While there is a tendency to view the bushmeat trade as a homogenous process with the animals as the generic resource, researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology and the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research propose a different approach. They suggest that understanding the drivers of hunting and trading in bushmeat is essential in developing a multifaceted strategy in managing and mitigating the effects on species numbers, especially in areas where consuming bushmeat is a vital aspect of everyday life.

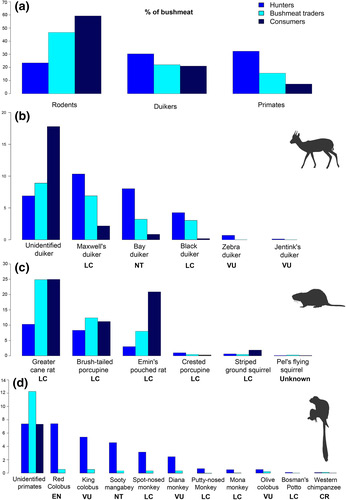

While unsustainable hunting of certain species has had a devastating effect on species throughout the world (and continues to do so), viewing all bushmeat trade through one lens has the potential to over-simplify the complexity of the situation. For example, different approaches are needed for rodents as opposed to primates, since rodents have high reproductive rates and their populations are more resilient when hunted, whereas primate populations are less resilient, and their consumption is associated with increased risks of disease. Researchers set out to understand why certain species are selected by conducting interviews with the people around Taï National Park in Côte d’Ivoire.

Because bushmeat trade is largely illegal, the researchers were initially met with a certain hesitance to provide information but, through careful work with local informants, they were able to interview 348 hunters, 202 bushmeat traders and 985 bushmeat consumers.

They identified several different motivating factors for each member of the trade chain from hunters to consumers and traders: financial gain, nutritional necessity, and cultural reasons. There are over 500 bushmeat species in Sub-Saharan Africa alone, and according to previous research, around 80% of bushmeat in West and Central Africa comes from fast-reproducing generalists such as rodents and small antelopes. These species can be a vital component of food security and livelihoods in certain areas. Interestingly, the research indicated that where hunters or consumers were aware that unsustainable hunting would have negative ecological effects on primates, they responded positively by avoiding hunting or consuming primates. Bushmeat traders, on the other hand, showed no such change in behaviour.

In situations where access to alternative protein sources was restricted, hunters and consumers generally targeted rodents. In contrast, hunters looking to make money from trading in bushmeat either targeted duiker or primates, and primates (7% of the analyzed trade) were almost invariably consumed as a “luxury” meat. Thus, the researchers point out, addressing a shortage of proteins through development-related projects could mitigate one of the main drivers of bushmeat trade but, at the same time, increased economic development could see an increase in primate hunting to feed a growing market for meat seen as a luxury. So, this approach would need to be complemented by educational strategies. Poorly planned interventions could have disparate and even unintended consequences at different stages of the bushmeat trade, as well as for the multiple species affected by it.

The study suggests that while the development, educational and cultural strategies currently broadly applied to control bushmeat consumption have the potential to be effective, they need to be directed at the correct groups of people in the correct manner to avoid wasting scant resources. While there is an understandably urgent need to protect certain species from unsustainable hunting, policies need to be tailored for each specific species. The authors emphasize that there is no “one-size-fits-all” solution to bushmeat consumption and strategies that aim to have conservation benefits need to be based on research that provides a clear understanding of the process within each community.

The study suggests that while the development, educational and cultural strategies currently broadly applied to control bushmeat consumption have the potential to be effective, they need to be directed at the correct groups of people in the correct manner to avoid wasting scant resources. While there is an understandably urgent need to protect certain species from unsustainable hunting, policies need to be tailored for each specific species. The authors emphasize that there is no “one-size-fits-all” solution to bushmeat consumption and strategies that aim to have conservation benefits need to be based on research that provides a clear understanding of the process within each community.

As Hjalmar Kühl, one of the leaders of the research team explains: “If we really want to solve the problem of the overexploitation of wildlife and reduce the threats associated with it, for species conservation and human well-being, we need to tackle it at its roots. We cannot continue ignoring this problem, but we need to invest resources and develop strategies that really help to create a more sustainable human-wildlife co-existence.”![]()

The full study can be accessed here: “Saving rodents, losing primates – Why we need tailored bushmeat management strategies”, Backmann, M., et al (2020), British Ecological Society

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()