was “not suitable for the nature of the project because it is located in the middle of a national park, and this intends to compromise the ecological value of the park as well as the ecosystem”.

In a move that stunned all involved and ordinary Zambians alike, in January 2014 the incumbent minister of Lands, Natural Resources and Environmental Protection, Harry Kalaba, overturned ZEMA’s ruling and personally rubber-stamped the project. Thanks to the organisation of a group of conservation-based NGOs who immediately appealed the minister’s decision in the High Court, an injunction granted a stay of execution and Mwembeshi’s mining plans ground to a halt. Although the judge in the matter promised to hand down a final judgement, this final judgement never came. The entire case was consigned to a filing cabinet, where it sat, gathering dust until June this year, when Mwembeshi filed a secondary affidavit, reviving proceedings and the threat to the Lower Zambezi.

In the interim, Zambezi Resources changed its name to Trek Metals Ltd and sold Mwembeshi Resources to a Dubai-based Grand Resources Ltd – a company that is impossible to track down and obtain a statement from. Suspicions are high that Grand Resources is either a front for a Chinese company or is owned outright by Chinese nationals. China seems to be not very highly regarded in this part of the world, especially where the exploitation of natural resources is concerned. In common with many other developing world countries in Africa, Zambia has allowed virtually unrestricted heavy investment from China, and Beijing effectively owns a good portion of the country’s national debt, seemingly taking what it likes in return. It could be one reason why there is such effort being put into greenlighting this project.

“The thing is, we don’t know why Mwembeshi are going to such lengths to push this through,” says Dr Kellie Leigh, author of the independent EIS assessment for LZTA. “The assessment, which was put together with input from several key Zambian mining experts, found not only that the mine proposal failed to address environmental concerns, it was not going to be economically viable based on the information Zambezi Resources itself provided. This was due to the low grade of the ore discovered at the prospect site and the considerable cost of extraction and transportation to either the nearest refinery in the Copperbelt some 500 km away, or off-shore.”

At the time of his intervention, Kalaba had claimed that the reason he overturned ZEMA’s ruling was that “ordinary Zambians” would benefit from the mine through jobs. The ordinary Zambians referred to live in communities contained within the game management areas (GMAs) on the periphery of the park, most notably in the Chiawa GMA which forms the western buffer zone. These communities are dependent on tourism and the income it generates, which has created a sustainable micro-economy in the region. Tourism employs more than 700 people in the lodges and camps strung out along the length of the Lower Zambezi valley, both in the GMA and in the park itself. These 700 people support thousands more in their extended families and communities.

“At the beginning of this case, there were rumours of lobbying going on in the communities here,” says Ian Stevenson, CEO of Conservation Lower Zambezi – a conservation NGO set up by tourism operators in the area that plays a critical role in helping to maintain the delicate balance between protecting wilderness areas and benefitting communities through sustainable development initiatives.

“The communities in the eastern Rufunsa GMA, which has not really benefited as much from tourism due to its geographical location, were encouraged with the promise of jobs, but I question if they were properly informed of the risks associated with the mine,” he says. “In the Chiawa GMA, many residents were not in favour of it as it presented such a risk to the tourism industry and the livelihoods derived from it.

“This sets a dangerous precedent for Zambia’s wealth of protected areas. There’s lots of proposed mines outside protected areas so why don’t the mining companies and government focus on them? This mine will most definitely damage the integrity of the Lower Zambezi National Park in favour of short-term gain, whereas the wildlife and tourism sectors here, if they are protected and managed properly, will last for generations into the future and will bring in significantly more wealth to Zambia.”

Tourism growth in particular seems to be of enormous importance to Zambia, which in July this year unveiled its Tourism Master Plan 2018 to 2038 – a two-decade-long development strategy designed to enhance the economic contribution of the tourism sector. According to Betty Mumba Chabala of the Zambia Tourism Agency (ZTA), tourism is currently the fastest growing sector of the Zambian economy, contributing US$1,8-billion last year to Zambia’s coffers. “The vision is for Zambia to rank among the most-visited holiday destinations in Africa,” Chabala said at the official launch of the strategy, adding that the government is “working hard towards providing an investor-friendly environment”.

Quite how mining inside national parks fits into that growth strategy remains a mystery, as various attempts to reach Chabala for comment failed, and the ZTA phone number seemingly permanently unavailable.

It’s not as difficult to get local Zambians working in tourism in the Lower Zambezi to add their input, but getting them to do so on the record is problematic as most prefer anonymity due to the very real threat of intimidation and reprisals from a government that currently ranks the 105th least corrupt out of 175 countries on the Trading Economics annual Corruption Perception Index, way behind South Africa in 73rd place.

“I am against mining here,” says one lodge worker who has been involved in the tourism and hospitality industry for the last 15 years. “I’ve seen first-hand how tourism benefits people in the local community here, employing people and helping them to enrich their lives, giving them steady income and able to send their children to school. The multiplier effect is amazing. Then there’s our pride in our natural resources as well, this place [the Lower Zambezi National Park] is a place we Zambians are immensely proud of and love to boast about. If we turn it into a mine, what does that say about us as Zambians?”

The effect on neighbouring countries is also of concern.

“What about our neighbours in Zimbabwe and Mozambique?” asks another lodge worker. “How is this going to affect them and how are they going to feel about us if we allow this to go ahead. We could be responsible for polluting the Zambezi. That’s not something that we could ever live with as Zambians. And how would we explain to our peers that we sat back and allowed our government to pollute this incredible natural environment that people from all over the world come to visit and admire?”

How indeed. As the clock ticks down to the 14 October, it can only be hoped that justice in this case prevails, and that the resultant decision is arrived at free from the influence of fraud and corruption that seems to dog the mining industry at large. Perhaps the world spotlight needs to shine on this small corner of Africa. With Swedish teenager Greta Thunberg shaming world leaders for their greed and the west’s political behemoths entrenched in their own political scandals, it may well be that hope alone is not enough to save the Lower Zambezi. Time alone with tell.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()