Fantastic beasts and where to find them

From the despotic Napolean and arachnophile Wilbur to timid Piglet and hardworking sheep-pig Babe, suids (pigs) feature prominently in literature and popular culture. This is perhaps unsurprising given that the domestic pig is one of the most numerous large animals on the planet. However, there are also at least 18 wild species in the Suidae family (depending on the taxonomist), indigenous to Europe, Asia, and Africa. Of these, six species of wild pigs are found on the African continent, rooting their way across savannahs, lurking along dark forest paths, and enjoying a mud wallow as much as the next pig – these are the wild pigs of Africa.

The warthogs (Phacochoerus africanus and Phacochoerus aeithiopicus)

With their wide distribution and diurnal habits (and iconic vocals of a free-spirited, animated representative), warthogs are undoubtedly the most famous of all of Africa’s suids, often spotted on the quintessential African safari. These hardy animals are ubiquitous across savannahs, and almost any safari is all but guaranteed to yield at least one sighting. Unbeknownst to most, there are two species of warthogs roaming the continent – the common warthog (Phacochoerus africanus) spread throughout much of sub-Saharan Africa and the desert warthog (Phacochoerus aeithiopicus), which is isolated to the Horn of Africa.

Adult warthogs attain a size of around 75kg when fully grown, though mature males may weigh as much as 150kg. Their grey, wrinkled skin is covered by a spare smattering of coarse hair and the characteristic facial “warts” (actually just outgrowths of thick skin) for which they are named are particularly well-developed in boars, often extending as much as 15cm from below their eyes. The tusks of the males are also usually longer than those of the females. These modified canine teeth exist in pairs – the impressive upper maxillary pair and the shorter but razor-sharp mandibular pair. Though built a bit like tanks, warthogs display an astonishing turn of speed when necessary, and if flight fails, the tusks can be utilised as deadly weapons in a fight.

Like most species, warthogs subsist on a primarily herbivorous diet, using their specialised snouts to shovel the juiciest bulbs and roots. However, they will supplement this carbohydrate-heavy fare with insects, eggs and even carrion on occasion. After a day foraging, they retreat to underground burrows to pass the dangerous hours of darkness. Boars in their prime are usually solitary (except during the short, fierce breeding season), but females remain in small natal sounders and will care for each other’s piglets.

The other wild pigs

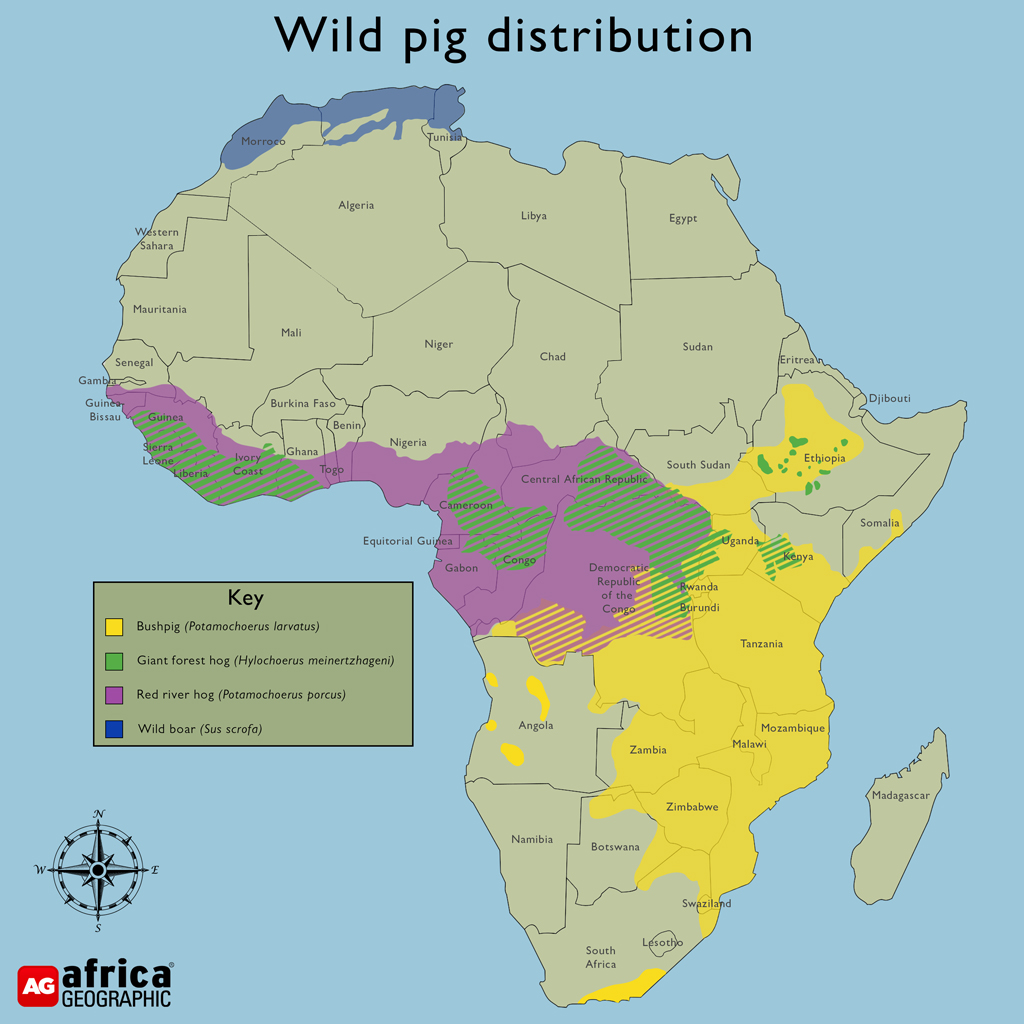

Four additional species of wild pigs prominently found in Africa are the bushpig, red river hog, giant forest hog, and the African subspecies of the Eurasian wild boar – the North African boar.

The bushpig (Potamochoerus larvatus)

The stocky, shaggy bushpig overlaps considerably with the distribution of its distant cousin, the warthog. However, in contrast, few safari-goers ever glimpse these shy animals. Their evasion can be partly explained by their predominantly nocturnal habits, but, in truth, despite their reputation as “aggressive” and “dangerous” animals, bushpigs are usually extremely wary of humans and avoid them where possible.

Though roughly the same average mass as warthogs, this is where the physical similarities between the two pigs end. Bushpigs are covered in a thick, bristly coat that can vary in colour from a reddish-brown to dark grey, often with a lighter underbelly and a white mane. Their eyes are tiny, and the tusks are all but hidden beneath the thick skin of the snout (though they are still present and capable of inflicting considerable damage). Bizarrely, despite significant and apparent differences, warthogs and bushpigs were considered the same species for most of the 20th century and bushpigs only attained species status in the early 90s.

As the name implies, bushpigs prefer dense vegetation and are often found in thickets, forests, swampland or riverine areas. However, they are adaptable and will readily occupy disturbed habitats around agricultural areas, often to the dis”grunt”lement of the neighbouring farmers. Like warthogs, bushpigs rely heavily on plant matter for sustenance, and their status as crop pests is often well-deserved as they have a taste for anything from sugarcane and maize to sweet potatoes and carrots. However, their omnivorous palate is also highly developed, favouring eggs, fledgling birds and carrion in any state of decay. They have even been observed stalking and killing young antelope.

Bushpigs are social animals and live in breeding sounders of up to 12 or more members. The dominant individuals, especially the boars, are very defensive of their sounders and intruders (including two-legged ones) will be chased away at considerable speed.

Red river hog (Potamochoerus porcus)

A close relative of the bushpig, red river hogs (pictured in this story’s cover image) are found primarily in the rainforests of West and Central Africa and are perhaps the most winsome of all Africa’s porcine offerings. They are covered by a luxurious pelt of ochre-coloured fur, which contrasts dramatically with their black and white markings. The comically over-large ears end in long, thin tufts outlined by a shock of white hair. These curl at the tips, giving the impression that the hogs have donned the African equivalent of a court jester’s hat. In contrast, the tiny piglets are decorated with a delicate pattern of pale stripes and spots.

Their diet and social structure are similar to that of the bushpig, and they communicate continuously with other members of the sounder with a vast repertoire of grunts and squeals. Though primarily nocturnal, they may emerge to forage and wallow around water points during the day. The forest baïs of Odzala-Kokoua National Park in the Republic of the Congo are among some of the best places to encounter them in the wild.

Giant forest hog (Hylochoerus meinertzhageni)

In terms of averages, the giant forest hog is considered the largest of all living wild pigs but is also one of the world’s most mysterious. Like the red river hogs, they lurk in the depths of the thick forests in West and Central Africa. Despite their intimidating size and Gothic covering of jet-black fur, giant forest hogs are exceptionally retiring. They are seldom encountered in the wild, even by those who research their habits.

Consequently, there is still much more to learn about this porcine colossus, from subspecies (or even species) distinctions to conservation status. We know they live in family groups, and these sounders include a dominant boar that plays a hands-on (hoof-on?) role in protecting offspring. There is also a strong suspicion that the giant forest hog may be more threatened than its IUCN Red List status of “least concern” implies due to snaring and bushmeat poaching.

Eurasian wild pig/wild boar (Sus scrofa)

As the ancestor of most domestic pig breeds, the Eurasian wild pig or wild boar is a relatively well-known species (though one was somehow mistaken for an escaped lion in Berlin in mid-2023!). These dishevelled beasts are widespread across most of Europe and Asia and have been introduced to North America and Australasia (where they have become a problem in some areas). The African subspecies – the North African boar (Sus scrofa algira – also called the Barbary wild boar) – is smaller than its European relatives and is found in Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()