ELEPHANT IDENTIFICATION

To the novice eye, most wild animals of the same species look mostly identical to each other unless marred by a prominent scar or perhaps sporting a different colour variation. However, closer observation reveals that each individual, whether leopard, lion, or elephant, possesses a set of identifying characteristics as unique as human fingerprints. For researchers monitoring these animals, being able to identify individuals is extremely useful for estimating populations and understanding demographics. However, the process is often time-consuming, labour intensive and subject to human bias. For 25 years, the team at Elephants Alive, spearheaded and led by Dr Michelle Henley (last author), have developed their own solution for elephant identification: a System of Elephant Ear-pattern Knowledge (SEEK).

Despite their size, monitoring elephants to estimate populations and demographics comes with its own set of complications. Traditional capture-mark-recapture techniques are expensive, dangerous, and impractical, large-scale aerial surveys are prohibitively expensive, and dung counts vary depending on vegetation type. This has necessitated the use of alternative techniques such as mark-resighting studies which in turn generally rely on photo-identification. The use of photographic records depends mostly on manual matching techniques and human memory, and while automated software models are in use, they still require further development.

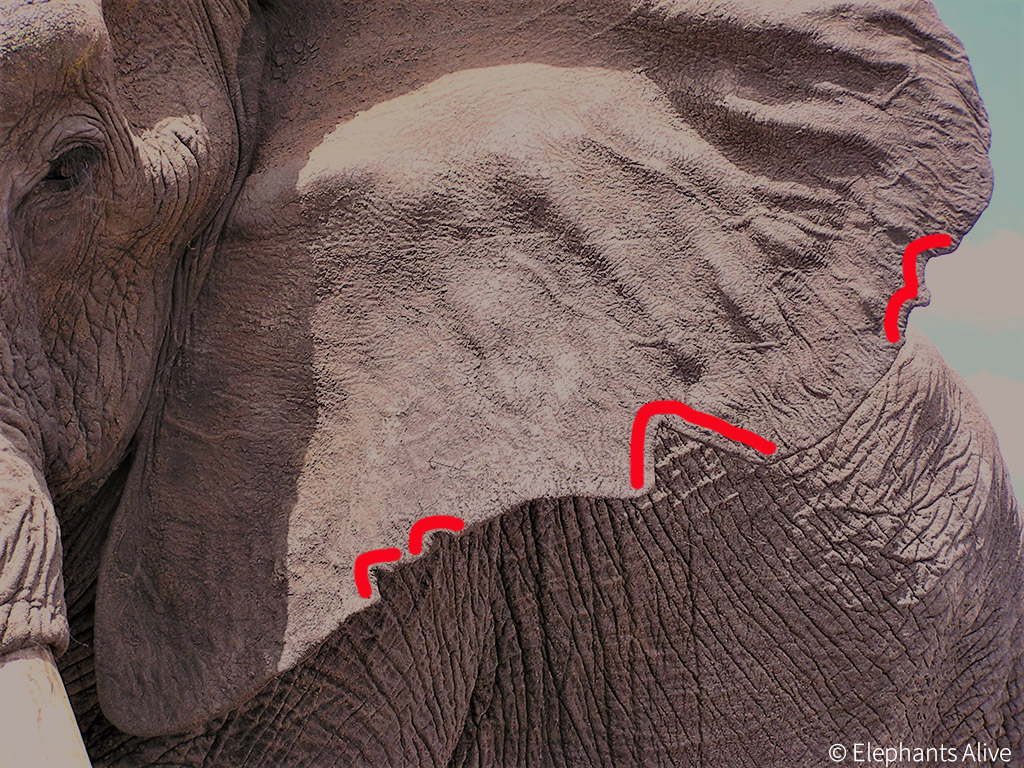

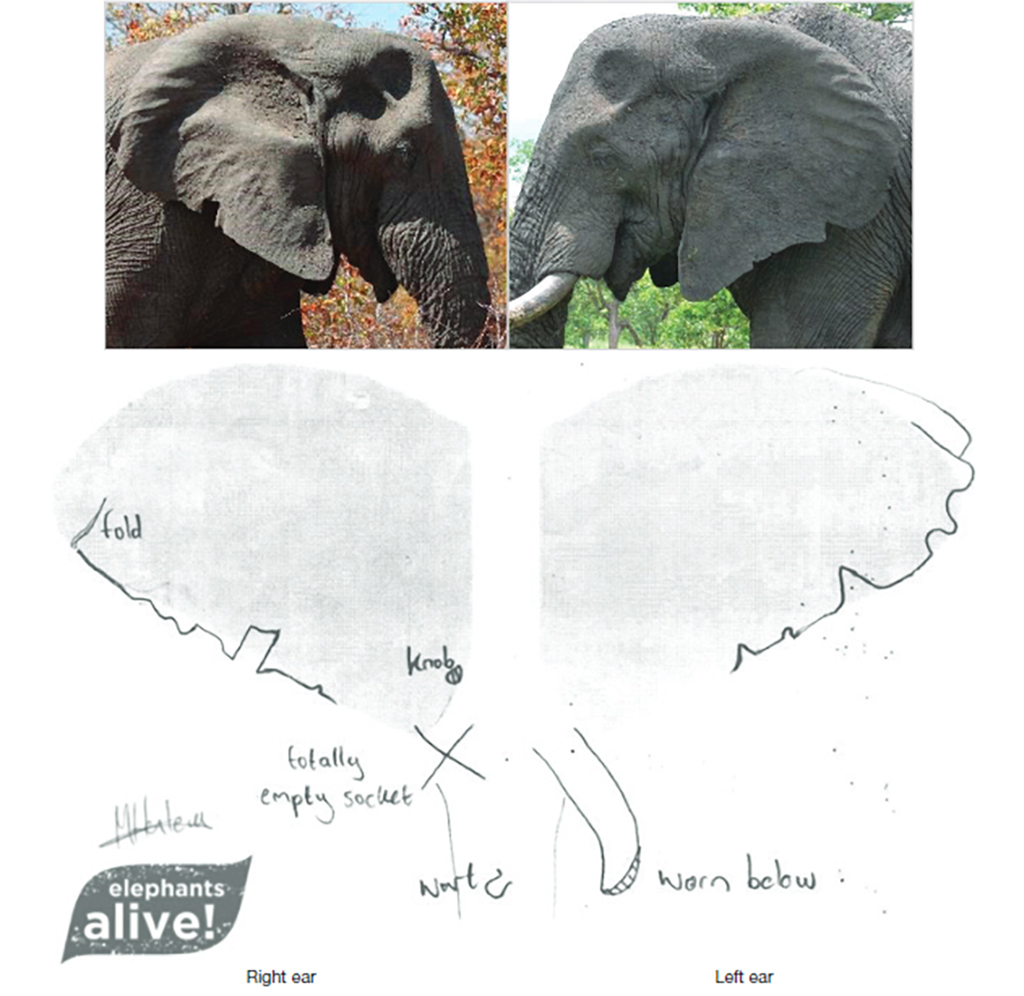

The Elephants Alive team monitor elephants across the Associated Private Nature Reserves (APNR) on the western boundary of the Kruger National Park and have been conducting field research since 1996. The team began putting together their own simplified coding system at the start of the period which initially entailed creating detailed drawings of the ear features of individual elephants. The study was officially registered with South African National Parks (SANParks) in 2003 and has continued until the present day.

In 2012, the first comprehensive coding system was developed. The animal was grouped first according to sex and age and then incorporated into a feature and element system. The method was refined over time, to simplify the system and exclude observer bias for more complex shapes.

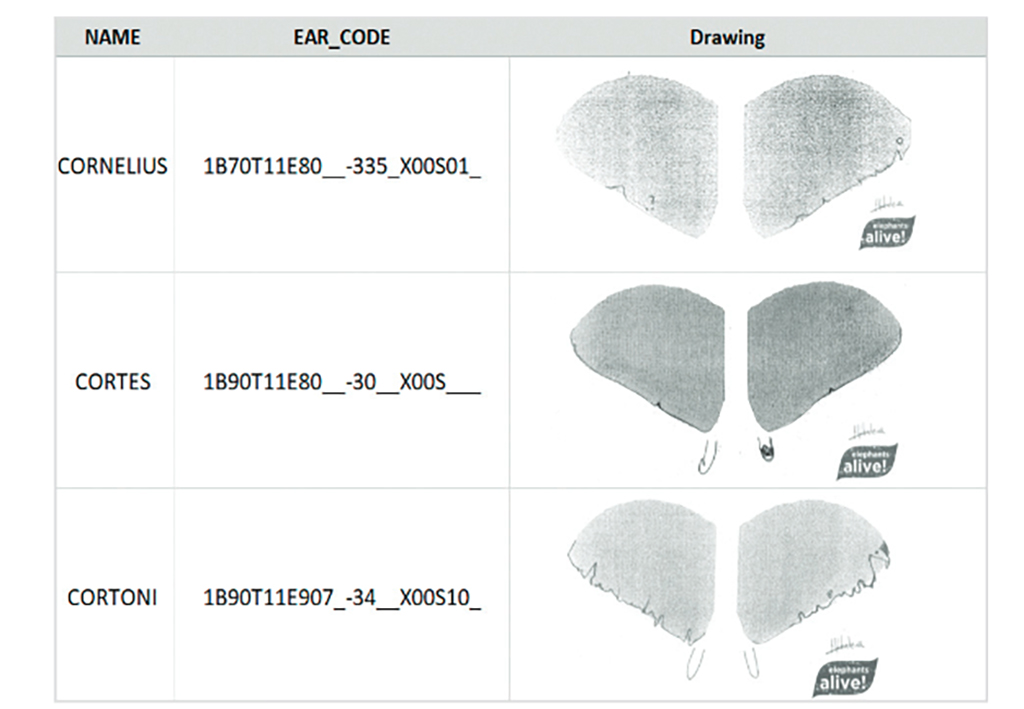

Today, each elephant assigned to the database has been given a unique code that corresponds to specific aspects of that individual. The first letter of the code will be either B (bull) or C (cow) and the following two numbers place the individual in an age bracket. Following that, the presence or absence of tusks is recorded. From there, features on the left ear have been assigned numbers depending on the position on the ear itself – with the most prominent tear listed first, followed by the most prominent hole, the second most prominent tear and the second most prominent hole (in this exact order). The right ear follows the same pattern. The coding system is completed with reference to the existence of extreme features (applied to ear tears or holes that cover more than 25% of the ear) and any other special features (a missing tail for example).

So, for example, B70T01E808_-403_X00S00 is a bull elephant, born between 1970 and 1979 (B70), with a tusk on his left side but not the right (T01). The most prominent tear and the second most prominent tear are both at the 8 position of his left ear (E808). On his right ear, the most prominent tear is on the 4 position, while the second most prominent tear sits on the 3 position (-403). Neither ear has any prominent holes. He does not have any extreme features nor any special elements (X00S00).

SEEK has been developed to follow the rules of the search function of both Microsoft Excel and Microsoft Word, allowing researchers to rapidly narrow down their search when presented with an image of an elephant they are trying to identify. If all recorded individuals are ruled out, the new elephant is added to the system. The additional Microsoft Office Wildcard function also allows for situations where not all characteristics are observable (if presented with only one side of the individual, for example).

The extensive development of SEEK is a truly extraordinary accomplishment, born of decades worth of research and practical experience. The evolution of this method has been shaped by the pragmatic realities of fieldwork while still allowing for identification accuracy, resulting in a system that can be applied by other such research programmes as well as an extensive historical database of elephant individuals in the Greater Kruger. From behavioural studies to understanding long-term population trends, individual identification is vital in the efforts to conserve one of the most iconic animals in Africa.![]()

The full paper can be accessed here: “System for Elephant Ear-pattern Knowledge (SEEK) to identify individual African elephants”, Bedetti, A., et al (2020), Pachyderm

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()