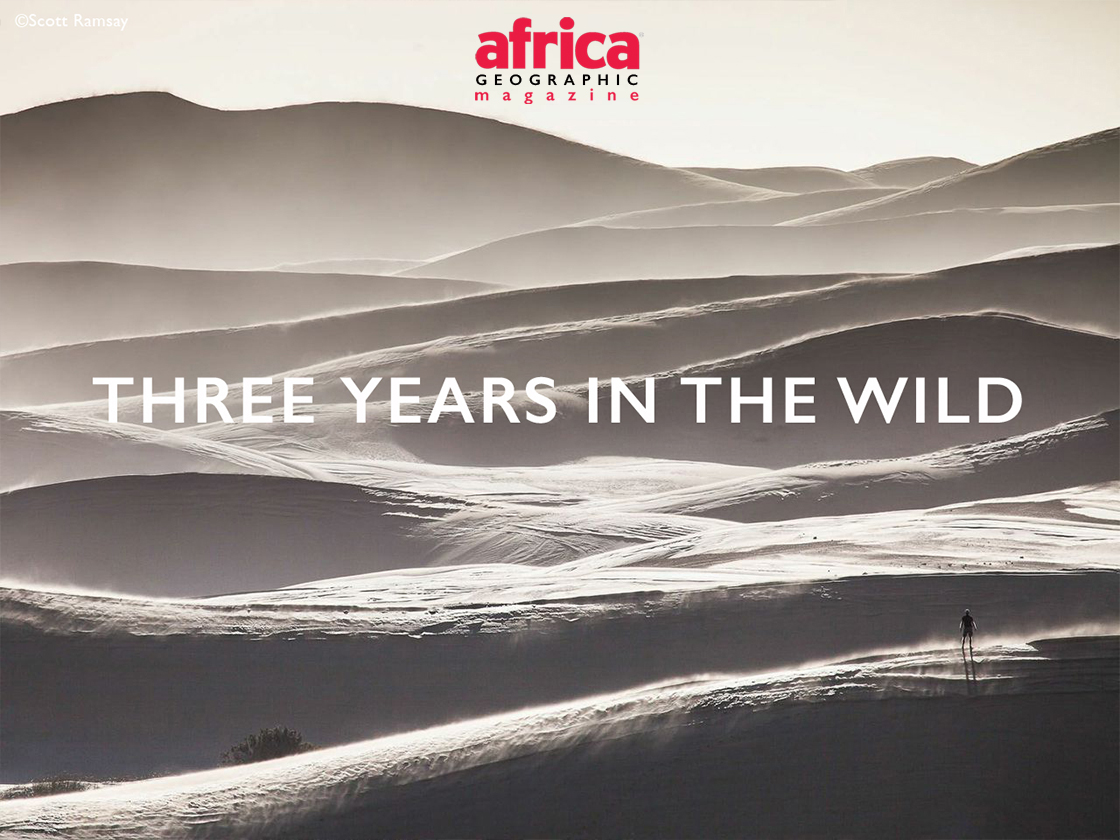

AN OFFICE ESCAPE TURNS INTO A SOUTH AFRICAN ODYSSEY

Sometimes, I feel like I’m the luckiest person in the world. For the past three years, I have lived almost exclusively in South Africa’s national parks and nature reserves.

On a typical day, while some people sit in city traffic, I could photograph lions in the Kalahari, tracking rhinos with rangers or swimming with turtles. My good fortune is made more palpable because I once had an office job, a so-called successful career working in the cities of Johannesburg, Cape Town and London.

But I spent much time staring out the office window, pretending I could see elephants on the horizon. Perhaps it stems from my childhood. My parents regularly took my two sisters and me to the Kruger National Park. At the time, I probably took these family holidays for granted, but many years later, the memories are still clear.

Interestingly, the most visceral reminders of those holidays are not the sight of wild animals but the smells and sounds of the bush – the unmistakable scents that rise from the dry earth after the rain has fallen, the chirruping of woodland kingfishers, the barking of baboons and the rasping grunt of leopards.

I only realised later that, while I enjoy the excitement of cities, I felt most alive and connected to myself when immersed in nature.

While at my desk in Johannesburg, I was conscious that I was just a few hours away from places like Kruger, the Okavango Delta and the Drakensberg mountains. It was infuriating and inspiring in equal measure.

But then, after daydreaming for several years – and no doubt annoying my successive bosses – the little voice in my head became a booming demand I could no longer ignore. So I listened.

I approached South African National Parks and proposed travelling through the country’s most important protected areas for a year. I’d write a blog, take photos and tell the stories of South Africa’s wild places, showing why our national parks and nature reserves are so important, what is being done to protect them, which species are endangered, who the people are that live and work there and what their stories are.

After getting SANParks’ endorsement and working for a year to raise sponsorship to cover the costs, I set off on my “Year in the Wild”. Ford loaned me an Everest 4×4 and other sponsors, like Goodyear and Cape Union Mart, were equally enthusiastic in their support.

wild places transcend social and political divisions

I found that almost everyone I approached believed in supporting conservation and that wild places generally transcend social and political divisions. On top of that, everyone seemed to love a good adventure, and the most common response I got on meeting potential sponsors was, ‘Can we come with you?’

It wasn’t all easy, though. Any wilderness can be a physical test. I’ve sweltered in temperatures of more than 50°C in the Kgalagadi, and I’ve shivered through a few sleepless winter nights in my tent at the top of the Drakensberg escarpment. And the novelty of hiking for days through thick, thorny bushveld wears off pretty quickly, especially when the animals are scarce.

But being in the wilderness is more of an emotional test, especially if you’re alone. You can’t hide from yourself, and at first, I was lonely. But I learned to find companionship in the land and the animals, and I became grateful for the basics: food when I’m hungry, water (or beer!) when I’m thirsty, the shelter of a rooftop tent in a thunderstorm, sunshine on a cold Karoo day, and my own health.

Often I would go to sleep feeling down, but then I’d wake up in the middle of the night and see the blazing stars. Or I’d rise in the morning to the panorama of the Richtersveld or watch elephants walk past my camp.

At these times, when the enormity of wilderness swallowed me up, I could transcend my own personal story. It was in forgetting myself that I was able to find myself. Trust me, a violent Kalahari thunderstorm directly above your tent will quickly put your emotional preoccupations into perspective.

The African wilderness is full of these experiences. Here I found belonging and contentment that eludes me in a city. To me, life makes more sense when viewed through the prism of wilderness. In the wild, I sometimes drift into a meditational state and inadvertently achieve an unexpected mental acuity. Perhaps the wilderness gives space for our thoughts and emotions to expand.

©Scott Ramsay

It wasn’t all deep and serious. After a few days alone, I’d sometimes find myself laughing aloud for no apparent reason. Or I’d talk to the animals. It may seem nuts, but the animals gave me a sense of community.

But I spent time with lots of great people too. It’s one of the reasons I love my work so much. Generally, conservationists, researchers and rangers are deeply connected to the earth. It’s hard work and poorly paid, but they are driven by something more than money and external validation, and I found them inspirational.

People like Sonto Tembe at Ndumo Game Reserve can imitate almost every bird species’ call, giving visitors an unforgettable experience. Or wildlife vet Dave Cooper and his associate Dumisane Zwane, who work countless hours to treat ill or injured animals, including rhinos that poachers have wounded.

I chatted to Nonhle Mbuthuma, an environmental activist who has stood up to politicians and mining corporations on the Eastern Cape’s spectacular Wild Coast.

‘I live in paradise, and it’s a paradise I want my children to inherit one day,’ Nonhle said. ‘We are not against development, but we have the right to say in what kind of development takes place. Open-cast mining will destroy our area, heritage and sense of identity.’

Middle Left: Activist Nonhle Mbuthuma teaches Eastern Cape youngsters.

Middle Right: Vet Dave Cooper and Dumisane Zwane take a break between treating injured animals.

Bottom: Ranger and pilot Lawrence Monro pioneers the aerial anti-poaching program in KwaZulu-Natal.

©Scott Ramsay

Not least is Lawrence Munro, a ranger and pilot who, against considerable odds, pioneered and now leads the aerial anti-poaching teams in KwaZulu-Natal after years of being told that such a service was not required.

In 100 years, people will look back and think of Africa’s conservationists as heroes

These are just five of the people I met who are doing vital work, even if our materialistic society doesn’t value their efforts. I believe that when people look back in a hundred years’ time, they’ll think of Africa’s conservationists as the heroes of this century. Human slavery was once considered acceptable, and when Abraham Lincoln worked to abolish it, many people with vested interests in its continuation railed against its abolition.

Today, everyone knows that slavery is abominable. The emancipation of the environment is this century’s greatest challenge. Still, as with human slavery, many corporations, governments, and individuals have vested interests in the sustained destruction of Africa’s natural heritage. Conservationists today are fighting a similar battle to Lincoln’s. And like society today considers slavery detestable, in the future, we will consider today’s abuse of Africa’s wild as one of the most tragic and loathsome periods of mankind’s history.

My first “Year in the Wild” went so well that it turned into two, and by the end of September this year, I will have completed three years of almost continuous exploration of South Africa’s 40 most special protected areas.

It’s one of the many tragedies of apartheid that so many people in South Africa were denied access to the most beautiful parts of the country for so long. Everyone deserves the right to engage with their natural heritage.

So I consider myself extremely fortunate. Not many people – even within SANParks – have been to all the national parks, and even fewer have been to all the other special protected areas. I have visited them several times, explored them extensively, and slept in wild places that few have ever seen.

Initially, I was happy just to cover my costs and to complete the journey, sharing the inspiration with others through my photos, social media and articles.

But now, my journey has become somewhat of a pilgrimage. I find myself increasingly bonded to the African wilderness and wildlife. These wild places and their animals have become part of who I am and are probably the greatest source of inspiration in my life. They have taught me that nature is far more important than I ever imagined and that humans need both wilderness and wildlife to live a full, rich life.

South African filmmaker and photographer Craig Foster, who has worked a lot with Bushmen, wrote, ‘It seems like our bond with animals is deeply rooted in our psyches, and we need them just as much as we need wild open spaces. We don’t need them just because they are pleasant – we need them for psychological survival. At a deep level, a land without life, without creatures, is disturbing.’

After three years, I find myself even more determined to make others aware of Africa’s natural treasures. My journey started out as a dream, an adventure, but it has become my vocation.

I’m sure that if other people – especially those in business and government – can see for themselves what I have seen, then they too will be inspired to care more for the few pockets of wilderness that remain.

Contributor

Scott Ramsay is still out there somewhere. But he’s not hiding. Through his work, Scott hopes to inspire others to travel to the continent’s national parks, and nature reserves, which Scott believes are Africa’s greatest assets and deserve to be protected at any cost, not only for their sake but for our own survival. His one-year journey to explore South Africa’s wild places turned into three. Perhaps as the wild places beyond South Africa’s borders lure him, the journey will continue for many years.

Scott Ramsay is still out there somewhere. But he’s not hiding. Through his work, Scott hopes to inspire others to travel to the continent’s national parks, and nature reserves, which Scott believes are Africa’s greatest assets and deserve to be protected at any cost, not only for their sake but for our own survival. His one-year journey to explore South Africa’s wild places turned into three. Perhaps as the wild places beyond South Africa’s borders lure him, the journey will continue for many years.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()