Zanzibar, the jewel of the East African coastline, has it all. With beautiful beaches, fascinating history and cultural influences from Europe to Asia, Zanzibar has an old-world charm that is unique in Africa. But how did this cultural melting pot come into being and why is the dhow such an integral part of that history? Written by Andrew Hofmeyr

Many influences from across the Indian Ocean are woven together in Zanzibar, but to really understand the movement of people, languages and cultures through this enchanting entrepôt, you need to look no further than the dhow.

Traditional dhows

The Swahili word ‘dhow’ is a generic term for the pre-European ships of the Indian Ocean. Traditionally, these dhows were sewn together using coconut coir (fibre) – a medieval practice born from the belief that magnets under the sea would suck any nails out of a vessel, thus condemning the crew to certain death beneath the waves. The dhows are typically rigged with a lateen sail, a classic triangular sail attached to a crossbeam, raised and lowered according to the wind. These boats range in size from small fishermen’s boats to vessels over a hundred feet long!

The Baggala, for example, is an ocean-going dhow with a curved prow (the front) and an ornately carved stern (back) and usually has two lateen sails. The Boom vessel, on the other hand, is curved at both ends with a single large sail in the middle and was preferred by sailors from the Persian Gulf. It is believed that these boats have moved around the Indian Ocean for thousands of years, carrying sailors from the Arabian Peninsula along the East African coast to India and, some believe, even as far as China.

Although many deep-water ships existed, the dhows were predominantly used for coastal trade. Moving up and down the East African coast, the dhows stopped at ports along the way, trading goods and ferrying passengers. Before the onset of steam and later petrol, these wind-powered ships were the cornerstones of a pulsating and cosmopolitan ocean trade. The constant movement of tradable goods and diverse people also meant the exchange of ideas, technologies, and religion.

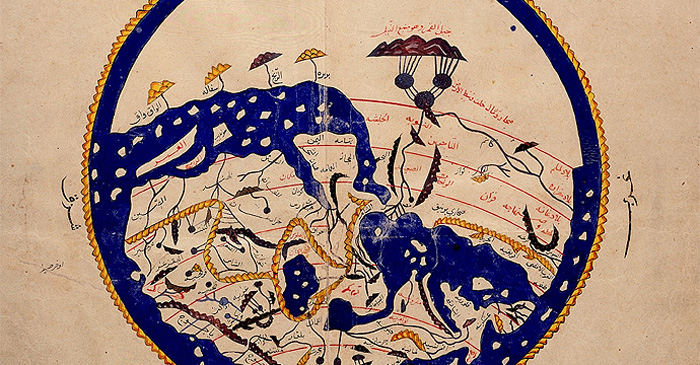

The ancient dhow trade is recorded in the book The Periplus of the Erytraen Sea. Written in the first century by an unknown Greek author, the Periplus guides the ports, people and trade goods of Arabia, India and the East African coast. The existence of this little book suggests a trade route that has continued for thousands of years as empires rose and fell around it. A hint of its sustained importance over the centuries lies in the seasonal monsoon’s function.

Ecology and the monsoon winds

The Indian Ocean dhows sailed according to the monsoon trade winds that enabled the movement of goods between rich but completely different ecological zones. The lush tropical zones of East Africa and Madagascar were an important source of timber, gold and ivory, while the nutrient-rich waters surrounding the desert zones of North Africa and the Arabian Peninsula were abundant in pearls, fish and dates.

In January, the northeast monsoon carried dhows laden with dried fish and pearls south from Arabia. In July, after nearly six months, the cycle reversed, and the southwest monsoon would blow the dhows, having collected ivory, timber and gold back to Arabia. The combination of the seasonal monsoons, extended layovers and the need to trade between the different ecological zones created the ideal conditions for developing a complex and cosmopolitan society.

Zanzibar and the Indian Ocean

Zanzibar is particularly unique as it was not only the last port of call for the Arabian dhows before sailing the treacherous waters of the Mozambique Channel, but it was also the destination of larger, open ocean ships sailing from the Malabar coast of India. A seafaring culture that saw sailors staying for extended periods of time (up to six months waiting for the monsoon winds to change) meant that Zanzibar developed as a cultural hub. Sailors from all around the Indian Ocean gathered together, mixing religion, language and culture, and it was not uncommon for sailors to take wives and start families, thus deepening the bonds between otherwise distant locations.

These ancient ties were further strengthened by the unification of Islam under the Abbasid caliphate in the 9th century. Some historians note this era of peaceful trade and the spread of Islam as the “Era of Sindbad” – a nod to the importance of maritime trade and commerce in history. This era of a legendary figure—Sinbad the Sailor—lasted until the arrival of the Portuguese in the late fifteenth century, heralding a shift in the culture of the Indian Ocean.

Old Stone Town

Zanzibar, as the cultural nexus of this Indian Ocean trade, holds the evidence of this diverse and exciting history in Stone Town. It is the only functioning historic town in East Africa, and its remarkably well-preserved architecture (mainly from the 19th century) bears the mark of Swahili, Arabian, Persian, Indian and even European influences. In 2000, Stone Town was listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site due to its diverse historical and cultural influences.

Old Stone Town is the perfect place to soak up the old-world charm of Zanzibar, with its winding alleys, bustling bazaars, grand merchant houses and mosques calling to be explored.

Find your next African safari here – ready-made or ask us to build your dream safari

Find your next African safari here – ready-made or ask us to build your dream safari

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()