THE GREATEST AFRICAN ELEPHANT CENSUS IN HISTORY TAKES TO THE SKIES

A jetliner is a wondrous thing; a spaceship: stupendous. But an unsophisticated propeller plane is far more significant. Flying no higher than a bird, this machine gives us enviable perspective on the creatures below – things invisible from jetliners, and mere concepts from space. Looking down on our planet must be incredible, but seeing the big picture depends on looking much closer to home, and what could be more incredible than gazing upon elephants – Africa’s giants.

As you read this, Dr Mike Chase, founder of Elephants Without Borders, is in all likelihood perched in a little propeller plane searching for African elephants. Nobody is really sure how many are left. Speculation puts the number anywhere between 410 000 and 700 000 – down from an estimated 27 million in the early 19th century. Surveys in the past have been area-specific and fragmented in both time and space, and some key populations have not been surveyed in 10 years.

EWB conceptualised The Great Elephant Census. Funded by Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen, 18 planes and 46 scientists are racking up thousands of air miles performing approximately 19 000 transects covering 600 000km. This extensive aerial survey, conducted in the relatively short space of eight months, will give an incredibly detailed snapshot of the African continent – in essence, it will be the ultimate ‘Big Picture’.

“It’s far more significant than establishing the number of elephants,” explains Chase. “We’re recording data on all types of wildlife and ecosystems. We’re documenting the effects of human encroachment and poaching. There’s no other data on the status of Africa’s habitat on such an immense scale.”

Chase’s first flight took off in Kenya’s Tsavo National Park in February, and so far, he’s been encouraged by the number of elephants there. Kenya Wildlife Service considers the 41 660 square kilometre Tsavo Ecosystem – about the size of Switzerland – the most important area for elephants in Kenya.

“Given what we’ve read in the press, I was expecting to see a landscape strewn with freshly poached carcasses, but we didn’t see even one after nearly a hundred hours of flying.” The carcasses Chase did see were shown to him by the park warden. “They do indeed have a poaching problem in Tsavo, but it’s not of the magnitude portrayed, and I attribute that to the diligence and commitment of the KWS. Their policing and anti-poaching patrols are paying off.” A total aerial count by KWS gave a preliminary number of 11 076 elephants – down from 12 573 in 2011. They consider this a stable figure, given the poaching problem. EWB’s sample aerial count gave a reliable estimate of 14 000 elephants in the area at any time. Learn how the aerial counts were conducted.

Leakey ignited the world’s imagination by setting 12 tons of ivory alight

Tsavo National Park, established in 1948, has gone through many cycles of success and tragedy and is the embodiment of a typical African national park. Through concerted effort, it has played a key role in reviving elephant populations that were decimated by hunting for both ivory and ‘sport’. By the early 1960s, Tsavo had essentially reached elephant-carrying capacity. In 1969 the Tsavo ecosystem supported an estimated 42 000 elephants. Sadly, a prolonged drought in the early 1970s led to the death of some 6 000 – mainly female and juvenile – elephants. After the drought broke, many surviving large bulls for which Tsavo was renowned became the first poaching victims for their incredibly large tusks. As the remaining bulls became more and more difficult to find, large females were targeted. Then, as demand grew, smaller and younger elephants were slain for their paltry tusks. This, combined with the drought, severely hampered population recovery, and by 1979 there were as few as 12 000 elephants left in the Tsavo ecosystem. By 1989, what some consider to be the height of the east Africa poaching crisis, only around 6 000 remained.

At that time, Richard Leakey, the head of Kenya’s Wildlife Conservation and Management Department (soon changed to Kenya Wildlife Service), ignited worldwide recognition of the elephants’ plight by persuading Kenyan President, Arap Moi, to set alight a 12-ton stockpile of ivory. Leaky created crack anti-poaching units that were authorised to shoot poachers on sight, and more stringent limitations and bans were placed on the international ivory trade. Elephant numbers rose steadily in east Africa. But as ivory trading goes on largely uncontrolled in Asia, and as Chinese wealth grows, poaching continues to ravage Kenya’s elephant population. It has also increased drastically in other regions, such as southern Tanzania, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Chad.

Apart from elephants, the team is counting conservation islands. With Kenya’s growing population of 42 million, wild animals are being squeezed into isolated islands of refuge. “Sitting at 300 feet, you get a broad sense of how small these islands are and how devastating the environmental aspect is as soon as you leave the national parks,” says Chase. “You look on the African map at the scattering of parks. You imagine that these sanctuaries are protected islands of pristine nature. But they’re not. The people on their periphery cannot live off the land outside of the parks. It’s been over-utilised, and denuded. They’re crossing over onto these islands to survive, and the islands will go the same way if it’s not stopped.”

They are counting people and livestock. “We saw high densities of wildlife living alongside people and domestic stock.” In Southern Kenya, the Maasai, who were once free to range, are effectively trapped between parks and conservancies. Here they are reliant on the parks to feed their cattle and themselves. As a result, Chase counted far more cattle in Tsavo than elephants. There is also the pressure of human/elephant conflict. As elephants threaten crops and villages it is not unusual for people to attack them in retribution or to scare them off, often using poison-tipped arrows or spears that can lead to slow, painful deaths. Then there is the issue of charcoal.

Elephants are second only to humans when it comes to the devastation they can wreak on woodlands

They are counting fires. On Tsavo’s horizon, Chase saw many plumes of smoke rising from rudimentary charcoal kilns. Getting closer, he saw how vast numbers of trees had been cut down and carried to central points where compact beds of wood were laid and covered with a thick layer of soil. “The wood is set alight, and slowly the compressed wood burns – producing briquettes of charcoal, which are packed into sacks for the market. It’s a laborious process,” Chase explained in a blog post on EWB’s website. “They are marvels of African architectural ingenuity and labour. You can see the influence of their work quite clearly from my vantage point. Massive areas of acacia woodland have been denuded. I gaze down on them and their work with respect and empathy. The hard-working people I see below me must be turning a good profit to struggle like this. The depressing scale of the charcoal trade is heightened by a landscape littered with temporary living quarters constructed from colourful plastic bags fluttering in the wind. What do these hard-working souls eat out here, how many trees are cut down to fill a bag with 50kg of charred wood?”

Elephants are second only to humans regarding the devastation they can wreak on woodlands. Culling and translocating elephants is an important part of wildlife management in southern Africa, where elephant populations are much larger and have a far greater impact on woodland. In Tsavo and other parts of East and central Africa, poaching has performed a cruel service by keeping elephant numbers down – and so culling is practised much less frequently. But as it has become harder for poachers to kill elephants in Kenya, many have turned their machetes, axes and chainsaws, once used to extract tusks from elephant skulls, onto trees to profit from the illegal manufacture of charcoal. What aggravates the problem is that the militant Islamic group al-Shabaab, supposedly drives much of this illegal trade. If it continues at the scale Chase indicates, it could be more detrimental to Tsavo’s elephants than poaching due to the destruction of their natural habitat and the pressure it will put on the entire ecosystem. Learn how charcoal fuels al-Shabaab’s terror campaigns.

In April, African Parks, an organisation determined enough to manage wildlife areas on the sharp end of poaching, flew Chad’s 3 000-km2 Zakouma National Park as part of the Pan-African survey. Zakouma’s elephant population has suffered terribly during the last decade under the poacher’s gun. The estimated 4 300 elephants in Zakouma in 2002 had been reduced to 450 in 2011. Preliminary reports after the latest count suggest this number is now stable, a credit to African Parks, who took over management of Zakouma in June 2010. They have greatly increased efforts to protect the remaining elephants that move in larger-than-normal herds, possibly as a survival strategy.

Well-armed poachers are now targeting Garamba National Park in north-eastern DRC, also managed by Africa Parks. The park is effectively a war zone, with ongoing firefights between park rangers and members of the terrorist group the Lord’s Resistance Army. Equally worrying is the implication that a Ugandan military helicopter has been used for poaching activities here.

A previously undiscovered herd of elephants in paradise

As I’ve had further contact with Chase, a typically upbeat man, I detect the gravity of these observations in his voice. Reporting from Ethiopia at the end of May, he was surprised to find that people dominated the 7 000-km2 Babile Elephant Sanctuary. It was supposedly home to the last remaining elephant population in the horn of Africa but of the 300 elephants believed to be there, he spotted only a few dozen after 60 hours of flying. In contrast, other animal counts were much higher. He estimated 40 000 camels, 200 000 head of cattle and 450 000 goats wandered the park. But his spirits pick up when he mentions “an elephant paradise, a habitat ideally suited to these giants.” And in it, an undiscovered herd. Understandably, he’s reluctant to divulge the location and the number of elephants he found there, but it’s significant. It lifts his voice as he describes the excitement of an Ethiopian elephant biologist they took up to count a herd. “You should have seen his reaction looking down on those elephants. You won’t believe it, but this biologist had never seen one before.”

All the while, the survey is engaging local scientists and conservationists, training them as much as possible, giving them access to the data, and allowing them to study their environments from the air. Chase stresses that, unlike many research programs, he does not leave a country without first sharing the raw data with the local conservation authorities.

As of writing, three planes and 18 team members from the Tanzanian government, several wildlife organisations, and the Frankfurt Zoological Society are coming to the end of a joint aerial census of the entire 30 000-km2 Serengeti Ecosystem in Tanzania. The Wildlife Conservation Society, which is conducting surveys over more countries than any other census partner, is due to begin surveying elephant populations in the Central Africa Republic and Mali.

After Ethiopia, Chase and his team will survey Namibia’s Caprivi Strip and parts of Botswana, together with some of neighbouring Angola, Zambia and Zimbabwe, to form the extensive 444 000-km2 Kavango–Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area. This part of Africa is supposedly home to more than half of the continent’s elephants. Over the next four months, a large number of planes will take to the southern Africa skies – including over the Kruger National Park.

“North of the Zambezi, more and more elephants are moving at night. Fear of poaching has changed their behaviour,” Chase says. They are far less threatened in the south. The success of the southern populations is not just a story of concerted conservation efforts. As Chase stresses, “it has to do with stable government and economy and recognising the value of tourism. The southern countries, even Zimbabwe, with all its challenges, have done a good job of protecting their natural heritage because they know that’s what people will want to come and see – that it provides income and jobs and that it must be sustained.

“The next part of the survey is going to be really interesting. There’s long been a dispute over whether Botswana is over-estimated (figures put the number at over 133 000 elephants – by far the highest of any country and more than the entire elephant population of East Africa). Angola will be an adventure of discovery. We’ll see what numbers have returned since the end of the civil war. There’s also southwest Zambia of which so little is known.” You can detect the excitement in Chase’s voice, the potential of a new discovery. A new elephant paradise, perhaps.

As busy as he is at 300 feet, Chase does have the chance to appreciate the beauty and diversity of the landscape and wildlife. In Tsavo, he was particularly struck by the sight of some of the legendary tuskers for which the park is renowned. It’s believed there are no more than 30 left on the continent. “Watching these majestic giants is a great opportunity to marvel over these behemoths with one hundred-pound tusks on either side. They are truly nature’s great masterpieces.” Chase was one of the last people to see the famous Satao alive – shortly before his carcass was discovered after poachers had killed him for his immense tusks.

In 2015 the work will continue to assess, compile and combine all the country reports into a single, impartial analysis for all conservation authorities and decision-makers to use. The story of elephants, and Africa, will become much clearer.

While these simple flying machines survey the rich earth below, we spend billions on sophisticated spacecraft to survey the dust on Mars. In doing so we deny our own terrestrial splendour and lose sight of our responsibility to preserve this planet. Paul Allen has spent a considerable amount of money funding ventures in space tourism. But while this might enable a privileged few to gaze down on the planet, this latest venture of his, conducted at just 300 feet, is far more noteworthy as it will help protect our planet’s wonders. You can’t see Africa’s giants from space.

Contributors

KELLY LANDEN threw down an anchor in 2002, abandoning a career on the oceans to dedicate herself to African conservation. Having a passion for wildlife and an affinity for photography, as Elephants Without Borders’ programme manager, she realized that she has the opportunity to use her skills to share the beauty and splendour of nature, while providing insights into the challenges of conservation. “To participate in The Great Elephant Census is a rare gift and a privilege that provides us a chance to paint a clearer picture on how we should focus on progressive solutions to conservation threats”.

KELLY LANDEN threw down an anchor in 2002, abandoning a career on the oceans to dedicate herself to African conservation. Having a passion for wildlife and an affinity for photography, as Elephants Without Borders’ programme manager, she realized that she has the opportunity to use her skills to share the beauty and splendour of nature, while providing insights into the challenges of conservation. “To participate in The Great Elephant Census is a rare gift and a privilege that provides us a chance to paint a clearer picture on how we should focus on progressive solutions to conservation threats”.

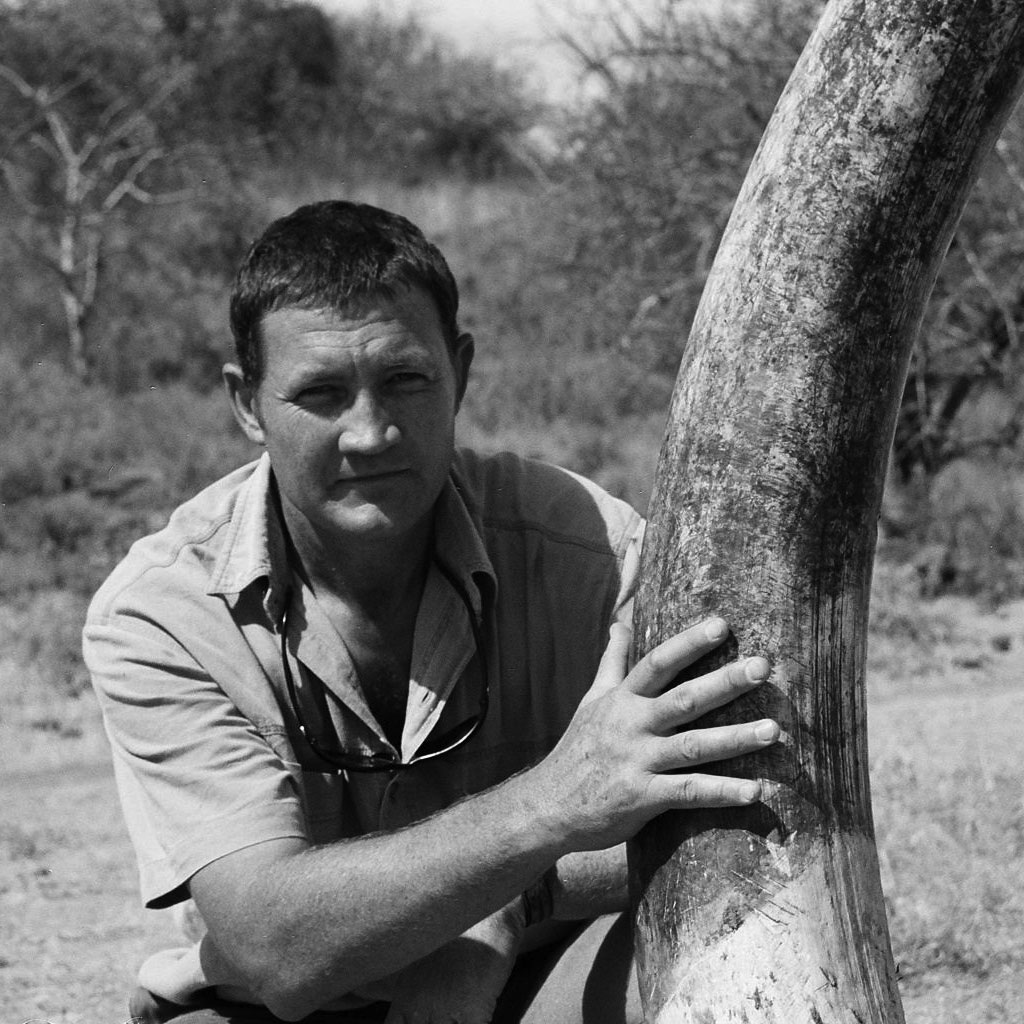

RICHARD MOLLER is one of Kenya’s most respected hands-on conservation project managers. As co-founder of the Tsavo Trust, he supports wildlife, habitat and communities in the greater Tsavo ecosystem, Kenya’s largest protected area and home to most of the world’s surviving ‘hundred pounder tuskers’.

RICHARD MOLLER is one of Kenya’s most respected hands-on conservation project managers. As co-founder of the Tsavo Trust, he supports wildlife, habitat and communities in the greater Tsavo ecosystem, Kenya’s largest protected area and home to most of the world’s surviving ‘hundred pounder tuskers’.

MARK MULLER was born & raised on a Coffee farm on the slopes of Kilimanjaro. He was schooled in Tanzania and Kenya and, immediately after school, came to Maun in Botswana, where he has spent the last 42 years. He has always had a passion for wildlife, with a particular love of elephants and birds. His love of photography was first sparked on a trip to Antarctica in 2006.

MARK MULLER was born & raised on a Coffee farm on the slopes of Kilimanjaro. He was schooled in Tanzania and Kenya and, immediately after school, came to Maun in Botswana, where he has spent the last 42 years. He has always had a passion for wildlife, with a particular love of elephants and birds. His love of photography was first sparked on a trip to Antarctica in 2006.

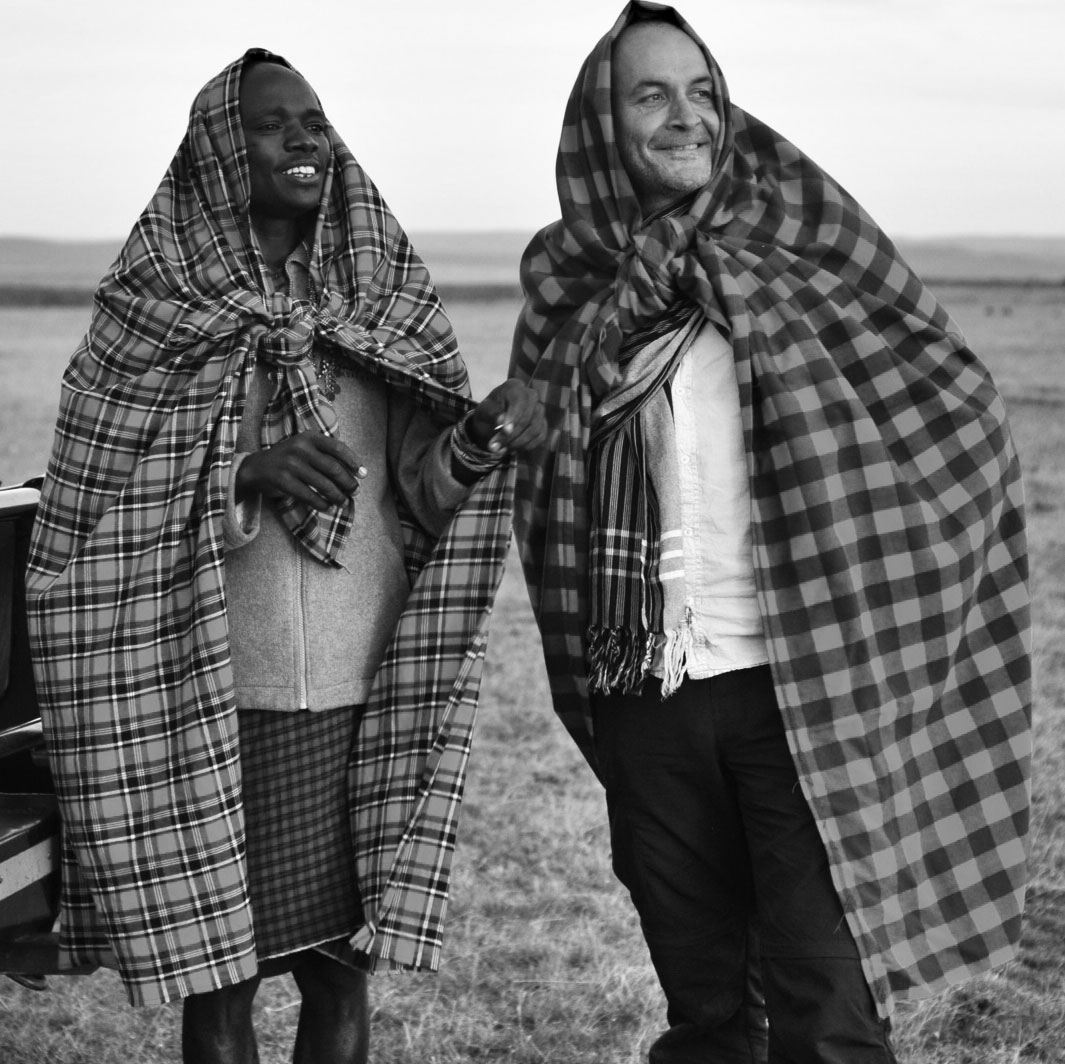

MICHAEL LORENTZ is passionate about wildlife, wilderness and elephants in particular. Born in South Africa, he knew early that his true vision and happiness would lie in Africa’s wild places. A passionate and award-winning photographer, Michael’s work has been featured in several publications, as well as at the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History in Washington DC.

MICHAEL LORENTZ is passionate about wildlife, wilderness and elephants in particular. Born in South Africa, he knew early that his true vision and happiness would lie in Africa’s wild places. A passionate and award-winning photographer, Michael’s work has been featured in several publications, as well as at the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History in Washington DC.

BEN NEALE and KYLIE BERTRAM are the Australian couple behind Gallery Earth. At their core is a deep respect for conservation and a love of adventure. Not everyone has the opportunity to fly or travel, but they believe everyone appreciates and is inspired by the beauty of nature. They aspire to capture this beauty on their journeys, most often suspended beneath the canopy of a paraglider.

BEN NEALE and KYLIE BERTRAM are the Australian couple behind Gallery Earth. At their core is a deep respect for conservation and a love of adventure. Not everyone has the opportunity to fly or travel, but they believe everyone appreciates and is inspired by the beauty of nature. They aspire to capture this beauty on their journeys, most often suspended beneath the canopy of a paraglider.

ANTON CRONE quit the crazy-wonderful world of advertising to travel the world, sometimes working, sometimes drifting. Along the way, he unearthed a passion for Africa’s stories – not the sometimes hysterical news agency headlines we all feed off, but the real stories. Anton strongly empathises with Africa’s people and their need to meet daily requirements, often in remote, environmentally hostile areas cohabitated by Africa’s free-roaming animals.

ANTON CRONE quit the crazy-wonderful world of advertising to travel the world, sometimes working, sometimes drifting. Along the way, he unearthed a passion for Africa’s stories – not the sometimes hysterical news agency headlines we all feed off, but the real stories. Anton strongly empathises with Africa’s people and their need to meet daily requirements, often in remote, environmentally hostile areas cohabitated by Africa’s free-roaming animals.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()