Resilient, family-loving, fortified rodents

As African mammals go, the Cape porcupine (Hystix africaeaustralis) is perhaps the least ambiguous in its message to the world around it – for a creature with a crest of spines, some of which are over 50cm in length, social distancing was never going to be a challenge. Yet despite their somewhat antisocial look, these fortified rodents have a surprisingly family-oriented approach to life and, if left alone, are relatively innocuous in their existence. Retiring and elusive, it is often only their family-shared attraction to human rubbish that alerts surrounding people to their presence.

The basics

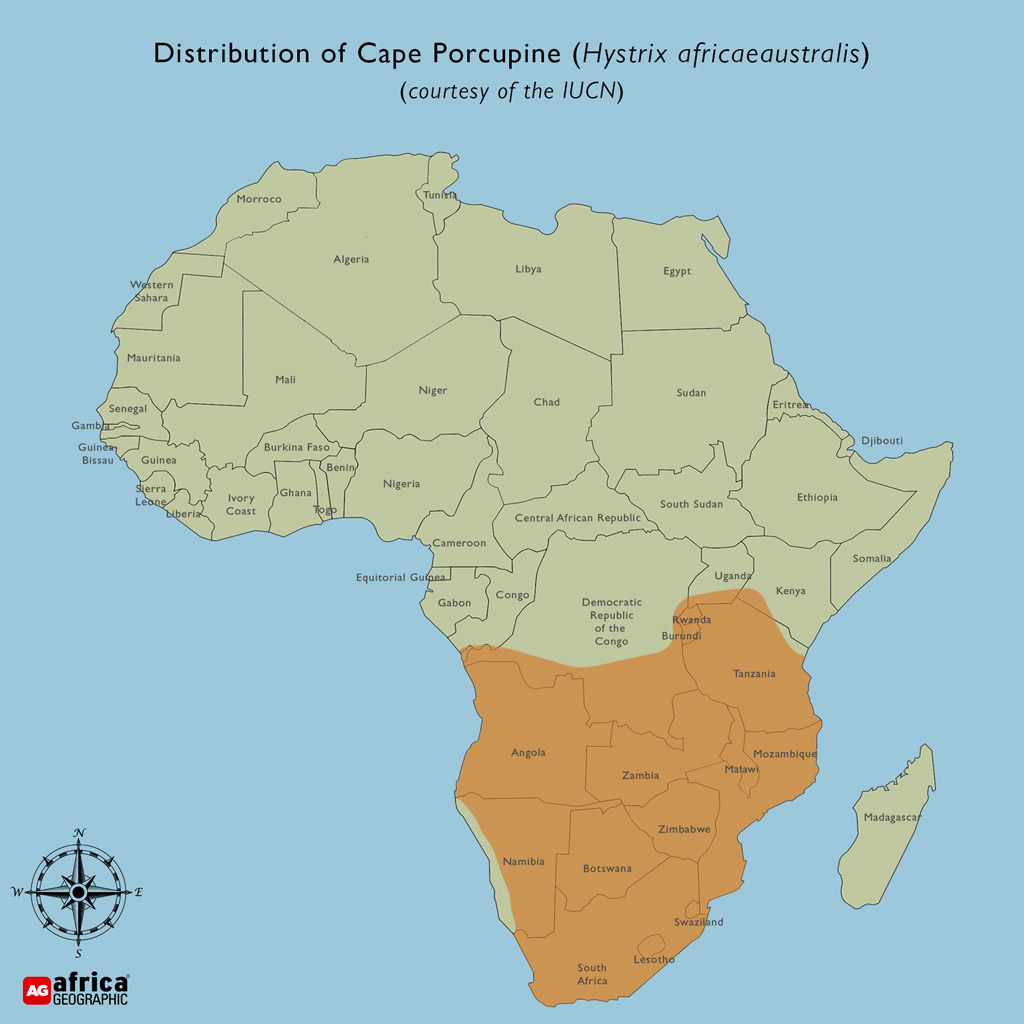

Cape porcupines are the largest rodents in Africa and the fourth largest in the world after South America’s capybaras and North American and Eurasian beavers. The largest Cape porcupines measured have weighed more than 30kg, though most weigh around 20kg, with minimal size difference between the males and the females. They are found throughout Southern, Central and East Africa in a wide range of habitats from deserts to forest, and live for over 10 years in the wild. At present, Cape porcupines are listed as being of “least concern” by the IUCN.

They are stocky and powerfully built creatures with short limbs, and while they can bustle off at a fair pace if disturbed, porcupines clearly do not rely on speed or camouflage as part of their predator avoidance strategy. Instead, it is their significant armoury that keeps them safe – a strategy effective for all but the most determined or foolish of predators.

The weapons

Their black-and-white quiver of quills is an example of aposematic colouring – contrasting colouration used to warn would-be predators to think twice about attacking. This is combined with specially modified hollow quills that the porcupines use to make a startling rattling sound when threatened. If these warnings are ignored, porcupines are not afraid to use these spines, sometimes to deadly effect. The quills themselves are essentially modified, hardened hairs and they come in several different shapes and sizes that all form part of the same defence system. The longest of these tend to be quite thin and flexible – the perfect tool for poking at vulnerable eyes and making it extremely difficult to get anywhere close to the porcupine’s body. A second set of quills set in clusters around the porcupine’s back and tail are shorter and thicker, creating a powerful barrier of spears that are used for precisely that purpose.

Despite the general misconception to the contrary, porcupines are incapable of shooting their spines at would-be attackers like some kind of archer. Instead, their technique when threatened is to stiffen their quills away from their bodies, forming a protective shield around their backs and then, if necessary, they reverse at high speed into their attacker. The ends of their quills are highly barbed at the tip, which enables quick penetration but makes removal extremely difficult and it is not all that uncommon to see leopards or lions with quills deeply embedded within their flesh. Though rare, these painful injuries and subsequent infections can prove fatal.

This stab-and-retreat approach is effective as a deterrent – most predators will back off from confrontation. That said, lions and leopards can and do kill porcupines, though in the case of lions this is unusual behaviour only seen in curious adolescents or particularly hungry individuals. Young leopards also find themselves attracted to the allure of such slow-moving prey and some develop unique strategies that allow them to become porcupine specialists. Using their finely honed ambush skills, these porcupine enthusiasts aim for the head before the porcupine has time to fire up its defence systems.

Fascinatingly, spotted hyenas very seldom bother to harass porcupines. In areas with high availability of prey (without such thorny exteriors), hyena cubs and porcupines sometimes share the same set of burrows. However, the rambunctious hyena cubs usually send their neighbours packing eventually. As diurnal animals, warthogs tend to make better roommates, returning to the burrow just as the porcupines are getting ready to depart. Unless there has to be an unfortunate mistiming of entry, these arrangements tend to be largely without incident.

Diet and behaviour

Porcupines are almost entirely nocturnal, emerging from their underground burrows at dusk to set off in search of a mostly plant-based diet, ranging across a territory that can be over 200 hectares in certain areas. As previously mentioned, porcupines do display a particular proclivity for raiding human habitation in search of tastier meals. Vegetable gardens prove to be a particularly attractive option and unless well-protected, will seldom survive long in an area where porcupines roam. Some individuals become so brazen that they have been known to enter houses, much to the bemusement and occasional surprise of resident humans and pets.

Thanks to their rodent incisors, the signs of porcupine feeding activity are easy to spot. They have a particular appreciation for the bark at the base of tamboti trees (Spirostachys africana), even though the latex secreted by these trees is extremely toxic to humans. Their foraging activities are not entirely limited to the vegetarian options, and they regularly gnaw on bones to supplement their mineral intake.

Reproduction

Porcupines are monogamous, and both the male and female play a role in raising and protecting their young (known as porcupettes – watch this cute video). The pair mates regularly (and carefully) throughout the year, though the female typically only has one litter each year, usually during the wet season. The average number of offspring is one porcupette, but there can be up to three in a litter, born with soft quills that harden a few days after birth. The young spend their first few weeks close to the safety of a set of burrows before they are old enough to accompany their parents on foraging excursions. They reach sexual maturity at around a year old, and both the males and females disperse from their natal groups once mature.

Resilient through and through

Even though they are sometimes hunted and eaten in the bushmeat trade and their quills are used for both ornamental purposes and traditional medicine, overall Cape porcupine numbers remain stable for now. There are regions where they are more likely to be persecuted, particularly in farming areas where their dietary preferences and ability to dig under fences do little to endear them to their human neighbours. Yet, like many members of the rodent family, Cape porcupines have shown themselves to be both resilient and adaptable to the ever-encroaching human impact on their natural habitats.

Resources

For an endearing, tearjerker of a story, read our account of this Cape porcupine who was treated and released after being burnt in a fire.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()