The fastest land mammal races against extinction

The cheetah is one of the oldest of the big cat species, with ancestors that can be traced back more than five million years to the Miocene era. They are also one of the most endangered species on the planet. One hundred years ago there were 100,000. Today there are fewer than 10,000.

The cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus) is famous for its speed, reaching over 100 kilometres per hour in short bursts. All parts of its body have evolved for precision and agility, from the small aerodynamic head, lean body and long legs to a tail that works like a boat’s rudder.

People often confuse cheetahs with leopards or jaguars, but several points of physical difference make it easy to distinguish them. In addition to having a light-boned, elongated frame, the cheetah’s undercoat is marked with solid black spots instead of rosettes. Cheetahs also possess distinctive ‘tear marks’ that extend from the corners of their eyes along their nose to their jaw. The biological purpose of these marks is to cut the sun’s glare so that they can see more clearly across long distances.

History of the cheetah

The cheetah was once one of the most widely distributed land animals. Phylogenetic research has shown that the cheetah evolved from a common ancestor with the puma and jaguarundi in the Americas during the Miocene era, which was five to eight million years ago. Over time, the cheetah migrated, crossing land bridges from North America into China, through India and Europe, before finally settling in Africa as recently as 20,000 years ago.

Genetic research indicates that today’s cheetahs are descendants of but a few animals that survived 12,000 years ago following the last glacial event in the Pleistocene era. The population then experienced what is referred to as a ‘population bottleneck’, a sharp reduction in size. As a result, cheetahs lack genetic diversity, making them more susceptible to certain feline diseases.

The earliest record of human interaction with cheetahs dates back to the Sumerians in 3,000 BC. In Egyptian history, it was believed that the cheetah would swiftly carry away the Pharaoh’s spirit to the afterlife, and symbols of cheetahs have been found on many statues and paintings in tombs. They have also been long revered as hunting companions for royals.

Modern decline

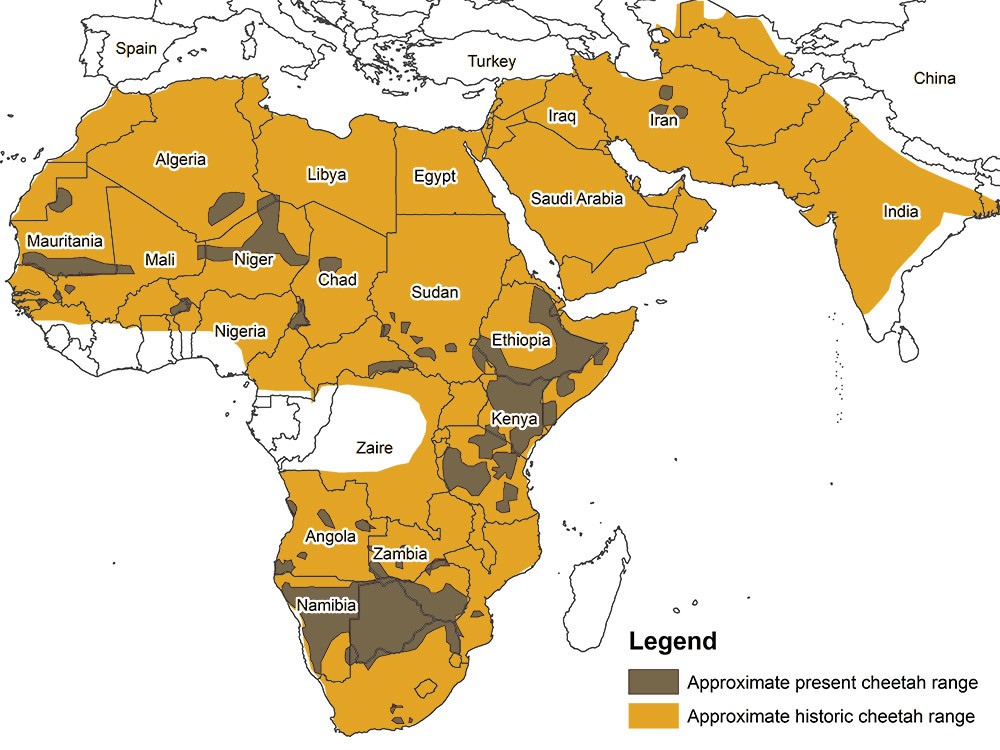

At the beginning of the 20th century, approximately 100,000 cheetahs were found in at least 44 African countries. Today, fewer than 10,000 cheetahs are left on the continent, and they are found in small, fragmented areas spread across only 23 countries, at the most. This represents a decline of 90 percent in the last 100 years.

Although seven subspecies were originally proposed based on morphological criteria, five are currently recognised. The Southern African cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus jubatus) is the largest remaining population and was originally found throughout Southern Africa, but now is mostly limited to Namibia, Botswana and South Africa. The East African cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus raineyii) has the second-largest wild population in Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda and Somalia. The Central African or Sudan cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus soemmeringii) is found in Sudan, Cameroon, Niger, Nigeria, Chad, Ethiopia and the Central African Republic. Approximately 250 North African or Saharan cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus heck) are now found mainly in the central western region of the Saharan desert and the Saheland. And less than 100 Asiatic cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus venaticus) remain in Iran despite being previously spread across Asia.

The king cheetah was once thought to be a separate subspecies (acinonyx rex), but is actually a mutation due to the same recessive gene responsible for the two types of coats in domestic tabby cats – the striped mackerel tabby and the swirl-patterned classic tabby. King cheetahs are easily recognisable thanks to their coats, which have large, solid spots, some of which have merged to form dark stripes down the middle of their backs. King cheetahs also have somewhat of a larger build than the average-sized cheetah. Rarely seen in the wild, they are more frequently found in captivity, where they are intentionally bred.

Threats to survival

For many African wildlife species, living within a protected national park or private game reserve, such as the Maasai Mara Game Reserve in Kenya, the Serengeti National Park in Tanzania, or the Kruger National Park in South Africa, is the difference between life and death. However, for species like the cheetah, living in protected areas results in greater competition with other larger and more aggressive predators that steal their kills and kill their cubs. Consequently, 90 percent of all cheetahs live outside of protected parks and reserves, making them more vulnerable to human conflict.

Most people who live alongside cheetahs are rural communal farmers whose livelihoods depend on the health and well-being of their livestock. Most are poor and cannot afford to lose even a small fraction of their animals to predators. These farmers have traditionally viewed cheetahs as vermin, a nuisance and a threat. Some governments sanction herd protection programmes allowing cheetahs on farmlands to be trapped, removed, or killed on sight. Popular during the 1970s and 1980s, these programmes led to a rapid, widespread reduction in the number of wild cheetahs. Still, fortunately, since then, the introduction of non-lethal predator control techniques has stemmed the tide.

Bush encroachment is a form of desertification caused by the overgrazing of arid landscapes, which results in the prolific growth of native plant species commonly known as thornbush. On traditionally open savannas where cheetahs hunt, bush encroachment alters the landscape and limits the cheetah’s success in hunting, creating an imbalance in the mix of wildlife.

Bush encroachment is devastating for cheetahs as their habitat is now nearly impenetrable. As the cheetah sprints through thornbush, its eyes are scratched, often resulting in permanent damage. The cheetah relies on its eyesight to hunt and detect threats, but with impaired eyesight, cheetahs are more likely to consider livestock prey, becoming a problem animal for farmers, and thus increasing conflict.

Another issue impacting the cheetah is tourism. Everyone who travels to Africa and goes on safari wants to see a cheetah. While tourism helps to bring the species’ international attention and instils economic value in the species’ survival, crowds of multiple vehicles surrounding cheetahs are dangerous for the animal. The disruption of a mating event or a hunt, or getting too close to a mother with offspring, can have a lasting and devastating effect.

Exotic pet trade

Most disconcerting of all, an estimated 300 cheetah cubs are being smuggled out of the continent each year, mostly to the Gulf States – to supply the illegal pet trade. Cheetahs as exotic pets are considered status symbols and live inside private homes, sleeping on furniture or tile floors that bear little resemblance to their natural habitat. Photos on social media depict cheetahs with gem-studded collars riding in speedboats, sitting in luxury vehicles and posing at social functions.

Keeping a wild cheetah as an exotic pet undermines the species. Five out of six poached cubs are believed to die before reaching their final destination, while mother cheetahs are often killed defending their cubs. Cheetah cubs that survive long enough to be sold most likely do not make it beyond two years of age.

Those that do, often become sick or disabled and die from improper care.

Strategies for survival

Although people are the root of most problems facing the cheetah, they are also the solution. Over the past 12 years, conservation professionals have come together to devise strategies to help the cheetah win its race for survival.

In 1994, the Cheetah Conservation Fund (CCF), a research education and conservation institution based in Namibia, initiated a programme to provide rural farmers with livestock guarding dogs as a non-lethal means for predator control. Two rare, large breeds were chosen, the Kangal and the Anatolian shepherd, because of their loud bark, protective nature and successful history guarding livestock in Turkey – a country with similar climate and terrain.

CCF livestock guarding dogs are credited with saving the lives of hundreds of cheetahs each year. Farmers with a CCF dog report a drop in stock losses due to predation anywhere from 80 to 100 percent, meaning they no longer feel as much pressure to trap or shoot cheetahs. CCF has placed more than 650 of these specially trained dogs and helped launch sister programmes in Botswana, South Africa and Tanzania.

In 2001, CCF also launched a project to combat bush encroachment by transforming selectively harvested, excess thornbush into a biomass fuel product. Today, the manufacture of BUSHBLOK™, a clean-burning, low-emission fuel log, helps restore thousands of acres of cheetah habitat each year. In 2012, with support from the Clinton Global Initiative, CCF expanded its BUSHBLOK™ production and is leading the way for an emerging biomass industry in Africa.

Nowadays, conservation priorities in each country where the cheetah is found are under evaluation. According to Dr Laurie Marker, founder and executive director of CCF, ensuring a future for cheetahs requires enhancing the livelihoods of human communities that live alongside them. Her creative approach includes developing alternative income sources in eco-tourism and craft making, providing economic incentives for predator-friendly agricultural products, and training workers to make value-added products derived from livestock, like goat cheese or soap.

CCF recently initiated an eco-label programme to motivate farmers to peacefully coexist with cheetahs. Under CCF’s model, farmers who agree to practise predator-friendly livestock management become certified with a Cheetah Country Beef eco-label and receive premium prices for their meat. “This concept works very well for the tuna industry, which markets dolphin-friendly products with great success,” said Dr. Marker. “We think we can adapt this approach with beef producers to benefit the cheetah in Africa”.

To celebrate the 5th annual International Cheetah Day this 4 December, check out our gallery, which showcases a selection of cheetah images from some of the continent’s most prestigious photographers.

Learn more about the cheetah here

About the author

Dr Laurie Marker is one of the world’s leading experts on cheetahs. The founder and executive director of Cheetah Conservation Fund (CCF), an award-winning research, education and conservation institution dedicated to ensuring the long-term survival of the cheetah, Dr. Marker has worked with the species in Africa since 1974. In 1990, Dr. Marker established the not-for-profit fund and relocated from the U.S. to Namibia to dedicate her career to saving the wild cheetah. Now the longest-running cheetah conservation organisation, CCF has helped stabilise the population in Southern Africa and is considered a model for large predator conservation.

Dr Laurie Marker is one of the world’s leading experts on cheetahs. The founder and executive director of Cheetah Conservation Fund (CCF), an award-winning research, education and conservation institution dedicated to ensuring the long-term survival of the cheetah, Dr. Marker has worked with the species in Africa since 1974. In 1990, Dr. Marker established the not-for-profit fund and relocated from the U.S. to Namibia to dedicate her career to saving the wild cheetah. Now the longest-running cheetah conservation organisation, CCF has helped stabilise the population in Southern Africa and is considered a model for large predator conservation.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()