GUEST POST by Nicholas Dyer

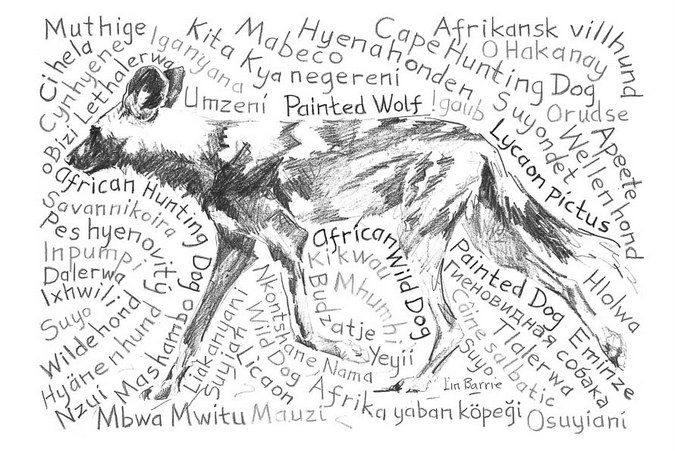

Lycaon pictus has many names in English. Among them are ‘African wild dog’, ‘wild dog’, ‘painted dog’, ‘Cape hunting dog’, ‘African hunting dog’, ‘hyena dog’, ‘ornate wolf’ and ‘painted wolf’.

It seems somewhat ironic that so many names have been given to this creature when so few are left on our planet.

Indeed, some argue vehemently that ‘African wild dog’ is correct and others’ painted dog’, and increasingly the name ‘painted wolf’ has its fans. But are any of these correct, does it matter, and what is the background to Lycaon pictus’ many English names?

To stay on neutral ground (for the moment) I will refer to Lycaon pictus as ‘Lycaon’ throughout this article.

What’s Lycaon?

First, where did Lycaon’s scientific name came from? When Lycaon was first ‘discovered’ in 1820, it was thought to be a type of hyena and given the name Hyaena picta by Dutch zoologist, Coenraad Temminck. But he was wrong.

Seven years later, the British anatomist and naturalist Joshua Brookes established that the animal was a Canid, and Lycaon gained its current scientific name, Lycaon pictus.

These two distinguished gentlemen did not really discover anything, as the Lycaon has been around for longer than we Homo sapiens and they were indeed not the first humans to see them.

The word ‘Lycaon’ has its origins in Greek mythology. Lycaon was the King of Arcadia who decided to test Zeus’ omniscience by serving up the roasted flesh of his son to see if he would notice. Zeus did notice and, understandably annoyed, turned Lycaon into a wolf and restored his son to life.

So the best translation for Lycaon is ‘wolf-like’. And pictus is simply the Latin for ‘painted’. Hence ‘painted wolf.’

Dog or Wolf?

So is Lycaon a dog or a wolf? Well, in fact, it is neither, although one could just about say it is closer to a wolf than a dog. This is because all of our domestic dogs are descendants of the Eurasian wolf (Canis lupus), including our great dane and beloved chihuahua.

From a scientific standpoint, they are all in the same family known as Canidae. Within this, there are two relevant branches (or genus) to look at here – Canis and Lycaon.

In the genus Canis (which means dog in Latin) exist the wolves and their descendants – our domestic dogs. Canis also includes the coyote (Canis latrans), dingo (Canis lupos dingo), and the highly endangered Ethiopian wolf (Canis simensis). And while phylogenetically different, Canis includes all jackals (Canis adustus, aureus and mesomelas).

Meanwhile, our Lycaon pictus is alone in its own genus called… Lycaon. The species is only very distantly related to a wolf or a dog, and there is no chance that you could interbreed a Lycaon and a Canis.

Indeed, while they share many physical characteristics, there are significant differences too. Lycaon only has four toes on its front feet and does not have a dewclaw. Also, its dentition is completely different from a wolf or a dog.

So, to call Lycaon’ dog’ or ‘wolf’ is not correct from the perspective of either taxonomy or phylogenetics.

A History of Hate

Some argue that the name ‘dog’ has been detrimental to the species. For over 100 years, Lycaon has been terribly persecuted by man, reducing their numbers from 500,000 to 6,600 in less than a century.

They were considered vermin by European settlers anxious to recreate their European farming systems across Africa. Ignorant farmers highly exaggerated Lycaon’s threat to livestock and a systematic programme of extermination was carried out through much of southern Africa.

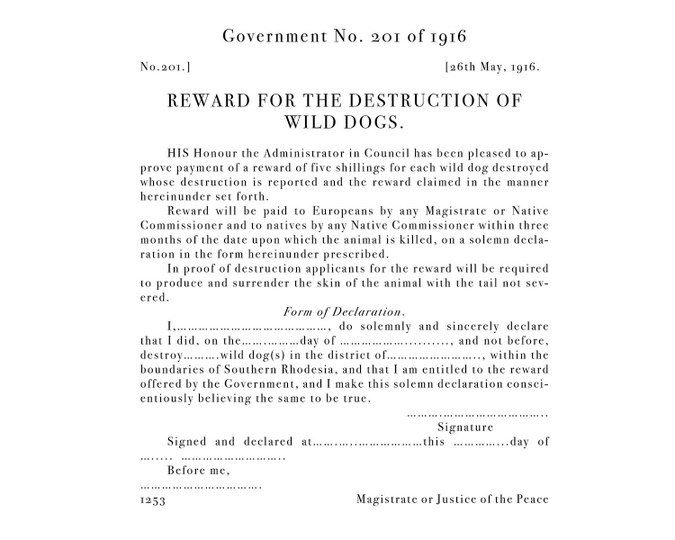

In Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), a five-shilling reward was introduced in 1916 for proof of destroying a Lycaon, and the bounty was increased periodically until it was finally abolished as recently as 1977.

Many argue the name ‘wild dog’ denigrated Lycaon to a dangerous feral animal, a mundane creature of no interest to anybody and certainly not worth conserving. Rhodesian farming journals are littered with suggestions on how best to exterminate the beleaguered creature.

Indeed, when I tell people that I spend most of my time following three packs of ‘wild dogs’ on foot, I am regularly faced with two questions. “What breed of dog is it?” and “Are they mongrels that have escaped from villages and gone wild?” And many of these questions come from people who live in Africa!

Given this, it is understandable why some argue that the name ‘dog’ has played its part in hastening them towards extinction.

A Rebrand?

In many ways, Lycaon has already gone through a rebrand. From being considered vermin, a small but increasing number of people are getting to know the species, and while not yet up there with the Big 5, Lycaon is among the top attractions for safari-goers.

And these new aficionados see them for what they are. Fantastic hunters, yes, but more importantly, incredibly social animals that demonstrate fun and loving interactions inside their intricate packs.

From my past career in marketing, I ask myself whether the word ‘wolf’ would be more appealing to the millions yet to discover them and would this, in turn, support their conservation?

There is undoubtedly a considerable revival across Europe and America supporting the conservation of their native wolves. Increasingly, they are no longer demonised but better understood and welcomed as Europe and America’ re-wild’. Could the rapidly improving associations around the name ‘wolf’ help Lycaon?

I am not the only person to think so. Sir Richard Branson recently wrote about Lycaon:

“One of the reasons their numbers plummeted alarmingly was because people thought of them as vermin. They were known as wild dogs, and this name helped to cast a negative light on them.

“As somebody who has always been interested in branding and marketing, if we could get everybody to call them painted wolves, it would make quite the difference to their reputation, and therefore their survival. Many people have begun to realise the beauty of them, and their numbers have grown back. Long may it continue.”

Sir Richard Branson

Nov 2016

Past Success

The erstwhile named simian fox (Canis semensis) was also known as the simian jackal, red fox, Abyssinian wolf and Abyssinian dog. It faces similar threats to Lycaon and is Africa’s most endangered carnivore. In this case, the much closer genetic relationship to domestic dogs increased the risks of hybridisation as there has been clear evidence of interbreeding between the species.

A concerted effort to ‘re-brand’ the creature to the ‘Ethiopian wolf’ has played a significant role in bringing this beleaguered creature to the world’s attention and improving support from conservationists and researchers alike.

Somehow, the name ‘wolf’ conjures something more special, wild and vulnerable than ‘dog’.

The Attenborough Effect

In Sir David Attenborough’s new epic documentary series Dynasties, the BBC spent two years filming Lycaon in Mana Pools National Park in Zimbabwe. Their film features the same packs that are in my book Painted Wolves: A Wild Dog’s Life. I spent many days and hours photographing Lycaon alongside the talented BBC team.

I also spent many hours discussing Lycaon’s name with the film’s producer, Nick Lyon. To us, it became apparent that choosing the name ‘painted wolf’ had considerable advantages, having quietly debated many of the arguments in front of our cameras and peacefully sleeping Lycaon.

This is not the same as trying to rename the lion or the elephant. Painted wolf is already one of the many accepted English names for Lycaon. And we should recognise that this creature is almost totally unknown by any name in the wider world, barring a small band of safari-goers and conservationists.

The BBC is now about to bring this incredible creature into the living rooms of an estimated billion people who don’t know they exist, let alone what they should be called. But they are about to discover them and fall in love with them as the ‘painted wolf’.

What’s the Objection?

Perhaps what is most surprising to me is the reaction I get when I call Lycaon the painted wolf. It ranges from “It’s not a wolf, it’s a dog!” to the furious, adamant and hostile. More mentally agile people are interested in the reasons and happy to engage in the debate with their points of view.

Scientists and conservationists legitimately worry that fragmenting the name undermines their efforts to increase awareness of the species and raise funds for research and conservation. This fear is very understandable. They have put in a lot of time and effort to build awareness of the species, and their concerns should be respected.

Yet, here again, there is no unanimous agreement. On one side, some feel everyone has settled on ‘African wild dog’ as the correct name. Yet there are others, who would insist that the name is and should be ‘painted dog.’

So to claim, as some might, that there exists a unanimously agreed English name for Lycaon is not correct. While I believe there are strong arguments for using ‘painted wolf’ as a legitimate alternative, I also accept that it is vitally important to link this name to what scientists and conservationists prefer to call them; whether wild or painted dog.

Conservation Opportunity

Regardless of everyone’s views, the reality is that Sir David Attenborough, beloved and trusted worldwide, will enter people’s homes in just under two weeks and call these creatures’ painted wolves.’ He will reach a substantial worldwide audience previously oblivious to their existence.

This is one reason why I have formed the Painted Wolf Foundation together with the well-known Lycaon conservationist Peter Blinston and leading African wildlife conservationist Diane Skinner.

Peter runs the well-established and respected Painted Dog Conservation, responsible for Lycaon’s welfare in Hwange and Mana Pools National Parks in Zimbabwe. He is also the co-author of our book Painted Wolves: A Wild Dog’s Life.

The objective of the Painted Wolf Foundation is to raise the awareness of Lycaon worldwide and raise funds for those organisations working to conserve the species across Africa. There is no universal organisation raising funds or awareness under the banner “Painted Wolf”, and it is a critical opportunity to capture the interest that is building for this neglected Lycaon.

A Success Story

The Painted Wolf Foundation has the support of many’ wild dog’ and ‘painted dog’ conservation organisations who fully understand the rationale of using the painted wolf name, and we hope to support them in turn.

We have also received tremendous help from major wildlife conservation organisations around the world, including WCN, Tusk, the David Shepherd Wildlife Foundation and Virgin Unite. Each provides critical support to Lycaon and don’t refer to them as wolves. But they do understand and support our strategy.

And last year I visited the International Wolf Centre in Minnesota which has embraced our efforts to save their wolves’ distant African cousins, and they have used their substantial networks to promote our work and raise Lycaon’s awareness.

So far, our efforts have raised a total of US$200,000 using the painted wolf name. We do not intend to cannibalise donations from existing wild and painted dog donors, but know that we can find new support from those who fall in love with this creature thanks to our awareness programme, my articles and pictures, our book and of course the BBC film.

What’s Important

As far as we are concerned at the Painted Wolf Foundation, we are not DOGmatic about what people choose to call Lycaon, but we have firmly sided with the name painted wolf for all the reasons discussed. Indeed, Painted Dog Conservation is not going to rebrand, and neither is the African Wildlife Conservation Fund going to stop calling them African wild dogs. Yet we can, and do, all work well together.

This is because we all recognise that the threat to Lycaon is serious and goes well beyond what people call them. Snaring, disease, road kills and shrinking rangelands are Lycaon’s real threats. Their name is at best, a side-show.

The Painted Wolf Foundation has a primary aim – to put Lycaon on the top table of conservation along with the elephant, rhino and lion. It’s where they belong, and the name that’s on their invite is our least concern.

Final Thought

Finally, it should also be remembered that this whole debate is what we call them in English. The Germans and Dutch call them ‘hyena hounds’ while the French and Spanish refer to them as Lycaon.

And let’s not forget the multiple names they have in local African languages whose names for Lycaon go back to before we English speakers even knew that they existed. This concept has been beautifully illustrated in Lin Barrie’s incredible work of art, “What’s in a name?…”

And to complete Juliet’s quote from Shakespeare’s play: “…that which we call a rose by any other name would smell as sweet.”

Not that I have ever come across a sweet-smelling painted wolf.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()