KINGSLEY HOLGATE'S AFRIKA ODYSSEY EXPEDITION

It’s 47°C at 5pm as we stand to attention alongside hundreds of other cross-border travellers as the Chadian flag is lowered for the day. The border post is strangely still and quiet for a moment, save for the rumble of scores of stationary, diesel-belching vehicle engines and the bleating of a herd of goats making a run for it across the sandy riverbed of the Logone, which marks the boundary between Cameroon and Chad.

Behind us is a 10-day trek through the length of Cameroon, marked by winching fallen trees off little-used, muddy forest tracks, bug-infested wild camping nights, and Ross going down with a bad case of malaria as we reached the northern frontier town of Merowe. That was followed by a bone-rattling, 250-kilometre, truck, bike and ancient Peugeot taxi-dodging hell-run, which took six hours driving more off-road than on; the last scrapings of tar littered with enormous potholes and wash-aways so deep that we had to drive the big Defender 130s in permanent high-lift mode to stop the jagged edges scraping their axles. Also behind us is a four-hour, pillar-to-post border crossing that would’ve been funny if we weren’t so hot, hungry and tired. The last thing we ate was a few freshly made, early morning mandazis (small doughnuts) that Sheelagh bought from a beautiful Cameroon lady swathed all in red as we lurched past her roadside stall after yet another gendarmerie (police) roadblock and all that goes with it.

After much paperwork-shuffling and passport-scrutinizing, we’re finally released from the clutches of customs officials to shouts of “Bienvenue au Tchad!” Ndjamena, the capital, appears like a mirage in the Sahel heat haze; modern glass-fronted buildings reflect the setting sun as thousands of commuters clog the roads, roundabouts and pavements – the noise is deafening and we get lost in the chaos. A friendly soldier flags down a motorbike taxi and leads our expedition convoy the rest of the way; it’s full dark and a massive relief when we finally roll to a stop in the relative quiet of a hotel’s grounds on the banks of the Chari River that flows into Lake Chad. We attack the menu like ravenous hyenas, swallow a couple of cold Galas and head for bed: showers, clean sheets and a struggling air conditioner – luxury after weeks of sweaty and dusty camping. Halala – we’ve made it to Chad!

Renowned African explorer Kingsley Holgate and his expedition team from the Kingsley Holgate Foundation recently set off on the Afrika Odyssey expedition – an 18-month journey through 12 African countries to connect 22 national parks managed by African Parks. The expedition’s journey of purpose is to raise awareness about conservation, highlight the importance of national parks and the work done by African Parks, and provide support to local communities. Follow the journey: see stories and more info from the Afrika Odyssey expedition here.

Early the following day at African Parks’ country HQ, we’re greeted like long-lost friends by Cyril Pélissier, park manager for the Greater Zakouma Ecosystem and country director Monsieur Ahmat Siam. After a quick logistics briefing and shopping for much-needed supplies, we hit the road again – three dusty Defenders in a row with Shova Mike typically ahead on his bike (he’d left at dawn) – en route to one of this year-long journey’s most highly anticipated wildlife regions.

DID YOU KNOW that African Parks offers safari lodges and campsites where 100% of tourism revenue goes to conservation and local communities? You can view and book accommodation in Odzala-Kokoua National Park here, or view other African Parks destinations by clicking here.

DID YOU KNOW that African Parks offers safari lodges and campsites where 100% of tourism revenue goes to conservation and local communities? You can view and book accommodation in Odzala-Kokoua National Park here, or view other African Parks destinations by clicking here.

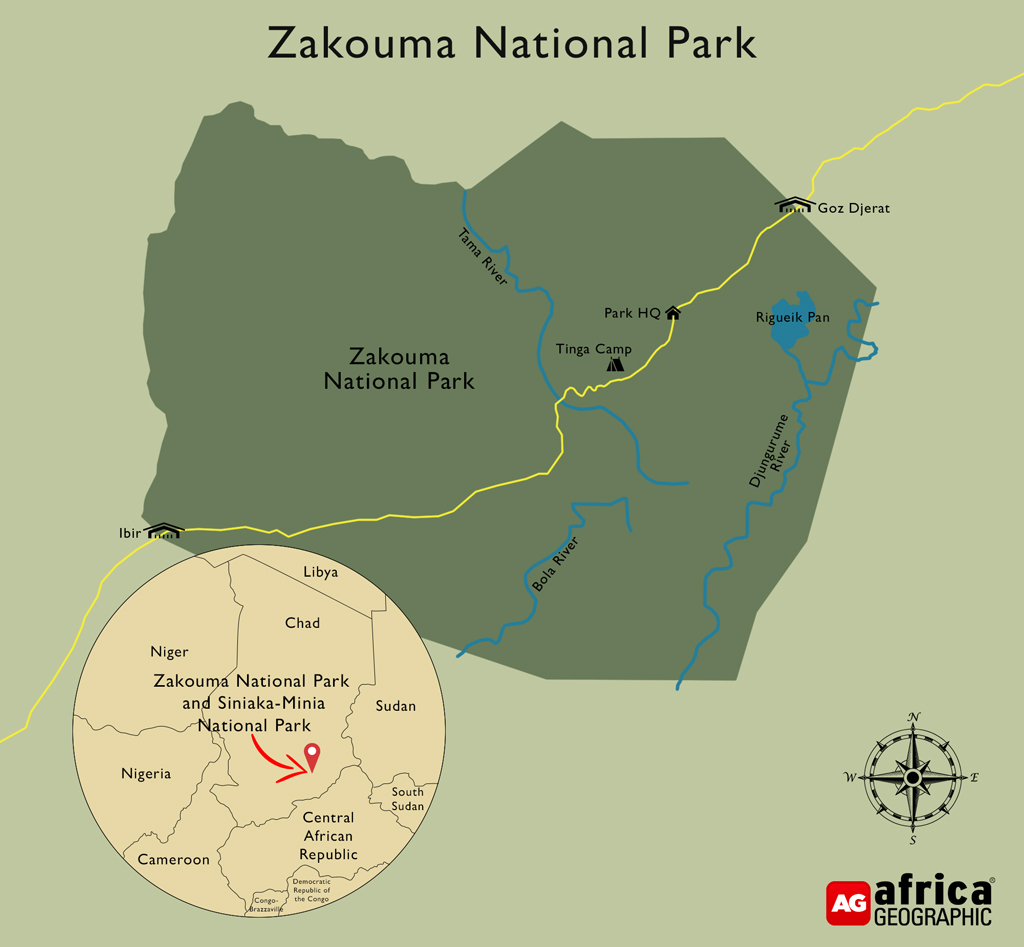

Who would have thought that just south of the Sahara, west of the Nile and north of the Congo rainforests, in a remote corner of Chad close to the borders with South Sudan and the Central African Republic, would exist one of the most inspirational conservation success stories to come out of Africa, and the 17th destination of this Afrika Odyssey expedition?

Zakouma – jewel of the Sahel

Characterised by perennial river systems, floodplains and marshes, savannah, woodlands and seasonal wildlife migrations, the 350,000ha Zakouma National Park is a conservation miracle and something out of Olde Africa. Proclaimed in 1963, it is an essential water source in this harsh environment and home to an incredible array of wildlife. More than half of the world’s critically endangered Kordofan giraffe are found here, along with thousands of buffalo, tiang, Lelwel’s hartebeest, northern greater kudu, oribi, kob, Defassa waterbuck, roan antelope, Bohor reedbuck, lion, leopard, cheetah and hyena and many more species. Recently, black rhinos have been reintroduced, but Zakouma is most famous for its elephants’ story.

Once a stronghold for well over 4,000 elephants, by 2010, Zakouma had lost 90% to ivory poachers – many coming across the border from Sudan on horseback. Driven by the upsurge in demand for ivory and fuelled by civil wars, the gangs would often take out multiple family units at the same time; in just eight years, Zakouma’s elephants plummeted to around 450. Not only were they decimating the elephants and other wildlife, but the Janjaweed (‘devils on horseback’ as they were known) were also wreaking havoc on local communities. Traumatised and terrified, the ellies stopped breeding and bunched into a single mega-herd, their ears torn and ragged from racing through thorn scrub to escape the poachers, many of them still with AK47 bullets embedded in their bodies.

That same year, the Government of Chad invited African Parks into a long-term agreement to manage Zakouma, protect its remaining wildlife and re-establish stability for surrounding communities. In four years, poaching was virtually eliminated, and Zakouma became known as a place of safety, a source of employment and a service provider for residents. Best of all, the ellies started breeding again; once on the brink of local extinction, their numbers are expected to surpass 1,000 soon, and there hasn’t been a single elephant lost to poaching in the past seven years. What an incredible story of hope!

It hasn’t been easy, though. At Zakouma’s HQ, there are 13 framed photographs of Zakouma rangers who were killed by the Janjaweed, some shot whilst at morning prayers. It’s a sombre reminder of how tough the early years were.

But it’s not just about the mammals. Zakouma is a vital stopover and breeding ground for migrating birds. Tens of thousands of spur-winged geese, black crowned cranes, pelicans, Abyssinian ground hornbills, herons, storks, ibis and carmine bee-eaters congregate here, along with hundreds of birds of prey that at this time of year dive into the swooping, charcoal-coloured clouds of millions of red-billed queleas.

Zakouma is also home to the largest number of North African ostriches, a subspecies that’s all but extinct in most of its historic range. It truly is a birders’ paradise – 398 recorded species, to be exact – and one of the largest RAMSAR sites in the world.

Heading for Camp Nomade, Zakouma’s eclectically simple but wonderfully exclusive tented camp on the edge of the Rigueik Pan, it’s fiercely hot. Brahim Arabi, the head guide, welcomes us with big bearhugs, saying, “Ah, Kingsley, you’re back! It’s a good time before the wet season begins; animals everywhere – this place is cooking! The red-billed queleas are here and the black-crowned cranes, the highest numbers ever. The Kordofan giraffe is multiplying, buffalo are in their thousands, and you’ll see lions.”

Brahim can’t contain his excitement; he’s a great example of how African Parks has touched so many lives in such a positive way. “When I started here in 2016, I was just the tailor helping to sew tablecloths, napkins and uniforms for the tourism staff,” he continues. “Then, after two years, I shifted to become a waiter, and during the next three years, after I’d finished doing my table set-ups, I would read through the books in the stretch-canvas dining area and learn about the mammals and birds. African Parks saw my interest, so they sent me to Cameroon to learn English and then to South Africa for guiding and animal tracking training. Back in Zakouma, I developed good relations with many professional South African guides who brought guests. I am now one of the few accredited guides in Chad, and I thank African Parks for everything they’ve done for us; if not for them, we would have lost Zakouma and all our biodiversity.”

At this time of the year, at the end of ‘the dry’, the cracked, black-cotton soil and parched landscape sigh out for the rains. Drying river pools and pans like this one are the only water source for miles. As we’re greeted by the effervescent camp manager, Alice Paghera-Messager, we witness one of the most extraordinary spectacles we’ve ever seen. Bursting with biodiversity, it’s raw, wild Africa in all her glory, and this expedition is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to visit where few people go.

Just a few metres away, an ever-weaving tapestry of mammals and birds unfolds as far as the eye can see. Hundreds of antelope of every type graze placidly, a journey of at least 50 Kordofan giraffes seem to float through a vast haze of swooping queleas, and the air is filled with honking and hooting from thousands of cranes and geese, a trio of big bull elephants glisten with black mud and what appears to be 1,000 buffalo or more appear in the treeline and stroll down to the water’s edge, as marabou storks stalk about like undertakers. Behind camp, there’s the murmur of doves, barking baboons and the distant roar of lions.

Under a brilliant star-filled sky that night, we reflect that this is where the dream of this conservation, community and culture-themed Afrika Odyssey journey first began. We’d been talking about it for years; Sheelagh and Kingsley walking and talking on the beaches of Zinkwazi about searching out stories of hope from across the continent for Africa’s remaining wild spaces and using a stick to scribble expedition names and mission statements in the sand. Then we met Leon Lamprecht, the then park manager of Zakouma, who introduced us to African Parks, and so the story grew and took shape. We are on our most excellent conservation-linked adventure seven years later.

Next morning, in the shade of a huge sausage tree overhanging the open-air dining area, we ask Alice, who’s spent three years running this remote, iconic camp, to list her five special memories: “First, it’s the people and how they quickly adopted me into the Zakouma family. Then the sounds: the mornings filled with the murmuration of millions of queleas literally like waves on the ocean; the hooting of thousands of black-crowned cranes flying in squadrons over the tents; the flapping sound of flamingo wings, the buzzing of bees in the kigelia (sausage) trees, the ever-present cry of the fish eagles and at night, the roaring of lions – sometimes right next to the tents. And the sounds of buffalo, hundreds of them passing close by. I’ll also always remember the musty mud smell of the Salamat River as it begins to dry up, the smell of the elephants and buffalo, the smell of life and death, the unmistakable sweet smell of the Kordofan giraffe, and the smell of the first rains bringing life to this vast floodplain. Fourth – the history and resilience of this beautiful place, the elephants feeling safe enough to breed again and bringing their calves to drink on the pan – a miracle of hope after so much persecution by the Janjaweed. Lastly, every single day, I’m reminded of what an incredible privilege it’s been to be part of this circle of life, not governed by the clock but by the nature that surrounds us, realising just how important ‘wilderness’ is for our inner happiness and contentment, uncontaminated by human voices and mechanical sounds. This reminds me of how lucky I am to have spent time in this pristine and unspoilt part of Africa.”

We are entranced by the spectacle of what we’re calling ‘Africa in the Raw’. Despite the unrelenting heat, there’s no doubt that we’re here at the best time of the year; as Zakouma dries up, the wildlife intensifies around the shrinking pans and pools. There’s much more to do, so we move our expedition base to Tinga Camp, a 1960s-style safari camp from where we explore the riverine bush and countless pools of the game-rich Salamat River and spend time with the Zakouma team at their earth-coloured, fortress-style HQ that harks back to the French colonial years.

Siniaka Minia – Chad’s newest park

However, to remain true to our mission to link all 22 African Parks-managed wildlife areas across the continent, we must also visit nearby Siniaka Minia, just west of Zakouma – number 18 of this expedition. It’s the youngest national park in Chad, with adjoining wildlife corridors and the Bahr Salamat Wildlife Reserve. It now makes up the massive 28,162km² Greater Zakouma Ecosystem, which African Parks has been mandated to manage.

It’s a long, dusty road for the hard-working expedition Defenders, winding through awe-inspiring inselbergs and mud-built villages with steeply thatched conical roofs, each with a top-notch that makes them look like a witch’s hat. Outside each homestead stands a gigantic, beautifully handcrafted clay-pot granary to store the sorghum and maize that make up the staple diet of this region. Men on horseback drive vast herds of cattle, goats and fat-tailed sheep, whilst groups of colourfully dressed, laughing women enjoy the daily chore of walking their donkeys ladened with containers to fetch water.

At the village of Malfi, whilst sitting with Yves Holma and his Siniaka Minia community team, the expedition map spread before us; the unbelievable happens – something we’ve been dreaming about after weeks of mind-numbing heat and sweat. A huge dust storm suddenly rises several hundred metres into the air, there’s a massive crack of thunder, the skies darken, the temperature drops, and soon we’re enveloped in wind-blown, ice-cold rain that has everybody sprinting for cover. “Run for it! Get in your cars now!” shouts Yves as he pushes Ahmat Youssoup, one of the community liaison officers, into the Defender’s passenger seat. “He’ll show you the way to the Samer basecamp in the middle of the Park. Go quickly before the road gets too wet.”

The excitement of the village camels is palpable as they frolic, kick up their back legs and rush to drink from quickly forming puddles in the road. A horse-and-cart driver strips off his tunic and stands with arms outstretched, a big smile on his upturned face. But just as suddenly as it starts, the storm is over. “Still too early for the big rains,” remarks Ahmet as we race into the dark, twisting and turning through the endless bush country to reach the Park’s HQ, where under a simple stretch of canvas near a small waterhole, we meet Guy Mbone, the instantly likeable Ops Manager and experienced conservationist, who speaks the local dialects and hails from Bangui in the Central African Republic.

He explains that Siniaka Minia was officially declared a national park six months ago, making it Chad’s fifth and largest national park and securing this region’s important wildlife migration corridors. When the rains come and Zakouma floods, this new park becomes their haven. Darren Potgieter, a South African bush pilot who played a role in the translocation of 900 buffalo to Siniaka Minia from Zakouma, adds, “You can see the encroachment from the air; if we don’t protect these wildlife areas, they will soon be lost to livestock and sorghum fields.”

Later, Darren writes these words in the giant African Parks’ Scroll of Hope for Conservation that the expedition carries across Africa: ‘Welcome to the hot embrace of Siniaka Minia! May your footsteps echo with the resilience of the wilderness, and may your encounters with wildlife and communities inspire shared passion and commitment to preserve and protect.’

This Afrika Odyssey journey is not just about the wildlife; it’s also about joining forces with the community liaison teams, who are putting tremendous effort into assisting the villagers living alongside both Zakouma and Siniaka Minia. It’s not just about jobs – although they are now the largest employer in the region – it’s also about income generation and commercial community projects. Twenty-nine farmers’ organisations now produce vegetables, fruit, chickens, chebe (a natural hair moisturiser used by women of the Basara people in Chad and further afield), shea butter, desert date oil and honey.

Twenty-six schools attended by more than 2,400 children are supported with educational materials, stationery, furniture and school supplies. African Parks has also built three new schools, and as part of the environmental awareness programme, over 6,800 children visited Camp Dari last year, which has been set up in Zakouma for school groups. In the words of 13-year-old Ahamat Aradi from Goz-Djarat primary school, ‘Zakouma must keep the animals safe. We need them for future generations because if the animals disappear, humans will also disappear. And if we cut the trees, we will bring the desert here. If there is no rain, people will die because we will have nothing to eat.’

As it’s been throughout this expedition, we get involved in a chunk of community work at both Zakouma and Siniaka Minia: educational wildlife art competitions with the kids, malaria prevention education and life-saving mosquito nets for village mums, and eye tests and reading glasses for the elderly.

Later that day, there’s the symbolism of collecting water in the expedition calabash; at Zakouma, Cyril Pélissier is given the honour; at Siniaka Minia, it’s Guy Mbone’s turn.

On our last night, Alice asks the expedition team who’ve travelled so hard and far to get to this distant, wild corner of Chad to list their favourite Zakouma memories. “It’s mindboggling; thousands of catfish in the bubbling pools of the Salamat, buffalo stuck in the drying mud with lions lazing on the banks just biding their time, Kordofan giraffe at every corner… this is a once-in-a-lifetime experience,” says expedition leader Ross.

Sheelagh, who flew doors-off in the small Savanna aircraft with pilot Nicolene de Beer on a black rhino monitoring flight, is amazed by the endless vistas of wilderness, especially the vast woodlands of Acacia Sayel (red-barked gum arabic trees) stretching to the horizon, and a birds’ eye view of the winding, luminous-green Salamat River, with thousands of crocodiles pockmarking its surface glowing yellow in the sunlight, and vast herds of buffalo and elephant with not a human being in sight. “Seen from the air, Zakouma is a giant, almost primaeval landscape,” she tries to explain.

“For me, it’s the lions,” muses Shova Mike, who’s cycled much of the expedition’s route to Chad. “I’ve never seen such unusual sightings, plus the incredible bird life, and I want to see firsthand the great work being done here by African Parks. It’s been well worth the miles of pedalling.” Anna agrees: she’s astonished by the abundant bird life, especially the brilliant-coloured carmine bee-eaters in their hundreds diving and swooping from condominiums of nesting holes in the banks of the Salamat. Fiona loved the isolation and uniqueness of Camp Nomade. “It was as if we were the only people in the world, surrounded by a kaleidoscope of nature – roan antelope, reedbuck, waterbuck, kob, giraffe, hartebeest – and birds, birds, birds!”

For Kingsley, of course, it’s the elephants, which are his favourite animal. “It’s inspiring that after all the years of suffering and killing for their ivory, Zakouma’s elephants are thriving again; a wonderful story of hope that makes this journey all the more worthwhile,” he concludes.

Too soon, our time in this extraordinary landscape that retains a powerful sense of what Africa must have been like a few centuries ago has to end. Cheerful workshop staff help fill up the Defenders’ jerry cans and drinking water tanks, check tyres, scrape the worst of the mud, and dust off the windows and headlights. Ahead lies a long journey deep into the Sahara to reach the next expedition destination, which we’re all extremely curious about, and the unbelievable Ennedi Cultural and Wildlife Reserve close to the border with Libya.

Further reading

- Zakouma – a park returned to vibrant wilderness teeming with life, is a once-in-a-lifetime journey for travellers looking for safari adventure. Read more about travelling to Zakouma National Park, jewel of the Sahel, here.

- A visit to Zakouma, central Africa’s last wildlife stronghold, means going back to old-school, authentic safari values. Read more about a safari to Zakouma here.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()