When all else fails

![]()

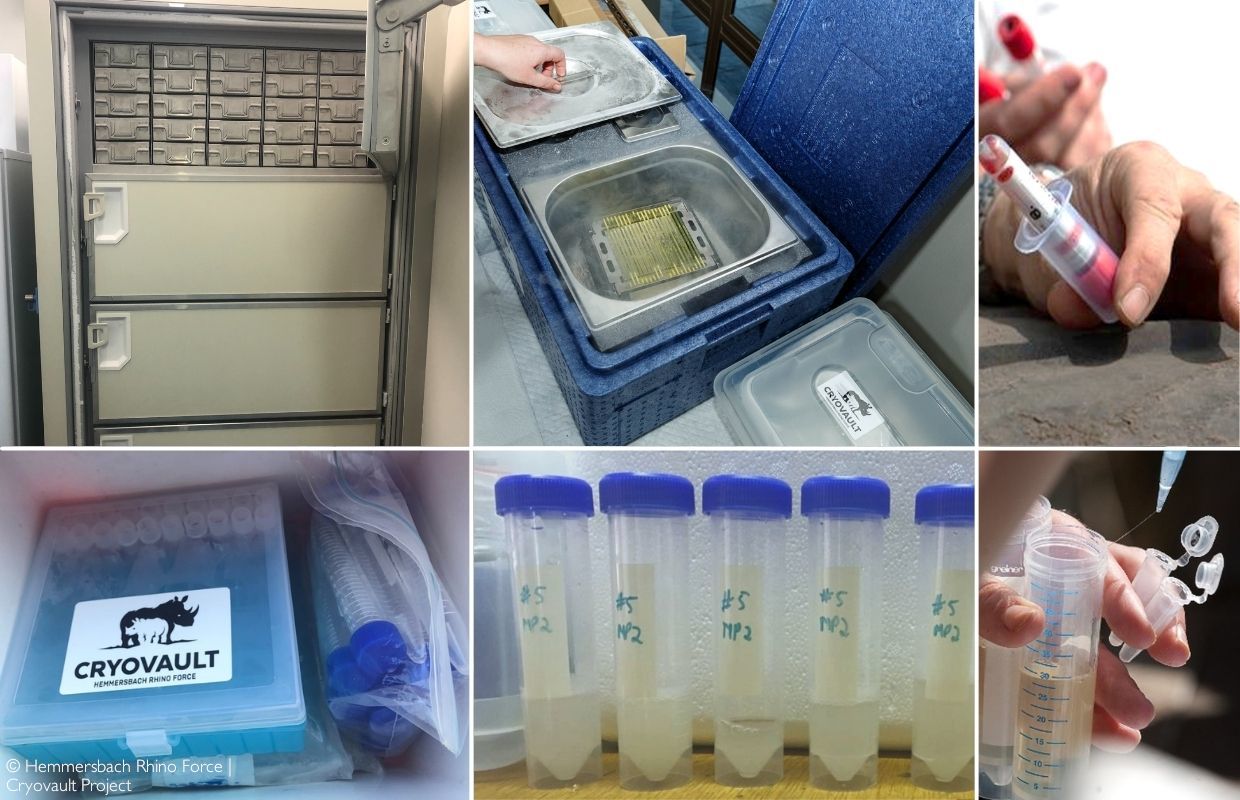

The rhino Cryovault is a biobank that holds the largest genetic repositories of rhino DNA, gametes, and tissues in the world; frozen and preserved indefinitely. What does it mean to save a species? What happens if, in the absolute worst-case scenario, we fail? While Hemmersbach Rhino Force is doing everything in their power to make sure that does not happen, they do have one last ace – the rhino Cryovault.

In every cell of every organism, from the smallest bacterium to the hugest blue whale, four unique, organic molecules (nucleic acids) are arranged in their millions to form a genetic blueprint that dictates the organism’s – shape, potential size, dietary needs, reproductive proclivities, propensity for language, eye structure – the list is nearly endless. Within the DNA double helix, this code holds most of the secrets to the diversity of life as we know it. Every time a rhino is poached, an entirely unique genetic fingerprint is lost.

What is genetic diversity?

The term “biodiversity” has become very popular since first introduced in scientific publications of the 70s. By now, most people understand that the foundation of conservation rests on protecting biodiversity. Biodiversity refers to the variety of species in an ecosystem, their ecological complexes and their interactions within an ecosystem. The third level of biodiversity is a measure of the variety of genetic characteristics within a species – genetic diversity.

It should be relatively self-explanatory why genetic diversity is of fundamental importance to the survival of a species. In the long-term, genetic diversity underpins one of the cornerstones of evolutionary theory. Genetic differences translate to certain traits that allow some organisms to breed more successfully than others – survival of the fittest. Greater genetic diversity within a species enables adaptation to changing environments (think climate change) and confers greater disease resistance to the species as a whole.

Conversely, as individual numbers of a species decrease, inbreeding will result in a loss of genetic diversity, which will decrease a species’ robustness in the face of new challenges (parasites, climatic changes etc). Inbreeding can also cause ‘inbreeding depression’, which is the reduced biological fitness of a population. This can lead to severe genetic defects, reduced fertility and even infertility. In essence, when humans decimate biology (animals, plants, mushrooms etc), we are not only destroying individuals and their potential genetic legacies, but we are also reducing the species’ capacity to recover and overcome adversity.

Hemmersbach Rhino Force

Enter Hemmersbach Rhino Force, a direct action conservation organisation dedicated to safeguarding Africa’s remaining rhinos. Their anti-poaching services are provided free-of-charge and utilise a combination of innovative tactics, cutting-edge technology and old-fashioned boots-on-the-ground to tackle wildlife crime in Southern Africa. Rhino Force is operational in the Greater Kruger region (where some 50% of poaching events in Africa occur). They work with local authorities, private entities and anti-poaching operations on everything from surveillance and intelligence to proactive prevention and forensic work. In addition, their Zambezi Black Rhino Project in Zimbabwe is geared towards restoring a wild haven for the reintroduction of black rhinos, once abundant before poaching devastated their numbers.

Rhino Force’s holistic approach to protecting rhinos includes extensive work with local communities, promoting education and employment and tackling anti-poaching through anti-poverty strategies. Improving living conditions, restoring and equipping schools, litter removal, and supporting community engagement are just some of the initiatives that the Rhino Force has thrown their weight behind.

However, the sheer severity of the rhino poaching crisis prompted the creation of the Hemmersbach Rhino Force Cryovault in 2018, a biobank of vital biomaterial including DNA and viable sperm. As unsettling as it is, we must face the reality that we may not be able to stem the tide of poaching. This proactive approach is intended to create a genetic backup before it is too late.

The Cryovault and Veterinary Unit

The Cryovault team consists of Dr Imke Lüders, a specialist veterinarian from Germany and Dr Janine Meuffels, a veterinarian from South Africa. The team members all have long-standing backgrounds in animal reproduction and wildlife medicine. They are, at present, the most experienced team in Africa at executing large-scale gamete conservation projects. Together, they have successfully collaborated in collecting semen from elephants, giraffes, and rhinos, from both live (intra-vitam) and deceased (post mortem) animals in wild and captive situations.

As with any other Rhino Force projects, the Cyrovault is not a commercial operation. Instead, it provides specialist veterinary wildlife reproduction and biotechnology support services to other scientists, veterinarians and their clients. The laboratories are equipped with the resources necessary to evaluate gametes’ viability and store tissues, gametes, and DNA indefinitely through cryo-preservation.

The ART of reproduction

Assisted reproduction technologies (ART) including artificial insemination, in-vitro fertilisation and embryo transfer are techniques that have been used successfully for years, particularly in the agricultural industry with livestock. There is a perception that because these techniques have been so effectively applied in both humans and livestock, it should be simple to transfer them to wild species. However, this is far from the case. Every species has evolved a unique anatomy and reproductive physiology. Successful ART requires extensive research and the development of species-specific protocols. Unravelling secrets of ART for the African rhino species is the calling of the Cryovault team.

Theriogenology – which concerns the study of veterinary reproductive medicine and surgery – is a field subject to continual refinement. Conservation-minded reproductive specialists are continually searching for ways in which these techniques can be used to balance the odds for threatened species. Viable semen has been collected and cryopreserved, leading to successful artificial insemination (using both fresh and frozen semen) of elephants, giraffes, and southern white and Indian rhinos. However, most advancements in wild species have been made in captive settings where scientists have unrestricted access to the animals.

The Cryovault team continues to offer tremendous contributions to this knowledge base, and in 2020, they collected, processed and cryopreserved free-ranging (wild) black rhino sperm samples – a world first. They have teamed up with Eastern Cape Parks and Tourism Agency (ECPTA) for a three year project to collect and store samples from as many black rhino individuals as possible.

Where rhinos are concerned, the Cryovault team’s approach to gamete collection is largely opportunistic currently. When a live bull rhino is anaesthetised for a routine process such as a dehorning or ear notching, the team applies a low-voltage stimulation to the prostate gland in a process known as electroejaculation. In the case of poached, hunted, or euthanised animals, the testes are harvested in their entirety. Once the samples return to the lab, the viability of the sperm is tested and, if shown to be suitable, it is transferred to sperm straws and frozen using liquid nitrogen. It is even possible to separate the sperm cells according to whether they carry an X or Y chromosome, thus controlling the sex of potential offspring.

The process of ovum (egg) collection from a live female rhino is known as an ovum pick up. This is a highly specialised technique and requires the regulation of several physiological factors. The team can also harvest oocytes from deceased animals, but with only a six-hour window in which to do so. This is logistically complicated – with a low success rate.

Managed wildlife breeding – a conservation tool

What does this science mean for the future of our rhinos? The reality is that there are few self-sustaining wild rhino populations left throughout the world. In South Africa, home to most of Africa’s rhino, roughly a third are privately owned. Most of these populations are already intensively managed. Suppose the captive growth rate, and the poaching rate continue along the same trajectory. This eventuality could quickly shift the proportion of privately-owned rhino to 50%. The onus will be on private owners to protect the remaining rhinos. Intensive breeding management programmes are an inevitable part of a survival plan for a species approaching the brink. Accepting that rhinos are on that list must happen sooner rather than later.

One of the primary objectives is for the Cryovault facility to be the largest of its kind for African rhino genetics. This massive archive will contribute enormously to DNA population genetics research and act as a reference database for the species. Most importantly, it can be applied to both current and future rhino breeding. Expanding our collective knowledge of rhino reproductive physiology, gametes’ parameters and developing protocols for successful, repeatable methods of assisted reproduction that can be applied to rhinos, is of paramount (and urgent) importance.

Back from the brink (again?)

In the past, the call for reproductive specialists to save a species on the brink has generally come far too late, when just a few individuals of the species remain. Developing appropriate techniques and protocols at this stage is impossible, and the rhino Cryovault team is entirely focussed on ensuring that this time, the approach is a proactive one.

While it may be impossible to freeze time, the Cryovault offers the next best thing – a way to ensure that, in the worst-case scenario, we can preserve some of the genetic legacies of our rhinos before they are lost forever.![]()

[Hemmersbach Rhino Force is one of the two direct action projects of the social purpose IT company Hemmersbach, driven by a desire to fight injustice where authorities fail. Hemmersbach does this through Direct Action: their projects and actions are purely self-financing and reliant on the commitment of their team members, without the need for external donations. Hemmersbach is committed to using 20% of the company’s annual profits for these Direct Action projects, directed towards a good cause with the assurance that this revenue is focused where needed.]

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()