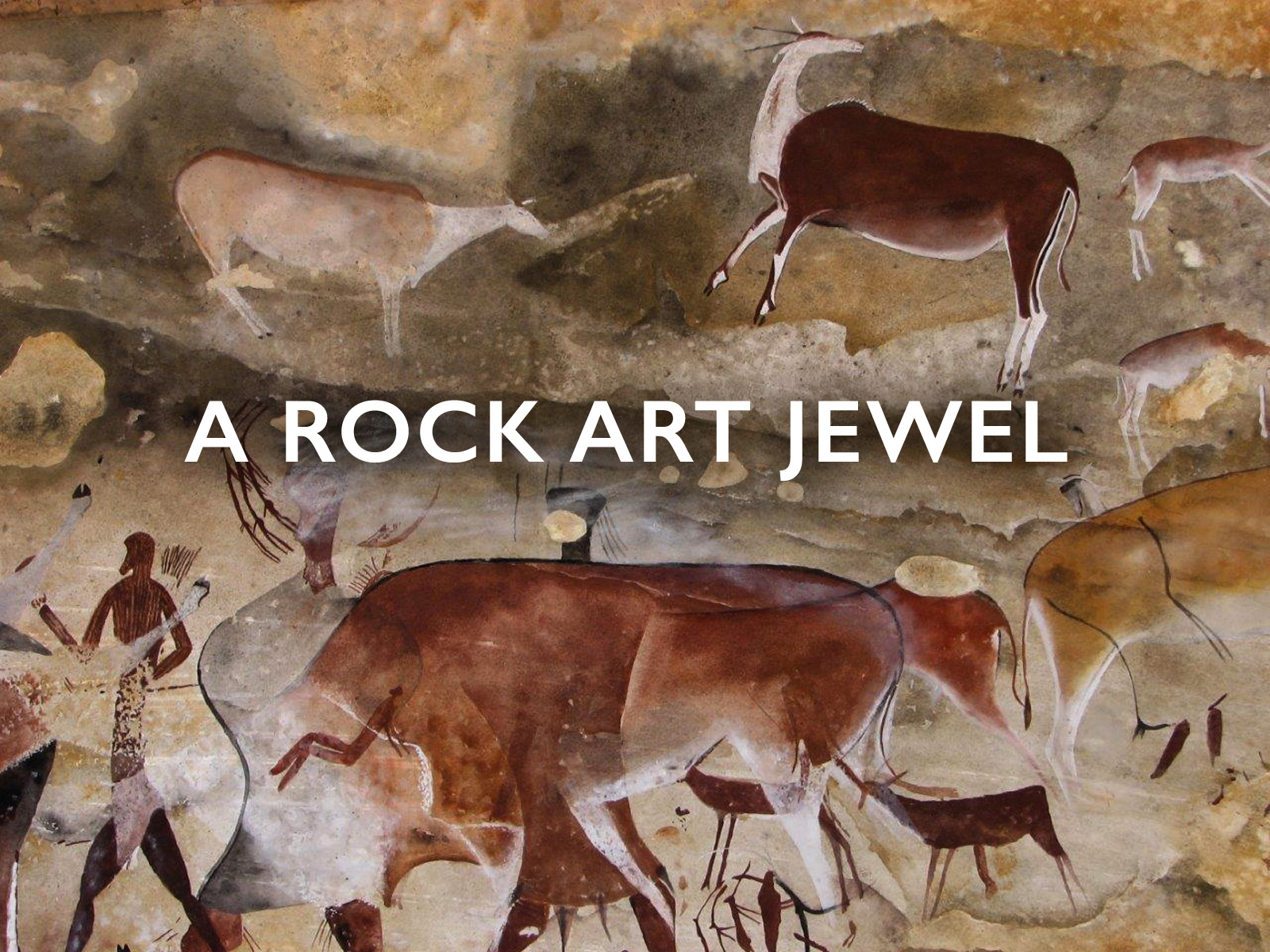

AN ARTIST RETURNS TO THE ANCIENT METHODS OF THE SAN

In 2009 I was commissioned to document a complex rock art panel on the roof of a shelter in a remote area of South Africa’s Drakensberg Mountains. The area is out of bounds to the general public and required me to visit the site on three occasions to capture all the relevant information from the rock surface. During this time, it occurred to me again just how observant and skilful the early San artists were regarding their understanding of paint and implement making. This, combined with the rich and detailed imagery and symbolism they had represented on the rock, made for a challenging and absorbing project. The Christmas Shelter project has definitely been one of the highlights of my painting career, and I owe a great deal of gratitude and appreciation to the people who made it possible.

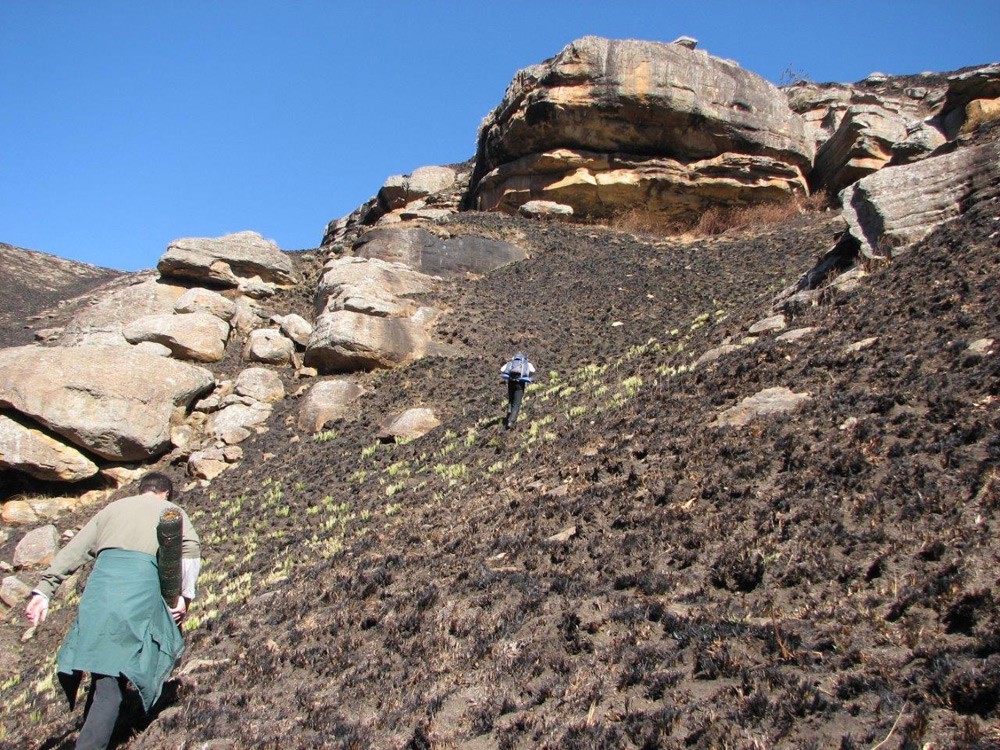

The team climbs the slope leading to the Shelter after fire swept through the area. Fire is just one of the elements that adds to the deterioration of Southern Africa’s exposed rock art.

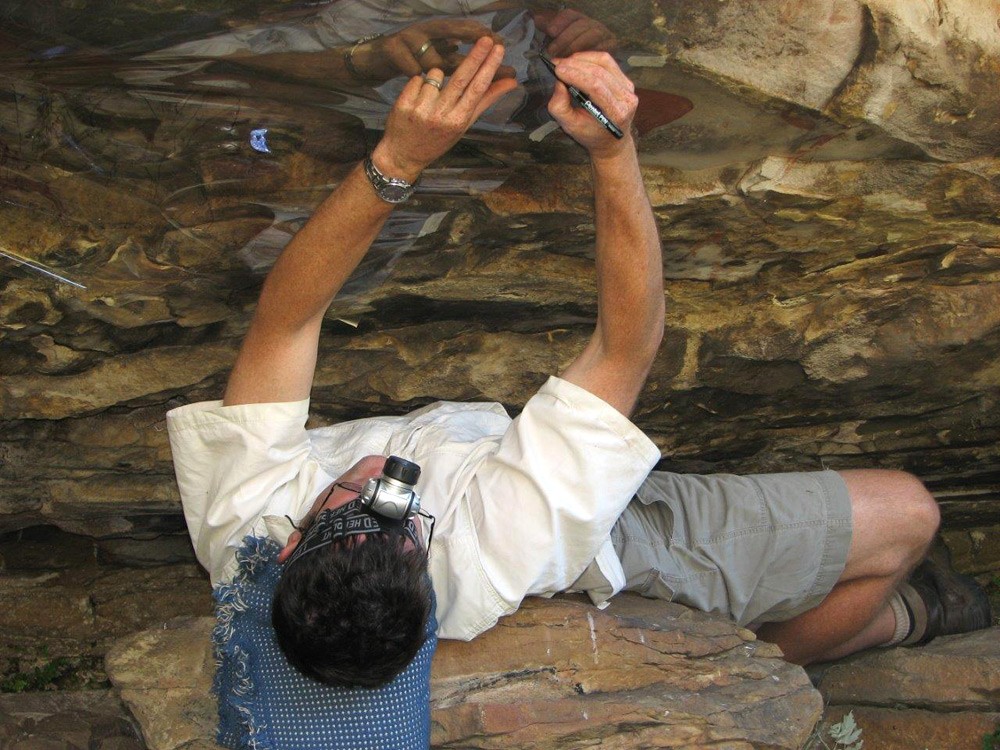

The author colour matching on site. ©Stephen Townley Bassett

Paint and brush material was sourced from animals hunted nearby

Years of weathering and layers of surface deposits, like dust and salts, can obscure detail in the art that is only made clear by close inspection with magnifiers and lighting. The tracing process allows one to capture this detail very accurately. It is a slow and painstaking process and only years of practice enables one to more clearly ‘read’ the often faded imagery. I have often taken visitors to sites where imagery is faded, only to be told they cannot ‘see’ much on the rock. But after time at the site, and with assistance in ‘piecing’ together the faded motifs, they exclaim that they see much more and enthusiastically re-examine other sections of rock they had passed over moments before.

To accurately record the images at Christmas Shelter, I needed to draw from my stock of existing ochres and search for new materials in the landscape. During this time, I shot a blesbok and two ground squirrels. I divided the meat between myself and my staff, and the hair from these animals was a source of paintbrushes that I made and used for the project. I used strands from the tendons of the blesbok’s forelegs to bind the hairs onto wooden paintbrush shafts. The blood, a very good carrying and binding agent for dry pigment, was also used in the paint-making process. Combined with egg and plant juices from certain succulent plants, these two components make a very good paint.

Stephen works on documentary art.

The team hold the documentary art up for comparison with the original panel. ©Stephen Townley Bassett

‘I often felt like it was cracking the code of the rock’

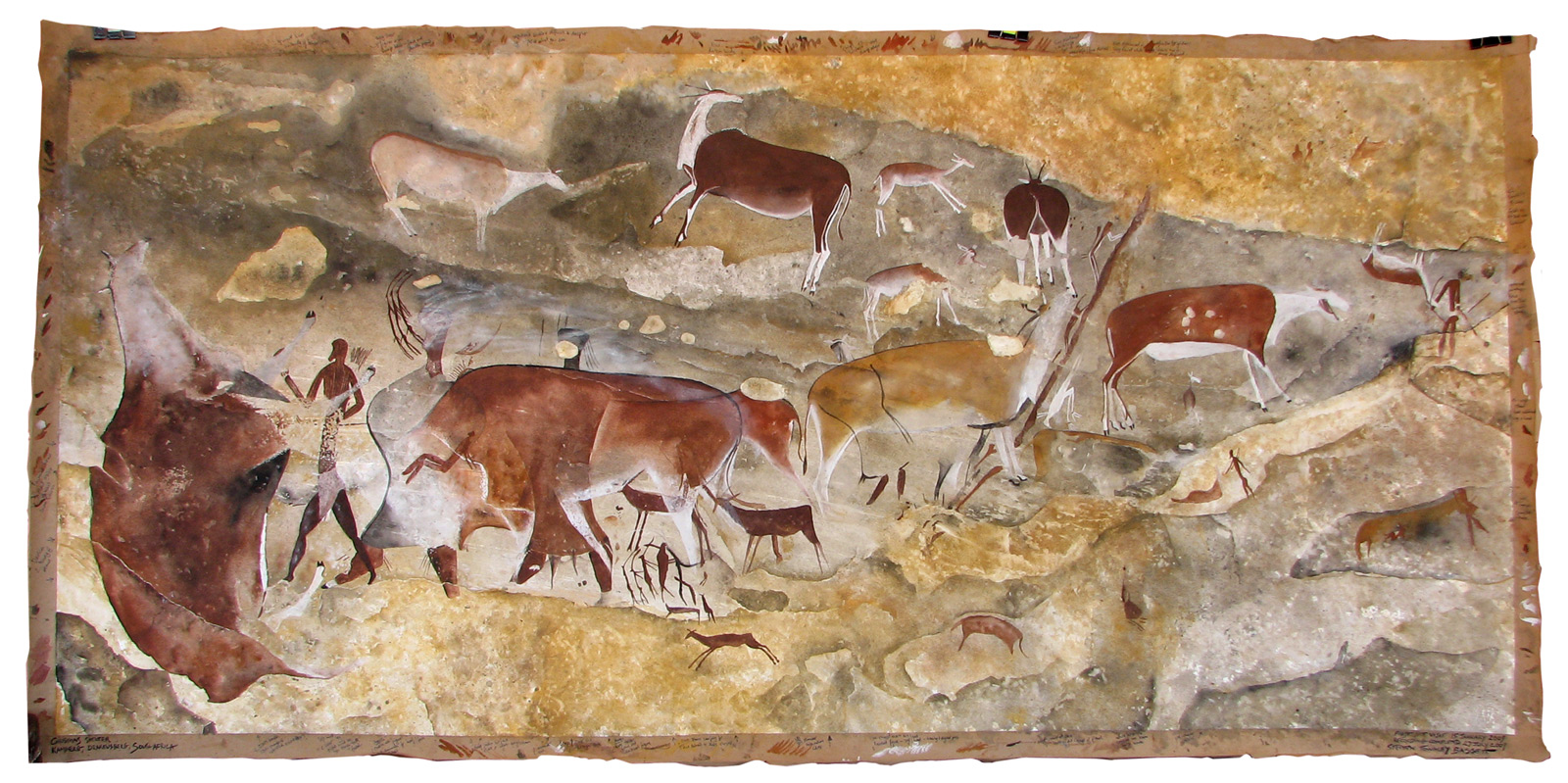

Completing the final documentary artwork depicting the Christmas Shelter panel took six months. I spent many hours at the site meticulously tracing the images on the rock face and colour-matching the various hues and tonal variations in the rock. Steps, cracks, undulations and exfoliated segments must be noted and recorded. On occasions, the unfinished work was taken to the site as a work-in-progress comparison to ensure I captured the feel of the rock. I often felt like it was cracking the code of the rock – that is to say, getting the right mix of techniques and colours that would accurately reflect the rock surface I was trying to depict on canvas. Once the code was worked out, I always felt a surge of energy and confidence regarding the way I would tackle the rest of the scene.

The creation of the panel required all my years of skill and experience in documenting rock art. Many different methods and techniques were used to faithfully recreate both the rock background and the imagery that had been placed there.

A description of the Christmas Shelter Documentary art.

The idea that rock paintings can best be interpreted in terms of the rich cosmology and religious beliefs of the people who did them is a strongly held view by contemporary researchers. Rock paintings, apart from their intrinsic beauty, played an integral and crucial role in the life of these early communities. Through the paintings, communication with the past and the spirit world was possible. The rock surface was seen as a veil between the real world and the spirit world. It was in these two worlds that one animal dominated the minds of the painters more than any other and that was the eland. It was greatly admired and revered by the San and is the most painted antelope in San rock art in South Africa. There are at least 8 clearly definable images of eland in the Christmas Shelter panel. On the left side of the panel, a large eland in red and a human figure, dominate this section. The upper torso and head of the human figure has been painted between the forelegs of the eland. It appears as if the human figure is touching one of the forelegs of the eland. Behind this figure are three nested, ethereal looking male human figures with what appears to be red lines extending from their heads. The San Shaman spoke about a potency boiling up inside him and exiting through the head or neck region. Middle right of the painting there is a beautiful image of an eland from the rear in a foreshortened position. The fat on both eland and San women was believed to have great potency.

Returning to the old ways

I saw my first San painting at 14 and asked questions that many people must ask when seeing the art for the first time: Who made them, how old are they, what do they mean, and what did the artists use to create them? I was with my uncle, ‘Ginger’ Townley Johnson, then. Having lost my father at a young age, I found myself drawn to this adventurous relative. A well-liked, humorous and eccentric man, he had become interested in rock art through his father, Frederick Townley Johnson, who had been looking for rock paintings in the Oudsthoorn district of the Southern Cape since 1910. In time, Ginger and his two friends, Hyme Rabinowitz and Percy Sieff would rediscover and document hundreds of sites throughout South Africa and particularly the Cederberg mountains in the Western Cape. Their work began in the 1950s and continued through into the early 1990s. These records would eventually become part of much larger databases at universities and museums in South Africa.

‘It was the technology behind the paintings that beckoned me most’

One of my uncle’s principal concerns was the art’s vulnerability to natural weathering. Unlike the deep limestone caves of western Europe, where rock paintings are mostly shielded from harsh wind, sun and rain, the majority of sites containing rock paintings in South Africa are in shallow caves or underexposed rocky overhangs. This, coupled with damage to the art by people and livestock, motivated my uncle to develop a method of recording the images onto paper using various techniques. I accompanied him on many field trips and watched him work at rock art sites and his studio in Llandudno. I was fascinated by how he would accurately re-create images we had seen weeks earlier and in rock shelters hundreds of miles away. Of the questions above about art, it was the last one that intrigued me most. While the meaning and age of the images were important to me, questions about the technology behind the paintings beckoned me the most. It came to me very clearly one day that I, too, wanted to continue in my uncle’s footsteps by locating and documenting this fragile and irreplaceable art legacy. However, instead of using commercially available paints as he was doing, I resolved to make my own paints and implements from materials I would collect in the landscape in which I so often walked.

‘I would need to discard the tools I was using and begin a kind of experimental archaeology’

I found little in written records on how early cave artists made their paintings. If I wanted to show what cave artists might have used to create their art, I should make my own implements and paints and duplicate their paintings using materials and methods that would have been available to them. This meant attempting to think as an early cave artist would have thought. I would need to discard the tools I was using, like pocket knives, spatulas, plastic and metal containers and commercially available brushes, and begin a kind of experimental archaeology. I had already decided to make art my livelihood, and this new path seemed like the beginning of a new adventure. So, apart from using a rifle to shoot an animal, all other processes would be accomplished using what I could find in the veld.

Some mountain slopes yielded various ochres that I could use as a pigment base. Others yielded a dark grey stone that, when struck against another stone, yielded a very sharp cutting edge. A gemsbok horn, when cut into segments with end caps made from the dried scrotums of a grey rhebok, made a good holding vessel for my delicate feather-tipped brushes. A giraffe’s knee cap component makes an excellent, lightweight holding vessel for mixed paint, naturally hollowed small loose rocks make excellent paint pots, and scapulas from animal skeletons bleached white by the sun make good mixing surfaces. The landscape around me became a veritable supermarket for tools and materials.

Colours from rock and bone

I learned that there are four basic pigments that early cave artists had at their disposal. Mineral pigments, such as red and yellow ochres, are iron-rich clays and present as soft or semi-hard rock that can be ground into fine powder to form a durable paint base. The other two pigments are white and black. White comes from white clay, kaolin, raptor droppings or burnt eggshell and bone, and black comes from charcoal and manganese oxide. I divided the painting process into three stages. Firstly, identifying pigments and their manufacture into a workable paint using various binding and carrying agents. Secondly, the collection and/or manufacture of vessels to hold the pigments and mixed paint. Thirdly, an array of implements would enable me to apply the mixed paint to the surface of the rock.

Heating eggshell and bone to create white pigment. ©Stephen Townley Bassett

The eland antelope featured in several San rituals and ceremonies, such as the eland bull dance, marriage and other rights of passage. ©Chris Hills

‘I have found that different animals yield different quality brushes’

Over the years, I have found that different animals yield different quality brushes, and hair from different parts of the animal can yield different types of brushes. Different brushes would, in turn, have different uses or applications at the rock face. Feather-tipped brushes are not as durable while making good painting implements and do not hold as much paint as a bristle brush. During my rock surface trials, I found that fat and egg make good binding agents. Animal blood and sap from certain plants, such as the euphorbia species, can also bind. In contrast, saliva, water and animal gall are good carrying agents (i.e. they hold the finely ground pigment particles in suspension, allowing the paint to be drawn out on the rock surface).

Flat stones can be used as mixing surfaces or as heating stones. Animal bones, hooves and horns, stone paint pots, and plants (i.e. small calabash) are all important utensils when painting at the rock face.

When confronted with beautifully rendered polychrome roof paintings and tried to do the same with elementary implements like chewed sticks and quills, I realised that more sophisticated implements must surely have been used. These were those ‘Aha…’ moments when one sees things differently. The paint mix and viscosity must be just right; the painting implement should be of such a construction that relatively large amounts of paint could be held in a reservoir of some kind to be released onto the roof of a shelter in the correct manner.

South Africa’s immense rock art gallery

Broadly speaking, South Africa’s geology is a great horseshoe of mountain ranges surrounding a relatively flat hinterland. From the Gifberg mountain ranges in the west to the Makabeng Plateau in the northeast, one can find rock paintings in thousands of caves and rocky overhangs. The Drakensberg mountain range is particularly rich in rock art. With its abundant rainfall and plentiful supply of flora and fauna, San communities inhabited these mountains for thousands of years, and over time there was significant contact and cultural exchange between San groups and Bantu herder communities that moved into the region. This is evident in many aspects, one being language. The clicks in various Nguni-speaking languages originate in contact with San communities.

In 2005 I was fortunate enough to work on a project with an old man named Kerrick Ntusi, who had both Sotho and San genealogy. Kerrick was an initiation leader in his younger days and always wanted to complete a “healing of the land ceremony” for his people and his forbears. He could remember his grandfather painting in a cave in Lesotho, and I was tasked at the time with recording in the paint under instruction from Kerrick, on a sheltering wall in KwaZulu-Natal, the images that he could remember from his birth cave, as part of this ceremony. This was an extraordinary experience for me and one that I will always remember.

Where to see the art

Researchers in other countries, such as Australia, have found that it is better to only open two or three to the public in an area where there may be ten painted sites. These are termed “sacrificial sites”, and although they are both monitored and managed, they nevertheless are susceptible to vandalism by the public. This management policy safeguards the other seven or eight sites that are not open to public viewing. This is the case with Christmas Shelter.

Two primary places of interest for the public to learn about rock art and view it are the Didema Rock Art Centre in the Cathedral Peak area and the Kamberg Rock Art Centre in the Nottingham Road area.

Within two hours walk from the Kamberg Rock Art Centre is the world-famous Game Pass Shelter site open to the public. Visitors must be accompanied by a guide, who one can arrange through the Kamberg Rock Art Centre. On route to Game Pass Shelter, one passes the much smaller Waterfall rock art site, which also contains several rock art images.

Today, the Christmas Shelter documentary artwork hangs at the Rock Art Research Institute at Wits University, Johannesburg. Who knows when more of the panel will exfoliate from the cave ceiling and be lost in the accumulated debris of the shelter floor? The heat from periodic veld fires through the area will certainly accelerate weathering. In some small way, at least a moment in the painting’s life has been captured and is encapsulated behind glass in a building in Johannesburg for visitors to see.

An exhibition, “Tracing the Cosmos – follow the brush strokes of the cave artists”, runs from 24th June to 30th August 2015 at the Origins Centre, Wits University, Johannesburg. The Christmas Shelter artwork will form part of this exhibition.

About the author

STEPHEN TOWNLEY BASSET was born in Cape Town, graduating from the University of Cape Town with a Bachelor of Social Science degree. He is the third generation in his family to be involved in the location and documentation of rock art in Southern Africa and is today a specialist in the field. His primary interests lie in the accurate, full-colour documentation of the art and research into pigments, paints and implements used by early hunter-gatherers of the region. Stephen consults with farmers and landowners on the conservation and management of sites. He is regularly involved in rehabilitating rock art sites and removing graffiti from vandalised sites.

STEPHEN TOWNLEY BASSET was born in Cape Town, graduating from the University of Cape Town with a Bachelor of Social Science degree. He is the third generation in his family to be involved in the location and documentation of rock art in Southern Africa and is today a specialist in the field. His primary interests lie in the accurate, full-colour documentation of the art and research into pigments, paints and implements used by early hunter-gatherers of the region. Stephen consults with farmers and landowners on the conservation and management of sites. He is regularly involved in rehabilitating rock art sites and removing graffiti from vandalised sites.

Stephen lives with his wife, Karen, and their two children in Queenstown and has recently relocated his gallery and studio to the town of Cathcart on the N6 between Queenstown and East London in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa. At this studio and gallery, he will set up a display of the pigments, paints and implements both sourced and used for his paintings. Both original artwork and various limited edition art prints will be sold from this location.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()