Protecting nature by following in the footsteps of the San

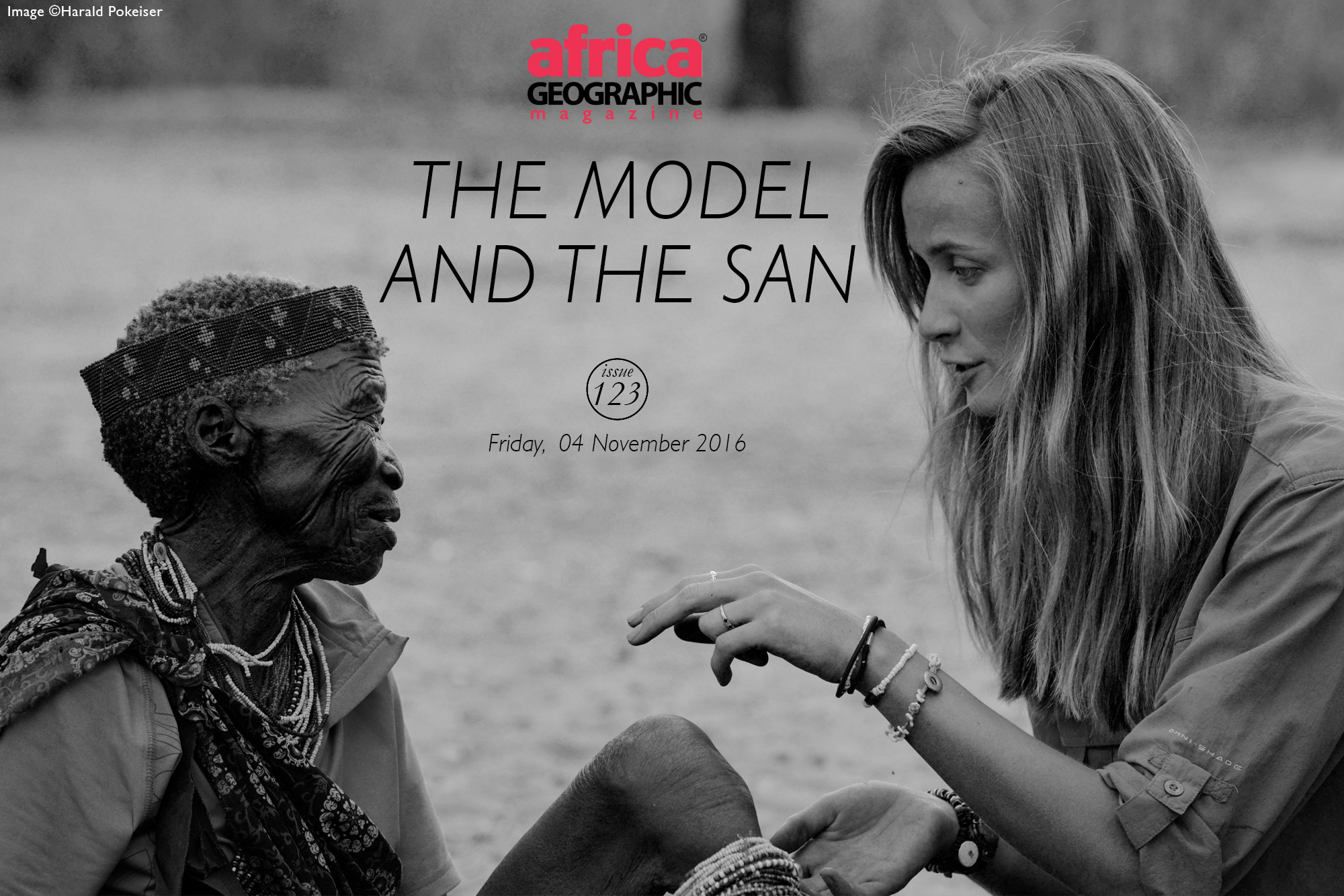

After working for many years as a model and actress in Paris and New York, Aleksandra encountered the San people of Namibia on her travels, and initially thought she needed to ‘save’ them. However, after sitting down and talking to them, she realised that the opposite had happened.

How can I begin to tell the story of the Ju/’Hoansi-San people? There are so many stories to tell, and they are the original storytellers. They have hunted and gathered for centuries, and they have left a long legacy of taking responsibility for the natural world around them, which they understand to be their provider.

The San have always been survivors who adapt against the odds, and perhaps this is partly due to their exemplary ethos of sharing everything they have with each other. For they believe that if we share, we will have enough.

The Ju/’Hoansi-San people of the Nyae Nyae

The country that we now call Namibia was settled by hunter-gatherers at least 100,000 years ago. This may have only recently been proven by scientists thanks to archaeological discoveries, but the few hunter-gatherers that remain have always been aware of their ancestry. Now known as bushmen or the San, their ancestors were Namibia’s very first citizens, and they are part of one of the oldest tribes on Earth. Experts say we can still find traces of the earliest relatives of modern man in their genes.

Most people have heard of the Maasais, the Zulus, and many other indigenous groups across Africa but, for some reason, the San are often overlooked. Perhaps some people prefer to forget that the San were once classified as animals; that they were showcased in museums; that they were hunted for sport, trapped and abused.

2,300 Ju/’Hoansi-San are living in the Nyae Nyae Conservancy – a semi-desert region covered by thorn bush that is located in part of an area, formerly known as Bushmanland, that was used to segregate ethnic groups during Apartheid.

Due to a rapidly developing world, today the San are arguably considered to be the most marginalised group in Southern Africa and are squeezed into 10% of their former territory. They live in extreme poverty and have been forced away from their original lands as a result of illegal land grabbing, leaving the San unable to survive in their traditional way. It used to be easy for the San women to gather when they could move from place to place, but nowadays the resources in their area do not have enough time to replenish, and the community is in competition with the elephants over the little food that is available. As a result, food security is generally quite low in San communities, and not many youths gain a basic education, so illiteracy and unemployment rates are very high.

The majority of the children living in this isolated region don’t have a bright future, and the health status of the San is undoubtedly linked to their low socio-economic status, as their life expectancy – at just 48 years – is 22% lower than the national average. These may all be sad facts, but the San are not unhappy people. On the contrary, they are great, and I feel lucky to learn from them.

If you are someone who adds baobab powder to your smoothie, follows a Banting diet, or tries to focus more on the now and to own less, then you are already following in the footsteps of the San without even necessarily knowing it. Ancient knowledge is catching up with us in a modern context, and there is a reverse trend towards a simpler way of life. But the San are already experts in this field.

A barefoot solution

When I first went to Africa, I was like many travellers in that I wanted to help. But when I met the San people, I realised that the opposite had happened. They had saved me from my poverty of perception and opened my eyes to how much we can all teach each other. What they may lack in material wealth, they more than make up for in richness of spirit.

I started to realise that the western perception of Africa is creating more limitations than possibilities. For many years westerners have been arrogantly trying to change people’s lives without actually including them in the decision-making process.

This inspired me to upgrade the traditional outreach approach to encourage inter-dependency so that both parties give and receive. We need knowledge exchange and communication to all be able to live happily in this world, and everyone needs to teach and be taught.

Cultural tourism involves profiting from indigenous communities by offering tourists a chance to see how the locals live. However, in many cases, the tour operators are getting richer from this initiative, while the local people and their culture is becoming poorer. If cultural tourism is the only future that awaits, it’s understandable why school drop-out rates and alcohol abuse is rife in some indigenous communities.

However, there are ways to share the stories, dreams, ideas and experiences of African tribes without compromising their lifestyle or pride. At Nanofasa Conservation Trust, we believe that ancient knowledge can create modern-day work opportunities. Nanofasa is a non-profit trust in Namibia that was established in Norway in 2011, and that aims to empower the ancient San communities living next to conservation areas to protect wildlife while maintaining and celebrating their culture.

Nanofasa means ‘nature never jumps’ and, together with the San people, the organisation works to ensure healthy and productive interactions between nature, culture and communities to conserve biodiversity and ecosystems for a sustainable future.

The Chinese proverb goes: “Give a man a fish, and you feed him for a day; teach him how to fish, and you feed him for a lifetime.” However, what happens if you do not need to teach a man a skill because he has all the skills he needed for thousands of years until modernity took away many of his possibilities to live off the land? Give a man a job he does not like, and there will be little success. However, if you give him the resources he needs to make his skills and knowledge useful again, you then have a sustainable model at hand.

Nanofasa provides San people with the opportunity to become qualified trackers, traditional teachers, guides, and botanists, then assist the Nanofasa research team in ensuring that their surrounding environment thrives. The San people have passed invaluable skills from generation to generation, and Nanofasa’s Barefoot Academy empowers individuals in their area of expertise.

The moral of the story

The Ju/’Hoansi-San have shown me that nature needs people and that people need nature. Their intrinsic understanding of this symbiosis is why we decided to run Nanofasa based on a model where the San are responsible for leading the way to sustainability.

For real development to take place, we need to nurture, protect and preserve not only our natural environment and wildlife but also our people, their culture and customs. Local communities are the key to a sustainable future. Nanofasa wishes to assist in the battle against poverty and discrimination by facilitating projects that are initiated by the San communities, grounded in their participation and driven forward by the local people themselves.

We need to start working with communities and natural areas within Africa that have stories to tell – stories that will make outsiders want to contribute. We do not have to sell Africa and all its contents; we can tell its stories so that they can continue to be written for generations to come.

We can switch our phones to silent, rewild our perceptions and roar together as one. The tracks are already there, but we have to read them and choose which direction to take. And I choose to leave tracks alongside the San, with the hope of heading together towards a sustainable future.

About the author

Aleksandra Ørbeck-Nilssen is a 26-year-old viking from Norway. She is the founder and CEO of Nanofasa Conservation Trust, and has a heart that is dedicated to Namibian communities and wildlife conservation.

Aleksandra Ørbeck-Nilssen is a 26-year-old viking from Norway. She is the founder and CEO of Nanofasa Conservation Trust, and has a heart that is dedicated to Namibian communities and wildlife conservation.

After working many years as a model and actress at an international level in Paris and New York, Aleksandra chose to settle in Africa. She now works to protect the remaining wilderness in Namibia – the home of giant trees, endangered wildlife, and the ancient San tribe.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()