Close encounters with Africa’s megafauna are an irresistible magnet for many tourists in Africa, and for some, the closer the encounter, the greater the thrill. Walking with lions is now a popular tourism activity.

So when a tourism operator offers the chance, for a fee, to ‘walk with lions’, it is no surprise that there is a steady flow of punters eager to do it. And when it is claimed that the money goes towards an elaborate project purporting to rewild lions, it seems, superficially at least, to be a Good Thing.

After all, Africa’s wild lion population is in bad shape. A half-century ago, some 100,000 lions ranged across Africa’s savannas, but lion habitat is only a quarter of what it was then, and today lion numbers are fewer than 30,000. Forty per cent of these live in Tanzania, and only nine countries can claim to have more than 1,000 wild living lions. To say that lions in the wild are on a one-way ticket to extinction is arguably no overstatement. So, where could there be a problem with any attempt to reverse the trend?

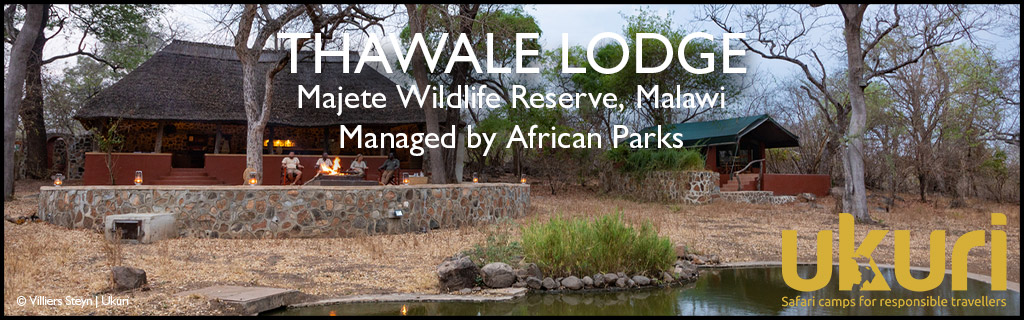

Well, controversy and conservation are well-acquainted and pretty well constant companions. And around the operations of Antelope Park in Gweru, Zimbabwe, and their sister operations called Lion Encounter at Victoria Falls in Zimbabwe and Zambia, where ‘hands-on’ interaction with these great felines is promoted, the controversy is well and truly raging. Walking with lions is their major tourist attraction – and questions are being asked about how lions are sourced and where they disappear to when too big to walk with humans.

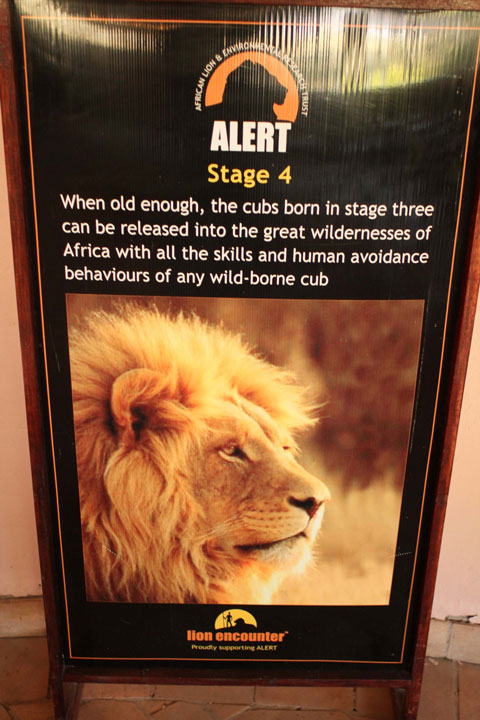

Antelope Park, as stated on its website, is “home to the world-famous ALERT lion rehabilitation programme, as seen in the major UK TV documentary series Lion Country.” ALERT, it would seem, is the umbrella organisation in a network of subgroups: ALERT is a non-profit body, but the subgroups are not.

The nub of the issue is the ALERT’ vision’, which is founded on a four-stage rewilding strategy, with stage four being the successful release of lions into true conservation areas. One understands that grand ideas are not always realised overnight, but ALERT was founded in 2005 and has yet to release any lions into the wild. But lions, true to the basic strategy of all life, reproduce. Cubs taken from their pride groups to walk with tourists soon outgrow their purpose and are moved up a stage, and ‘new’ walking specimens are brought in. The lions in the middle stages of the rehabilitation model will mature and will breed. And as the breeding cycle continues, the number of contained lions grows. Unless lions are legally released into a wild area, the ‘captive’ population has to balloon. It’s simple arithmetic. Figures provided to Africa Geographic by ALERT show a significant build-up of baby lions (where the money is made), a significant death rate in the middle stages and no successful final stage releases to date. After eight years, those numbers speak for themselves. And yet ALERT persists with its conservation claims, and volunteers and tourists flock to their operations. Let me be clear on this; I am all for successful tourism operations – but not when they redirect money from genuine conservation activities and not when the promises of conservation impact are nothing more than a thin marketing veneer.

The ‘excess’ lions from these breeding operations will have to go somewhere to relieve the bottleneck, and if that destination is not a legitimate conservation area, where will that somewhere be?

The fear and, in some quarters, strongly held suspicion is that via some form of wildlife laundering system lions will find their way into one or more of the many lion breeding farms that serve canned lion hunting operations.

This would certainly not be conservation in any shape or form. In fact, it would mean quite cynically that conservation money from volunteer internships, fees to walk with lions and donations is being diverted from excellent conservation projects into operations of questionable ethical standing.

If this is not the case, then only complete transparency and accountability for all the lions involved from cradle to grave will allay the growing disquiet of the conservation world. And even if such transparency is forthcoming, is it, in the first place, sensible to offer ultra-close encounters with big, dangerous animals? Attacks on humans and maulings have already occurred at Lion Encounter, and quite possibly, a real tragedy awaits. But that is another story.

I asked Dereck Joubert, conservationist, National Geographic Explorer in Residence and wildlife documentary filmmaker extraordinaire for his views, so I sign off with his wise words:

“There has been a proliferation of these walking with lions operations, not just in Africa. I also saw them in Mauritius. In my opinion, the activity is fundamentally flawed. A lion is a potentially dangerous animal, and walking with it not only exposes guests to an accident that will result in the lion needing to be killed but also erodes the wildness, the mystique and the very essence of what a wild lion is by taming it.

It is the respect for that vitality and wildness that drives our conservation of wild lions. If you consider that there are probably 6,000 lions in captivity but that we never include those lions into the overall figure of between 20,000 and 30,000 in the wild, its because the conservation of lions is not based on the total number of lions there are in the world, but those in the wild. As such, captive lions have little to do with conservation.

The fact that the captive lions simply confuse the conversation about lion conservation is one thing, but I worry about what happens when the lions get old, injured, sick or a little less cute to walk with. Do they feed a canned lion hunting scheme? Probably.

And canned lion hunting is one of the greatest misguided uses of an icon of Africa. It damages the reputation of South Africa, it is spurred by greed alone, and it has stimulated a market that could be responsible for the collapse of not just wild lions but tigers as well, via its evil cousin the bone trade.”

All photos were taken by an Africa Geographic representative on assignment.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()