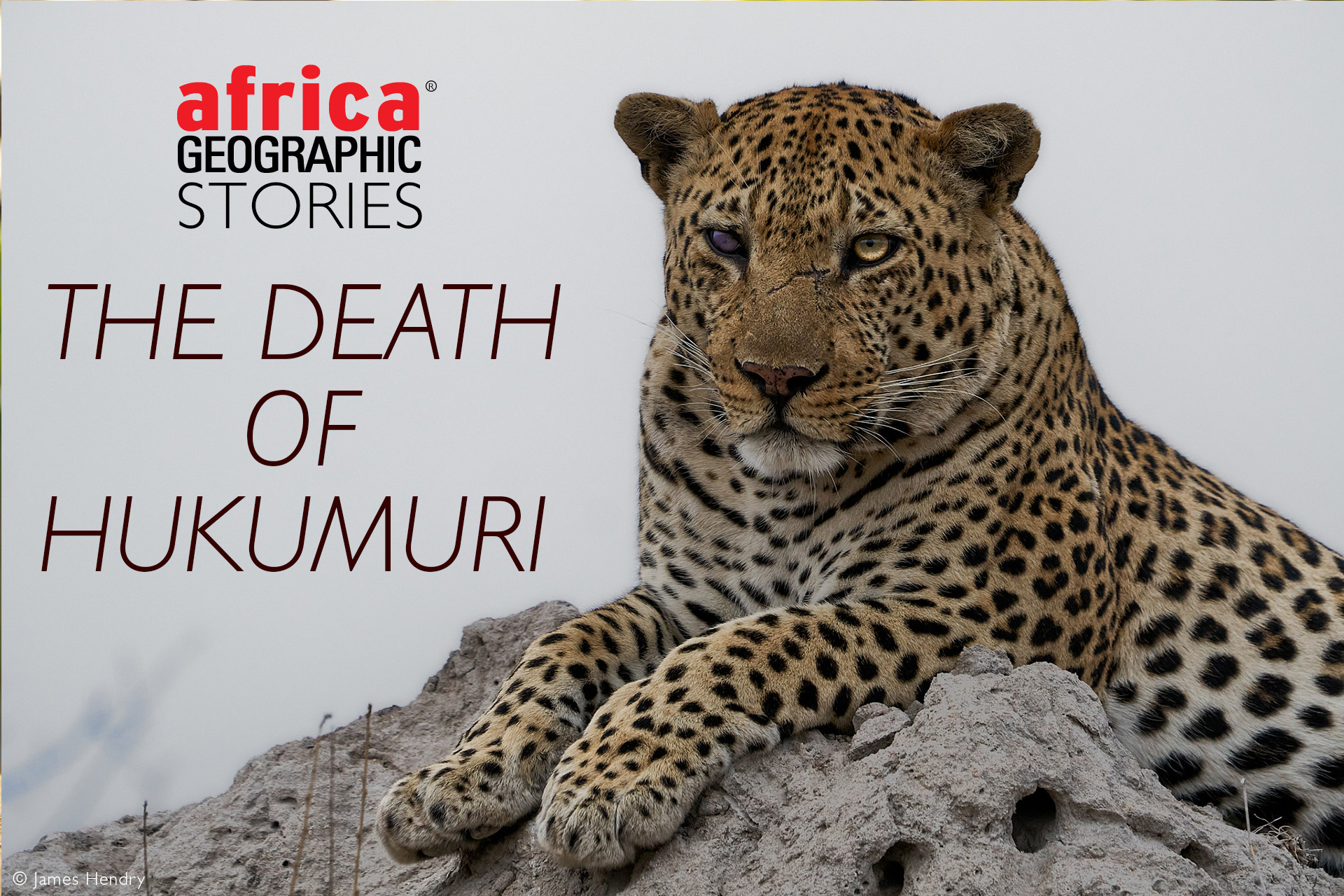

Hukumuri, a famous Lowveld leopard, is dead. He died on 16 January 2021 – shot by the local authorities in a rural village after he killed livestock and a dog. These are indisputable facts, and an ongoing investigation may reveal more detail. Huk, as some know him, was a favourite amongst tourists to the northern Sabi Sands Game Reserve and amongst online live safari followers. He was not in the Sabi Sand Game Reserve at the time of his death, and the game reserve management had no hand in his death.

We have, as far as possible, in the short time available, tried to establish exactly what the facts surrounding Hukumuri’s death are. We have spoken to park officials, and yesterday Jamie visited Mr Nabot Mathonsi, the village headman, and the homestead of Romina Mathonsi who lost valuable livestock – almost her entire life’s savings. Here then are our findings, followed by our personal thoughts about a leopard we knew and loved.

This, then, is what we know with relative certainty:

- The Mpumalanga Parks and Tourism Authority (MPTA) has confirmed to Africa Geographic that Hukumuri was shot by staff of the Manyeleti Game Reserve with the full authority of the MPTA. Most importantly, this was a ‘last resort’ decision. The staff of the Manyeleti made multiple attempts to catch the leopard under challenging circumstances. If further details become available, we will share them.

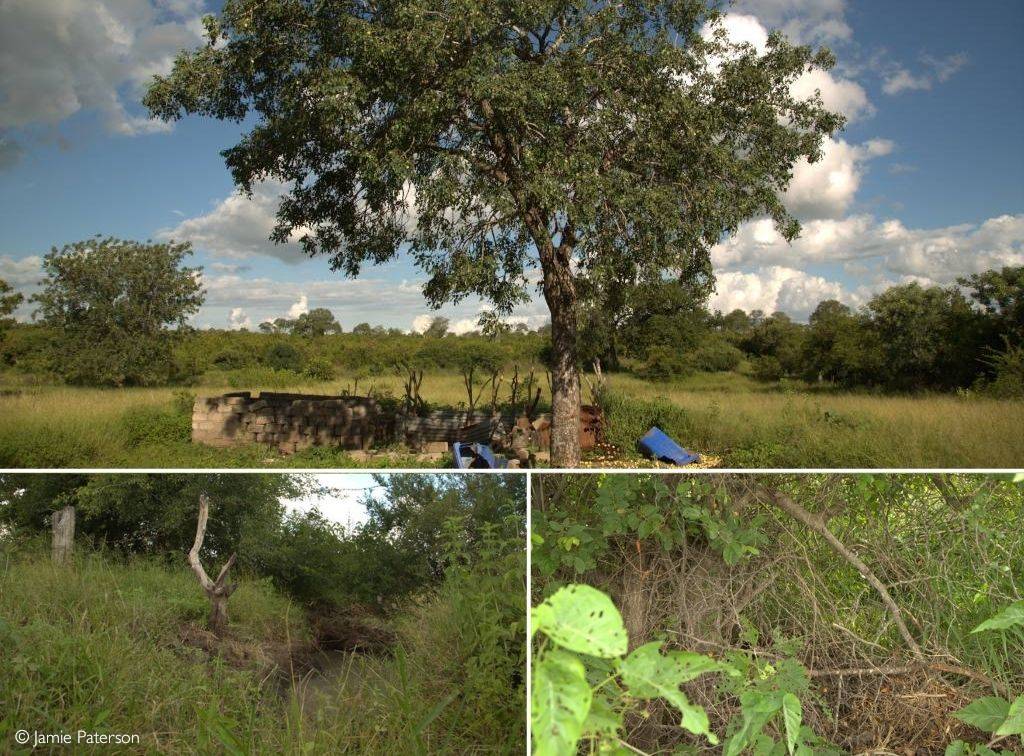

- He was shot in a village a few kilometres north of the Sabi Sands Game Reserve, some 200 metres west of the Manyeleti fenceline.

- Hukumuri killed several goats, pigs and at least one dog, causing a potentially devastating loss for more than one family.

- Ms Mathonsi, who has seven children, including young toddlers and lives in abject poverty, lost all of her female livestock and one of her dogs when it tried to chase Hukumuri from her home. The animals had been placed in a ‘kraal’ for the night, and she cried when relating the story to us. When the leopard was tracked down, he was lying beneath a buffalo thorn just 100 metres from her homestead.

- Despite the obvious frustration they felt, the community did not take matters into their own hands but called the relevant conservation authorities.

- Many of the people living around the game reserves in the area are resentful about the lack of benefit (employment) and the perceived lack of help with compensation when livestock is lost to wild predators. The process of applying for compensation requires a certain level of literacy from the applicants, yet few of the villagers have had any formal education.

- The potential for conflict in the area where Hukumuri died is very high. There is no buffer zone between the fence and the villages – there is no soft boundary, and people live virtually up against the fence.

- We know, as a hugely experienced guiding friend reminded me, that Hukumuri had become a potential danger to human life. It is often small children who look after livestock in the villages and a non-territorial, possibly injured or sick leopard is not only a threat to livestock but also villagers – especially young children herding livestock. Both Mr and Ms Mathonsi told us that they were terrified for the lives of the village children.

- We know that Hukumuri was being pressurised by other males in his area and had probably lost his territory – maybe even more than once. This comes from guides who work in the area and have spent extensive periods with him.

- We know that darting and then relocating leopards back to reserves they have left, because they’ve been excluded from territories, seldom works. The costs of relocation are also very high. Despite this, the Manyeleti did make multiple attempts to catch Hukumuri.

- Sadly, we also know that this will not be the last time something like this happens despite many people’s best efforts.

When a leopard such as Hukumuri dies, many of us who knew him, feel devastated. It feels like we have lost a close friend, or even, dare we say it, a beloved pet. Hukumuri, of course, would not have mourned our passing because he did not seek out the company of the countless humans he met in the way that a pet might have. But that doesn’t make it any easier for those of us who mourn the loss of a favourite leopard.

We knew Hukumuri for many years – we watched him forge his first territory – full of youthful exuberance and powerful, uncompromising energy. We watched him hunt warthogs to the delight of a live, international, television audience. We noted with trepidation the conflict that left him blinded in one eye – we wondered if he’d manage to hold onto his territory. He became a figure of admiration as he overcame this disability, and then we delighted when he fathered cubs. Sadly, we also noted that despite his relative youth, he seemed to be feeling the pressure from several other male leopards in his area, and his future became uncertain.

It is this sort of rollercoaster drama that makes the lives of animals like Hukumuri so compelling. There will be those who argue we should watch in a detached ‘scientific’ manner. Then again, there are plenty of scientists who have shed tears at the loss of a favourite animal.

When the death of a beloved animal like Hukumuri comes brutally, the pain is that much worse. (We must remember that, in the wild, death very seldom comes peacefully). When the death is brutal and at human hands, the pain we feel often spills over to rage. Anger and pain create mists through which it is very difficult to evaluate situations objectively.

None of this will help the feeling of loss that many of us feel – be it a sense of loss because we knew him, or because we simply love these mystical, spotted cats and can’t bear the thought of them being destroyed in a time of such wanton environmental carnage. But these are the realities of conservation in Africa.

Human-wildlife conflict is one of, if not the greatest challenge facing African nature conservation. There are some very complicated situations at play where people and parks meet. In a simplistic nutshell, the people living on the borders of conservation areas are usually impoverished. They have often been removed from the land or excluded from benefiting directly from it. This has created a situation where conflict with wildlife and wildlife authorities is all but inevitable. If disputes are not quickly and timeously resolved, poor people who bear the brunt of the conflict with wildlife, take matters into their own hands.

In this case, the villagers concerned, while frustrated, further impoverished and also fearful, did not do so and they are to be commended for their patience. Remember that this is a village where the unemployment rate probably exceeds 70 percent. Those who do have jobs are frequently employed in ecotourism. The positive attitude that many community members show to conservation and game reserves is partly a function of this employment.

The loss of Hukumuri is a tragedy; there are no two ways about it. He was only around nine-years-old when he died. In a perfect world, he would have sired more cubs, established himself in another area and continued to delight us with his one-eyed belligerence. But this is nowhere close to a perfect world, and because of the realities of nature conservation in Africa, we have lost a leopard – to many almost a friend.

However, we do not believe that the sadness of this tragedy should overshadow the realities of the situation or override an objective perspective. Hukumuri was pressurised in his territory; he left the protection of the reserve; he killed livestock and posed a genuine threat to human life; the Manyeleti staff did what they could to mitigate the situation; they took the last-resort decision to destroy Hukumuri because they did not see another option.

Were mistakes made? Possibly – we’re all human. Will this happen again? Almost certainly. We must work tirelessly to inform ourselves – to understand the wildlife, the people who live beside it and the myriad factors at play in the complex arena that is African nature conservation. We need to learn to treat the people most affected by conflict with wildlife with the same compassion we would show the animals concerned. Only then can we hope to avoid further tragedies like this one.

Rest in peace Hukumuri. ![]()

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()