Trophy hunting is often the subject of heated debates. The hunting of predators is a particularly sensitive topic, often described as a cruel, needless practice that has no conservation value for the species concerned. Trophy hunters, on the other hand, claim that hunting predators is an essential part of conservation outside of national parks.

Here then, is an example of how trophy hunting can be of benefit to conservation if formulated properly and managed strictly. The notes in this blog post refer to a particular area in Namibia (Kunene) and do not speak to trophy hunting operations elsewhere.

As with most hotly contested issues, trophy hunting is more complex than it first appears.

Typically, two main questions regarding trophy hunting arise: 1) is trophy hunting beneficial for conservation? 2) Is it providing substantial benefits for local people? I believe that the Namibian government has a good trophy hunting system in place, which keeps corruption to a minimum and provides direct benefits to local people. I therefore use the Namibian system as an example of how trophy hunting can benefit conservation and local communities in Africa.

There are two distinct types of farmland in Namibia – communal and commercial farms. In the commercial farming areas, land is parceled up into privately owned farms that may be used for livestock, game farming, hunting or ecotourism. In the communal areas, the land is owned by the state, but inhabited by people who farm with cattle, sheep and goats. Although trophy hunting on commercial farms in Namibia is worthy of consideration as part of the hunting debate, I will focus here on communal farmlands.

Although Namibia is currently hailed as an outstanding example of conservation in Africa, this was not always the case. In the 1980s, illegal hunting by foreigners and locals was rife in the communal lands now known as the Kunene and Caprivi/Zambezi regions. Poaching was rife, and the very idea of conservation was met with hostility, as it was seen as yet another means of oppression by the apartheid government.

This situation changed with new legislation by the independent Namibian government in 1996. The essence of this legislation was to give Namibians living in communal areas rights to utilise their wildlife sustainably and to benefit directly from ecotourism in their regions. The main prerequisite for these rights was that the people formed local institutions to manage and conserve wildlife within self-defined areas; these institutions are known as conservancies. Democratically elected committees run the conservancies to manage the wildlife and money from wildlife-related activities within their boundaries. Through their conservancies, local people can now charge trophy hunters and ecotourism operators for using the peoples’ natural resources.

Today, community conservation in Namibia can be compared to a three-legged pot (or ‘potjie’), which has three supporting ‘legs’. These legs are local ownership, ecotourism and sustainable use. Local ownership of wildlife is the most important of these legs, providing the foundation for the other two legs. Ecotourism and sustainable use (including, but not limited to, trophy hunting) are the two main income-generating avenues for Kunene conservancies. The relative importance of these two legs varies from one conservancy to another.

Three of the five conservancies in the southern Kunene sub-region, with whom I work closely, have a stable income from hunting and ecotourism; the fourth relies only on hunting, and the fifth relies solely on ecotourism. The first three indicated that roughly one-third of their income (R120 000-150 000 per year) is derived from trophy hunting, the rest coming from ecotourism and other forms of wildlife hunting (e.g. for meat). Together, these conservancies manage 10 835 km2, home to approximately 5 900 people.

The conservancy which currently relies exclusively on trophy hunting generates R100 000 annually but is in the process of building an ecotourism lodge to increase its income-generating potential. One of the main reasons this conservancy has been slow to realise its ecotourism potential is that it is not as scenic as the other conservancies in the region. Thus, investors have started with the more spectacular conservancies, leaving this one to depend on hunting. Without trophy hunting, this conservancy – covering 2 290 km2, home to 1 300 people – would simply not exist.

Finally, one conservancy has chosen to rely solely on income from ecotourism and not to allow any kind of hunting in their area. The reasons for this decision are multiple, but it is important to note that the local people decided to use only ecotourism. This is the smallest of the five conservancies (286 km2, home to 230 people), yet it is a hotspot for ecotourism, as it has a famous rock art site within its boundary. Several lodges and a campsite operate within this relatively small area, and there is simply not enough space to include trophy hunting – most eco-tourists do not appreciate gunshots! Simply put, it made more sense for this conservancy to rely on ecotourism alone.

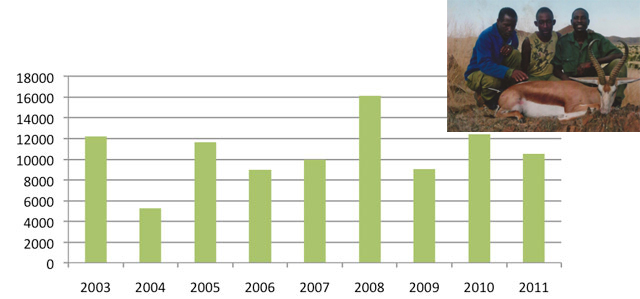

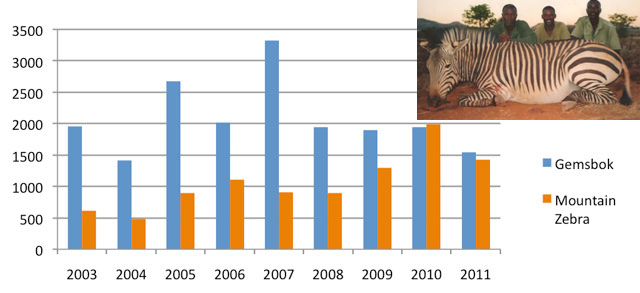

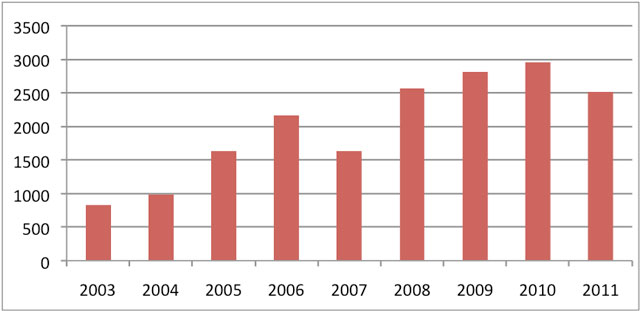

The main species hunted in all conservancies are antelope. As illogical as it may sound, allowing conservancies to kill antelope has been the primary reason for the recent increase in the range and population numbers of antelope species in the region. Hunting in the Kunene region has shifted from being an uncontrolled, illegal past-time for many local people to being a controlled, legal form of income generation from a small number of foreign hunters. After recovering from severe drought and intense poaching in the 1980s, wildlife populations increased and started stabilising after the establishment of communal conservancies. From 2003-2011, annual road-based game counts have shown that the main prey species in the Kunene region (springbok, gemsbok and mountain zebra) have either maintained their population numbers or increased.

Each conservancy is granted a hunting quota of game animals by the government; they then reach a bilateral agreement with a trophy-hunting operator. In this agreement, the trophy hunter agrees to pay a certain amount for each antelope shot in the conservancy (amongst other conditions). The conservancy sends one or more of its employees with the hunting operator and client when on safari to ensure that they comply with the terms of the agreement. The conservancy then records the number of animals shot by the hunter and ensures that he pays them for what he shoots and that he does not shoot more than the agreed quota.

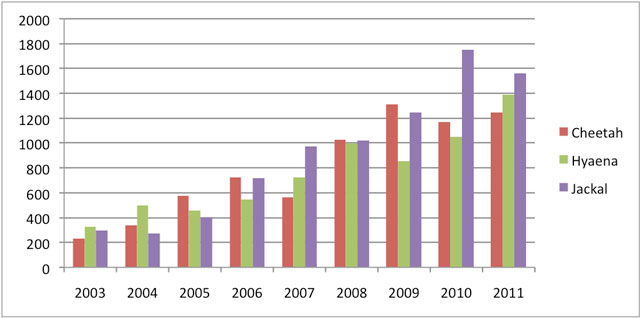

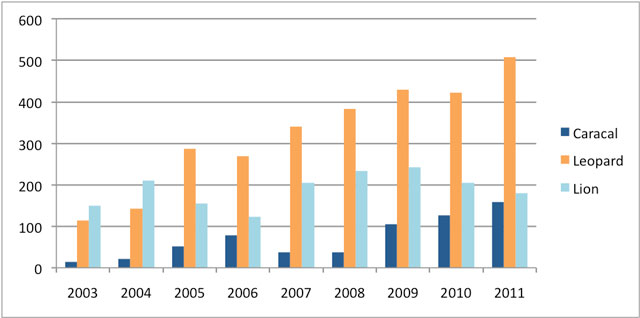

So what does trophy hunting in the context of community conservation mean for conservation, especially for carnivore conservation? As outlined above, controlled trophy hunting of prey species has led to an increase and stabilisation in their populations, which support the predator populations. The lion population, which is well studied and monitored by the Desert Lion Conservation and Research project, has increased from approximately 20 individuals to over 130 during the time that conservancies have operated in the region.

Conservancy game guards regularly patrol their conservancies and report all sightings of predators and incidents of livestock losses to predators. The data they have produced indicate that other predator populations have responded positively to conservation in the Kunene conservancies. Although these data do not indicate absolute numbers of predators, one can confidently say that predator sightings are increasing in the region.

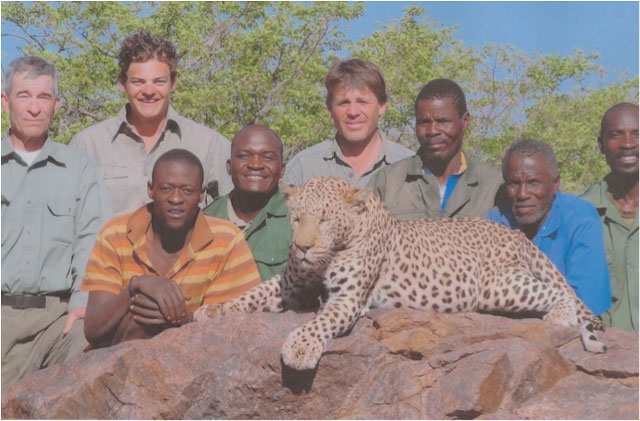

Besides the fact that predators now have more to eat in communal conservancies than previously, they have also been directly conserved through the conservancy system. Conservancies are allowed to sell a limited number of predator species as trophies each year, with the quota once again determined by the government. Two of the abovementioned conservancies support lion populations and may thus be granted one lion as a trophy per year. Trophy hunters pay US$ 8000 and US$ 9000 per lion, per their agreements with the respective conservancies. Similarly, four conservancies charge their hunters US$ 2000 – US$ 4000 for a leopard and US$ 1300 – US$ 2000 for a cheetah. These two species are not always successfully hunted, so there may be several years where no leopards or cheetahs are shot in these conservancies, even though they are provided quotas for them.

Trophy hunting carnivores is more complex than hunting their prey species, and it may be argued that the species considered above are worth more than the ‘price tag’ they are given by trophy hunting. Carnivore populations are also sensitive to overhunting and may thus decline if trophy hunting is not strictly controlled and monitored. However, the situation with carnivores is further complicated by human-predator conflict. As most of the conservancies’ occupants are livestock farmers, the presence of a healthy predator population represents the potential for loss of income. Conservancies in the Kunene region have reported increasing livestock losses, which match the increase of predators shown above.

In two conservancies, I investigated the livestock losses in more detail for 2010-2012. Farmers lost livestock (cattle, donkeys, horses, sheep and goats) to the value of N$ 91 000 per year in one conservancy and N$ 196 600 per year in the other. Both conservancies support the full gamut of predator species (i.e. all cat species, hyenas, jackals and baboons). They have thus occasionally sold lion, leopard and cheetah to their respective trophy hunters. The fact that these predators have a direct value is thus a primary argument that conservancy managers use to pacify their members who regularly lose valuable livestock to these species. Furthermore, the value given to predators by trophy hunters is much easier to explain to local farmers than the nebulous concept that eco-tourists enjoy seeing these species.

Although the value of lions as trophies is an important argument for their conservation, the conservationists in the region are continually working to find other ways to place a tangible value on the species. These ideas include charging tourists to the region per lion sighting and/or employing local people to act as ‘lion guides’. Replacing lion trophy hunting with strategies depending solely on ecotourism may be in the pipeline, but these ideas will only be realised if the ecotourism industry fully supports them. In the meantime, however, we continue to use the lion’s trophy ‘price tag’ as an incentive for their conservation. If a blanket ban were to be placed on hunting the species, or if the hunting market were reduced (i.e. if the U.S.A. places lions on their list of endangered species), we would lose this bargaining chip.

The consequences of not responding to human-predator conflict in an immediate, tangible way can be severe for farmers and predators. Showing that predators have real value to rural livestock farmers is not an easy task, even within a working system. In cases where predators cause severe or continued losses, farmers may destroy the ‘problem animals’ themselves without waiting for government-approved hunting permits. These are lose-lose situations where farmers lose many livestock and predators are destroyed in retaliation, with no financial gain. Curbing the number of these incidents is the real challenge for carnivore conservationists in Africa.

Moving beyond the conservation of carnivores, we must remember that conservancies cover portions of a larger ecosystem. The existence of conservancies means that species such as elephant and rhino threatened with poaching across the rest of Africa find a haven in Namibia. This protection is based entirely on the principle of local ownership – the communities living in conservancies are the legal owners of the wildlife they live with. As legal owners, they can use many species through sustainable trophy hunting. Creating laws that dismiss these ownership rights will undermine the best example of community conservation in Africa.

Also read: A Namibian’s view on hunting in his home country

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()