DECODING SCIENCE POST by AG Editorial

Researchers have conducted a lengthy pre-published study indicating that the lesser-known wildebeest migration patterns throughout East Africa are facing grave peril. The scientists point to population growth resulting in: range restriction, degradation and loss of habitats, agriculture, poaching and artificial barriers such as roads and fences. They highlight the necessity of urgent conservation measures and commitment from the governments of both Kenya and Tanzania.

Understanding migration

The yearly Great Migration of over a million white-bearded wildebeest and zebra through the Serengeti and Maasai Mara ecosystems is perhaps the most renowned large mammal migration and generates enormous tourism revenue. Importantly, the study notes that these populations are not under threat, and their movements are mostly unrestricted. However, poaching is still a challenge for conservation authorities. Though by far the largest, this is not the only wildebeest migration in East Africa. The scientists emphasise that conserving smaller populations and migrations is essential for several ecological and socio-economic reasons.

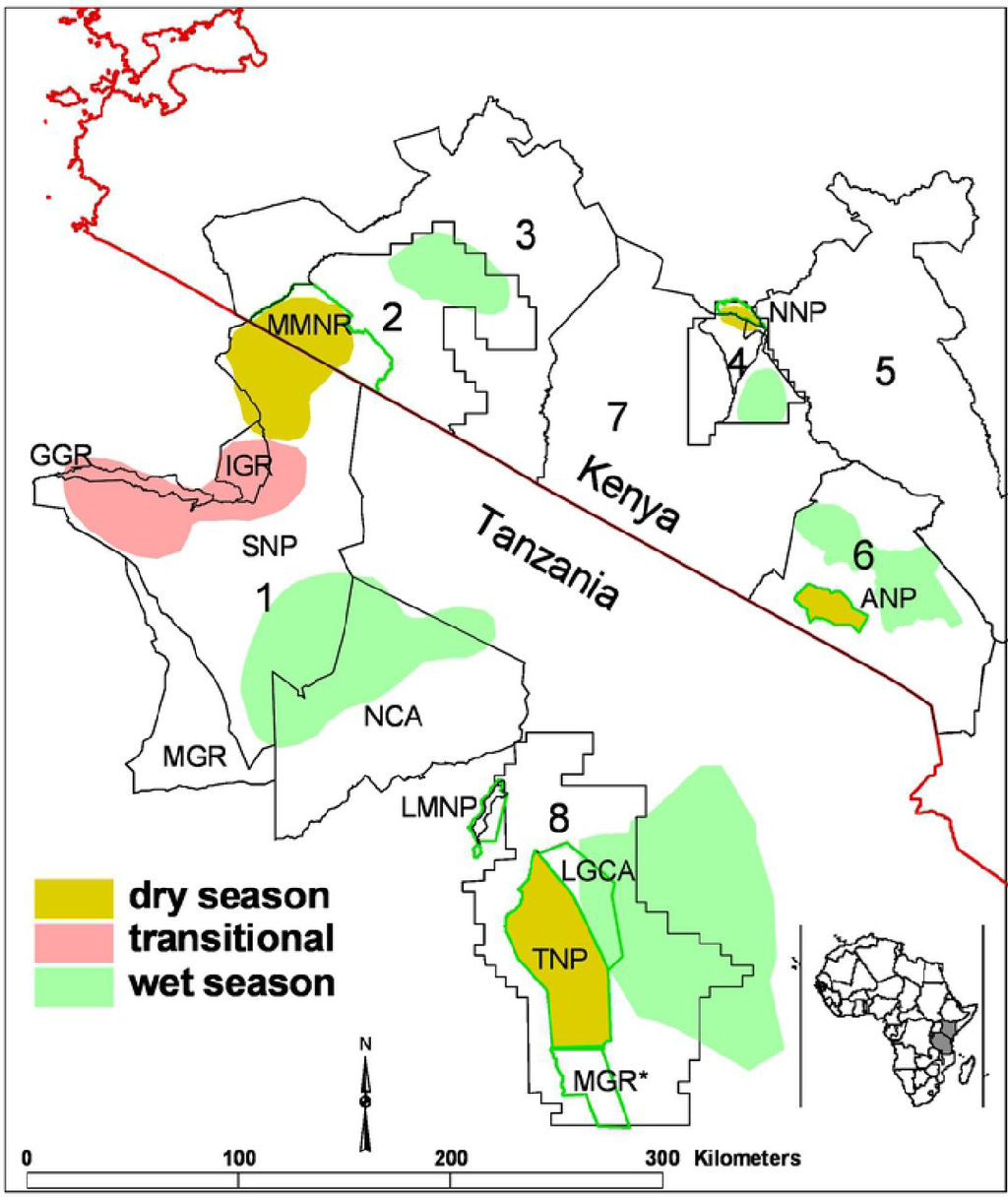

Protecting a migratory route involves complex analysis of the context in terms of the human populations of the land. Integral to this study was research into historical wildebeest migration patterns as well as their current status. Researchers attained historical information through literature reviews, colonial-era records, maps, GIS databases, records of GPS collared wildebeest and interviews with residents and researchers alike. For current movements and status information, 36 wildebeest across the study range were collared, and their movement tracked for two years. Wildebeest population estimates used external data compiled by aerial surveys and various governmental, development and wildlife organisations provided the data on the anthropogenic aspects of the analysis.

Disappearing wildebeest

This approach was made all the more complicated by the fact that irreversible changes to the migratory populations and routes that occurred as early as the beginning of the 20th century. With this in mind, scientists examined the Serengeti-Mara, Maasai-Mara, Athi-Kaputiei, Amboseli Basin and Tarangire-Manyara ecosystems and came to the following conclusions:

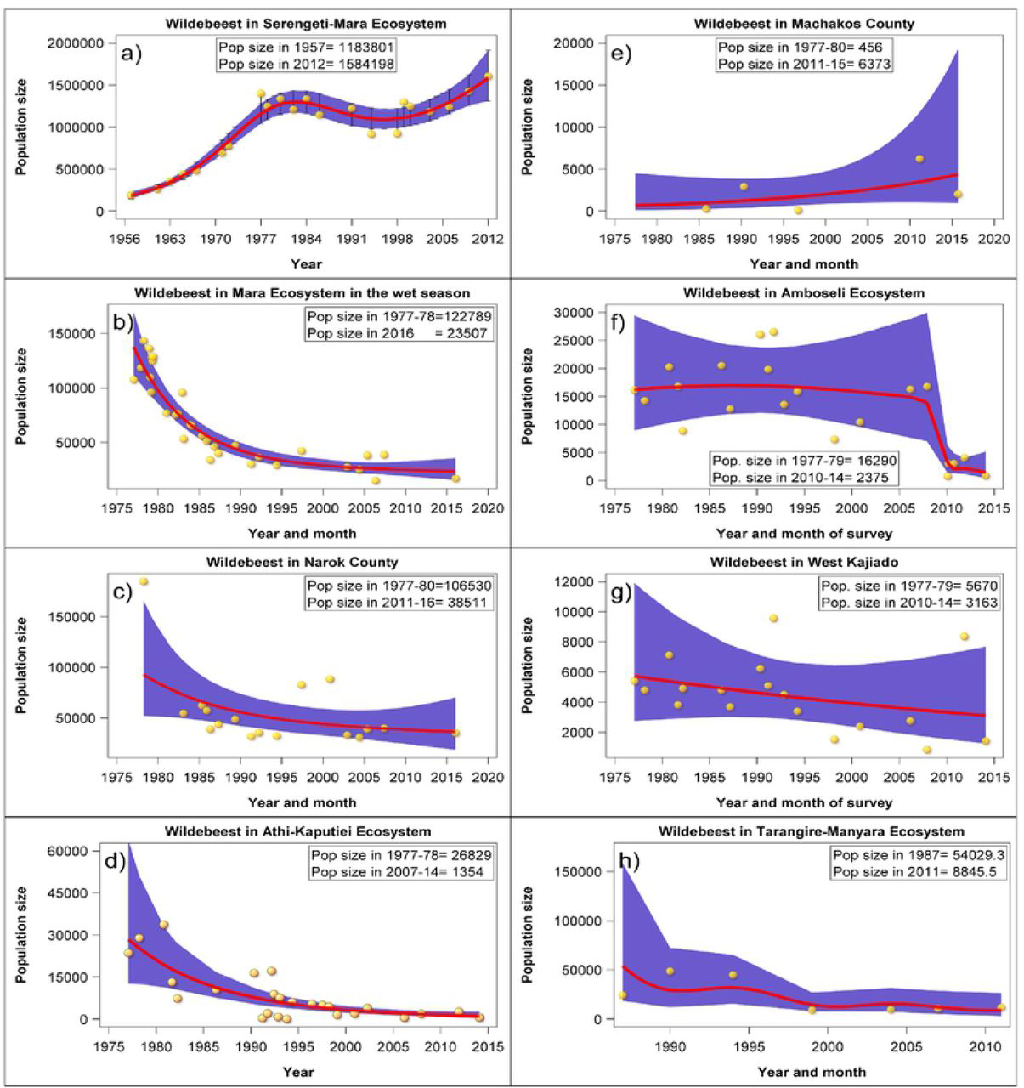

- Serengeti-Mara – as discussed, though the migratory routes have changed slightly, the numbers have remained stable (currently around 1.3 million animals) because the migratory pathways occur mostly within protected areas. Referred to by researchers as ‘southern migration.’

- Maasai-Mara – during the dry season (July-October) as the Serengeti wildebeest move north into the Maasai Mara, wildebeest from the Loita Plains descend to the conservancies surrounding the Maasai Mara National Reserve. Their numbers have declined 80.9%, from 123,930 wildebeest in 1977-78 to less than 20,000 in 2016. Referred to by researchers as ‘northern migration’.

- Athi-Kaputiei ecosystem – includes Nairobi National Park, Athi Plains and surrounding areas. This population has declined 95% from over 26,800 in 1977-78 to under 3,000 in 2014, leading to a “virtual collapse of the migration”. It is important to note here that researchers believe that many of these wildebeest have moved, rather than died in such enormous numbers.

- Amboseli Basin – includes Amboseli National Park and surrounding pastoral lands in Kajiado County. The population of the Amboseli ecosystem declined 84.5% from 16,290 in 1977-78 to 2,375 by 2014.

- Tarangire-Manyara ecosystem – incorporates both national parks and private conservancies in Tanzania. The population declined from 48,783 in 1990 to 13,603 in 2016 and shows no signs of recovery.

As can be seen from the above, four out of the five studied migrations are at the point of disappearing completely, particularly the Athi-Kaputiei population. As wildebeest numbers have dropped, the human populations have soared: a 673% increase in Narok County (including Loita Plains), 905% in Kajiado County (Incorporating the Amboseli Basin), and a 247% increase in Machakos Country – all from 1962 to 2009. Increased human numbers means increased agriculture, increased sedentarisation and settlement of formerly semi-nomadic populations, and more fences and roads that occlude grazing resources and routes. In Kenya, the increase of private land ownership has changed the game, and in Tanzania the Game Controlled Areas have been cultivated.

The study expressed frustration at what the researchers describe as “incoherent government development policies that promote incompatible land uses, such as promoting cultivation pastoral rangelands occupied by wildlife to combat food insecurity while also promoting wildlife-based tourism in the same areas”. In Kenya, landowners do not have access or user rights over the wild animals on their land and are often offered no compensation for the cost of supporting wildlife. While there are several changes in policy and legal framework, none of these has been adequately implemented.

Hope going forward

The study acknowledges the existing governmental and conservation efforts in both Kenya and Tanzania that have gone some way towards mitigating the effects of expansive population growth, particularly in the development of policies on corridors, dispersal areas and buffer zones to create habitat connectivity. The researchers highlight the system of conservancies within Kenya – private landowners (either individually or as an amalgamation) rent out large sections of land to tourism operators for game viewing. In Kenya, around 65% of wildlife occurs outside of protected areas, so the rapid growth in popularity of conservancies is a positive development. They do, however, require a sustainable tourism potential. In Tanzania, the creation of the Tanzania Wildlife Authority as well as the reorganisation of the entire wildlife sector into paramilitary-style organisations to intensify the fight against run-away poaching, have both been positive steps. However, these efforts need to be enhanced by economic incentives to communities.

“The Kenyan and Tanzanian governments need to strongly promote and lead the conservation of the remaining key wildebeest habitats, migration corridors and populations and more conservancies or management areas should be established to protect migratory routes or corridors, buffer zones, dispersal areas and calving grounds for the species.” The plight of the white-bearded wildebeest is one that represents a far more significant challenge facing the wildlife of Africa.

Full report: Wildebeest migration in East Africa: Status, threats and conservation measures

Fortunata Msoffe, Joseph Ogutu, Mohammed Said, Shem Kifugo, Jan de Leeuw, Paul Van Gardigen, Robin Reid, JA Staback, Randall Boone – hosted by bioRxiv

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()