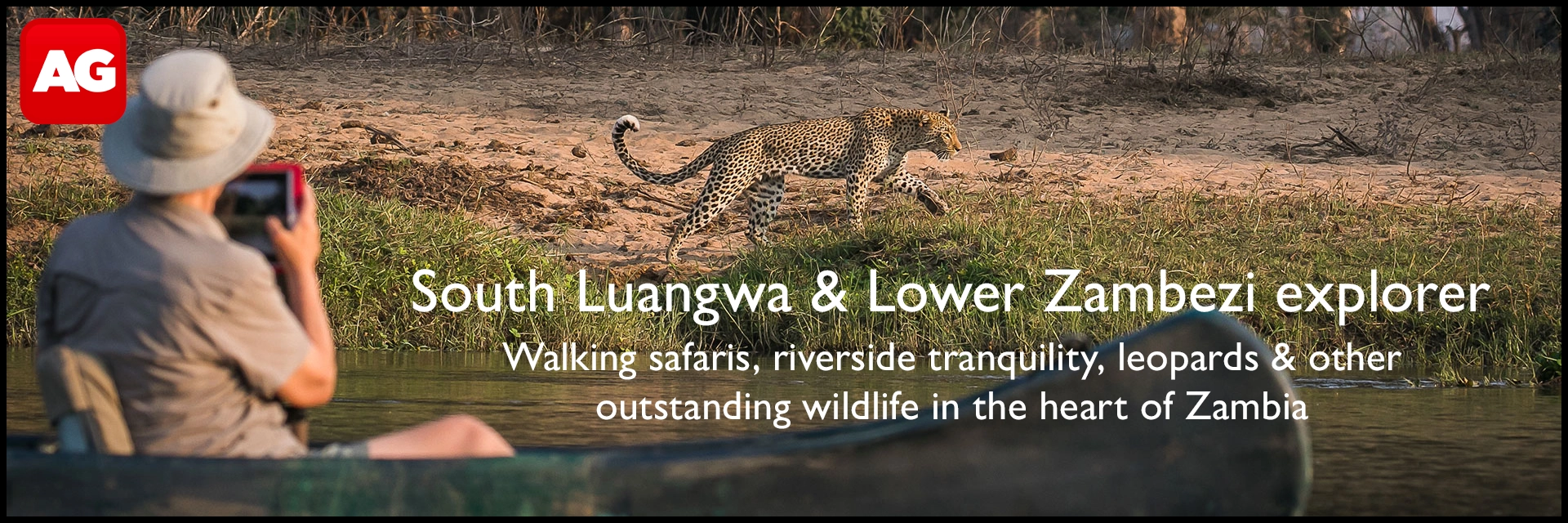

A TIME OF CHANGE FOR SELOUS

This is a time of change for Tanzania’s Selous Game Reserve – some good, some terrible.

At the Mtemere gate of Selous lies an ancient husk of an old steam train, the joints and bolts hidden beneath over a century’s worth of rust and grime. Shining against the aged relic, the attached plaque reads “This steam engine was left behind in 1917 by the German troops under Lettow-Vorbeck near Madaba/Selous Game Reserve”.

Time has taken its toll on the old train, and yet, beyond the gate, the vast wilderness landscape lies almost unchanged – for now. In common with so many of Africa’s wild places, the Selous Game Reserve has always engendered a feeling of time standing still – its vital life forces untouched by the passage of the years. Yet nothing seems to escape the inexorable march of time or the mark of human progress forever…

The Selous Game Reserve becomes Nyerere National Park

The entire protected area, historically known as the Selous Game Reserve, and for now recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, is 54,600km2 (5,5 million hectares) and is one of Africa’s largest and oldest protected areas. It was named after Frederick Courteney Selous, a British explorer, officer, hunter, and conservationist, who was killed by a German sniper during World War I near the Beho Beho River in the western section of the reserve, where his remains are buried today.

The Beho Beho and Ruaha rivers are just two of the many tributaries of the mighty Rufiji River, the largest river in Tanzania, which fans out into an intricate network of channels, lakes and swamps across the riverine regions of Selous. During the wet season, the Rufiji becomes a swirling torrent of brown water before spreading across floodplains downstream, filling the swamps, clearing sediment build-up, and refreshing the oxbow lakes, effectively changing the face of the landscape every year. The crocodile-infested river divides the Selous Game Reserve into two and, up until very recently, the northern sector of Selous (around 8% of the total area) was set aside for photo tourism purposes. In contrast, the rest was divided into hunting “blocks” of around 1,000km2 each.

In 2019, President John Magufuli announced that the Selous Game Reserve would be split in two. The larger portion (30,893km2 – more than twice the size of the Serengeti National Park) becoming the Nyerere National Park, while the southern section will, presumably, remain the Selous Game Reserve. While the exact boundaries of this new national park have yet to be formally announced, it will be the largest national park in East Africa and is named after independent Tanzania’s first president, Julius Nyerere – an iconic figure in Tanzania’s history.

What does this mean?

National Parks are afforded the highest levels of legal control over human activity and habitation within the park and are managed by the Tanzanian National Parks Authority, TANAPA. Game Reserves are similarly protected but are managed by the Tanzania Department of Wildlife with regions set aside for trophy hunting.

President Magufuli has made clear that the intention is to increase the tourism revenue potential of the area. While the largest protected area by far, Selous Game Reserve has typically been overshadowed by the northern Tanzanian safari circuit, including Serengeti National Park, at least in terms of photo tourism. In reference to the hunting blocks of the old Selous Game Reserve and the creation of Nyerere National Park, President Magufuli stated that “tourists come here and kill our lions, but we don’t benefit a lot from these wildlife hunting activities”. Apparently, the park management intends to improve road network to be accessible for the majority of the year (most of the luxury camps in the reserve typically close from April to June at the height of the rainy season), and the government has called on investors to look into creating new camps.

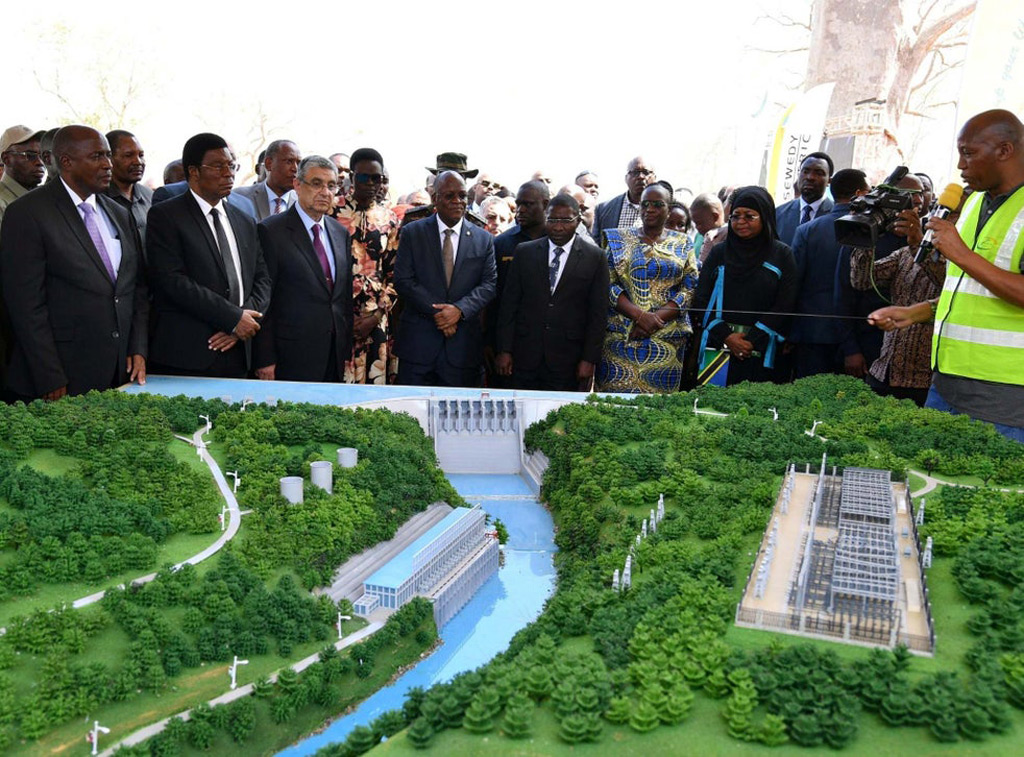

Yet for all the protection afforded by “national park” status, the plan is for the newly formed Nyerere National Park to include one of the largest dams and hydroelectric power stations in Africa. This dam will forever change the natural ebb and flow cycles of the Rufiji River and its tributaries, oxbow lakes and swamps.

Progress be dam(n)ed

Along its journey through the Selous to the Indian ocean, the Rufiji River passes through Stiegler’s Gorge, once considered to be one of the main attractions in Selous, where the water plunges through a narrow ravine with walls 100 metres high. Stiegler was a German engineer who set out to measure and survey the gorge in the early 20th century, where he met an unfortunate end after being charged by an elephant and falling off the edge of the ravine. While the gorge’s potential for infrastructure was recognized even then, both for hydropower and irrigation, various obstacles continued to preclude its development. When President Nyerere turned the newly independent country’s plans towards hydropower, donors chose to finance smaller hydropower dams at Kidatu, Mtera and Pangani.

After a series of extensive studies and investigations, the World Bank concluded that the construction of a large dam was simply not viable at Stiegler’s Gorge. Plans continued to fall through until current President Magufuli announced in 2017 that the dam would be a flagship development project of his government. Logging teams moved into the area at the beginning of 2019 and, as of June 2020, the project was declared to be close to 40% complete (though this seems highly unlikely for a construction project of this magnitude). According to a statement by the President Magufuli, only 10% of the Tanzanian population is connected to the national power grid, and the dam is expected to contribute some 2,115 megawatts in a country where regular load shedding causes enormous losses to the GDP.

While there is no question that Tanzania needs to increase its electricity production substantially, critics of the Stiegler’s Gorge dam project are far from convinced that a mega-dam is the answer. There are profound concerns surrounding the economic and technical viability of the project (a full and objective assessment of the costs can be found here), and many external experts suggest that alternative options such as smaller dams, natural gas or renewable energy sources such as wind and solar would have been less risky. Yet it is a risk the government of Tanzania appears to be determined to take, regardless of the consequences, be they financial or, perhaps even more concerning, ecological.

EIA? What EIA?

The controversial dam and Julius Nyerere Hydropower Station, to be built by Egyptian construction companies, are expected to cover around 1,350 km2 (135,000 hectares) upon completion. This covered area equates to about 2,5% of the total protected area of the Selous but will destroy significant portions of forest and riverine habitat and impact the downstream ecosystems. The plans were met with resounding criticism from many conservation organizations, as well as the IUCN and UNESCO’s World Heritage Centre. They called for an immediate halt to logging and construction efforts.

The Environmental Impact Assessment submitted in 2018 by the University Consultancy Bureau of the University of Dar es Salaam has been slammed by critics (including this technical review by the IUCN) for a combination of factual errors, an oversimplified approach to an immensely complex project, and the omission of several significant environmental consequences. The EIA does not meet the required international standards on almost every level and goes so far as to suggest that the construction of the dam will result in increased biodiversity in the area and control salinity levels downstream. Dr Rolf Baldus, an economist and expert on the Selous, concluded that this “EIA does not deserve the name it carries, and its academic authors have lost all scientific credibility”.

The price of power

Before the 2018 EIA, the WWF released their assessment of the Stiegler’s Gorge Hydropower Dam, entitled “The True Cost of Power“. The report provides a far more substantive evaluation of the impact of the proposed dam, from disrupted connectivity of habitats and erosion to increased downstream sedimentation and the loss of downstream lakes. It also highlights the fact that the area downstream of the gorge is the richest habitat area in the Selous, with the largest concentration of fauna and flora. This area is almost entirely dependent on the seasonal pulse of the river. Even further downstream, though equally reliant on the seasonal flow of the river, the Rufiji River Delta is home to the largest mangrove stand in East Africa and is a designated RAMSAR site. The livelihoods of the populations reliant on the river for agriculture and small fishers are also of concern. The report concludes that “it is unprecedented to risk losing the integrity of not one, but two globally significant protected areas to a hydropower project”.

President Magufuli has dismissed environmental concerns. “Tanzania is among global leaders in conservation activities, having allocated over 32% of our country’s total land to conservation,” he said. “Nobody can teach us about conservation.”

A World Heritage Site in Danger

Somewhat unsurprisingly, the World Heritage Committee is expected to strip the Selous Game Reserve of its World Heritage status should these plans continue due to the significant and irreversible damage to the region’s Outstanding Universal Value. The Committee had already placed the Selous on the List of World Heritage in Danger in 2014. According to their report at the time, the number of elephants and rhinos in the reserve has dropped by almost 90% since 1982. While these numbers have stabilized in the last few years due to concerted conservation efforts, there are believed to be just over 15,000 elephants and a handful of black rhino remaining. To put this into perspective, there were over 100,000 elephants in the Selous Game Reserve in 1976.

To add insult to ecological injury, a uranium mine was established in the south-western corner of the Selous in the 1990s which required an extensive boundary modification to the World Heritage Site. By January 2017, there were 48 prospective mining concessions within the greater Selous ecosystem. While the Tanzanian Wildlife Authority has confirmed that none of these will be opened for exploration and no concession will be granted in the future, a 2018 Geological Survey of Tanzania confirmed the presence of copper, silver, cobalt, zinc, and gold in the Selous.

Conclusion

In general, internal criticisms of the Stiegler’s Dam project have been somewhat muted, which is perhaps unsurprising after Tanzania’s environment minister announced that “the government will go ahead with the implementation of the project whether you like it or not…those who are resisting the project will be jailed”. According to international experts, the chances are that the construction of Stiegler’s Gorge Dam will cost far more than anticipated and its completion will be delayed, probably by more than six years. In the process, conservationists estimate that close to 3 million trees will be cleared in the dam’s intended reservoir.

For now, however, life goes on in Nyerere National Park and Selous Game Reserve as it has for thousands of years, albeit largely at the mercy of human impact. Elephants wade through the swamps, dwarfed by enormous, towering borasis palms, and the park’s network of waterways continue to supply the vast abundance of life around them.![]()

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()