Quotes from poachers:

“I just wanted to send my first-born child to school so that he could get an education and be different from me. I wanted him to have the opportunity which I was denied as a child.”

“What attracted me most is that they were living a good life, they had nice houses, and they could afford anything they wanted, whenever they wanted it. I wished for that. One day I went to the tavern with a person who poaches rhinos. We met some other people there. The way they were behaving made me look like I am not man enough because I couldn’t afford what they could. I was turned into a laughingstock in my community.”

“But you know, if I were working, I would not have gone and done this. It’s just sometimes when you are in [a] tough situation; you resort to desperate measures.”

Who are the poachers feeding the illegal wildlife trade and what motivates them? These are fundamental questions that should shape the policies surrounding the fight against illegal wildlife trade but are often dismissed or overlooked. Calling for increased security measures and harsher sentences is the inevitable rallying cry but understanding what motivates a person to enter the world of wildlife crime is equally vital. Now a new report by TRAFFIC investigates the driving factors of poaching activities and how policymakers might go about addressing them, introducing a more nuanced perspective of the first step in the trade in animal parts.

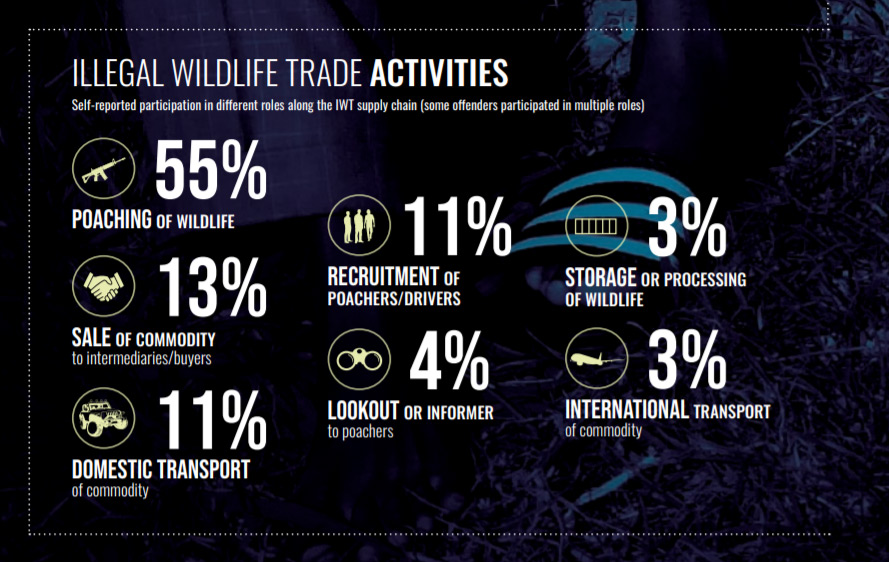

The report indicates that over the past ten years in South Africa alone poachers have taken over 8,000 rhinoceros for their horns, illegally harvested 96 million abalone between 2000 and 2016, and that the illegal trade in cycads is considered the main threat to their survival in the wild. TRAFFIC’s investigation focussed on incarcerated individuals convicted of crimes in the illegal wildlife trade (mostly poaching) in South Africa, a country considered to be key in the illicit trade in wildlife due to the role it plays as a source, transit and destination country. Of the 73 interviewed individuals, 54 were serving sentences for rhino-related offences, 10 for abalone related crimes and 9 for roles in the illegal cycad trade. Of those poachers interviewed:

- 97% were male

- 48% were South African (the remainder were Mozambican, Zimbabwean and Chinese)

- 5% were aged between 29 and 35

- 83% did not have secondary education

- 38% were unemployed, and 36% had informal employment

- 54% were influenced by peer pressure

- 78% had at least one dependent

- 66% had sufficient income to cover only the day-to-day basics of food, water, and shelter

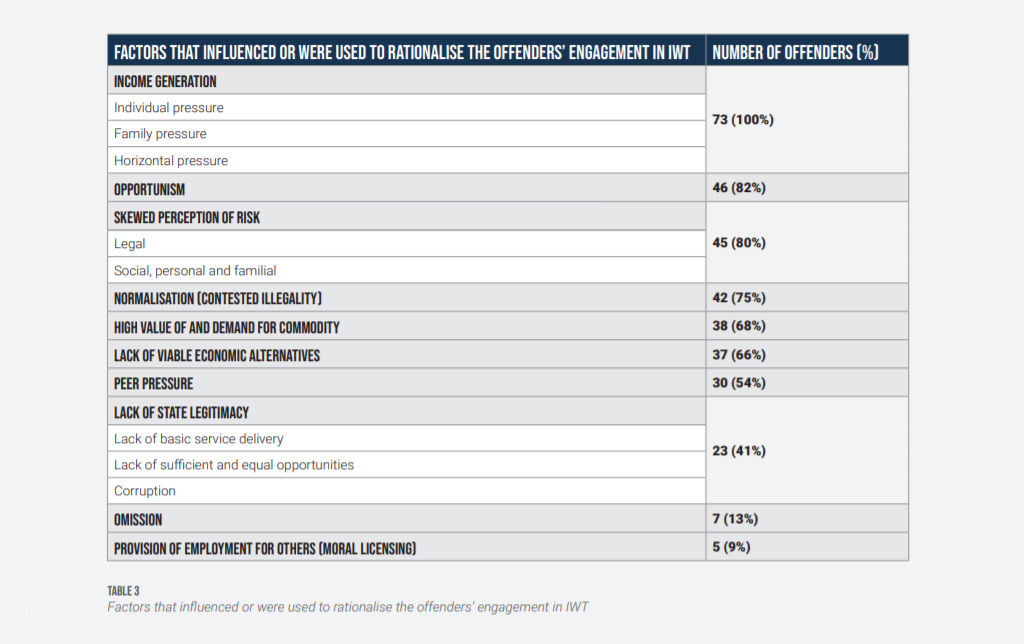

The report goes on to identify several factors that emerged as a common thread during the interviews with poachers.

- Income generation: Every single person interviewed pointed to income generation as a major influence in persuading them to participate in the illegal wildlife trade. For 70% of interviewees, this pressure related to providing for their families, in terms of either the basics such as food and schooling or more expensive hobbies or interests. Worryingly, the authors of the report note a trend to view “successful” individuals in communities as those who have accumulated wealth through involvement in poaching activities.

- Opportunism: 80% of the offenders point to opportunity was a factor, usually through meeting another person actively involved in illegal wildlife trade.

- Skewed perception of risk: While most of the interviewees were aware of the illegality of their actions, less than half of the interviewed individuals were aware of the seriousness or severity of the legal consequences, especially given that many members of the community were observed to be participating without consequences.

- Normalisation (contested illegality): 75% of the offenders suggested that using natural resources was a normal and acceptable way to earn a living – as legitimate as fishing or harvesting plants. There were no social deterrents at play and no concerns related to retaliation or ostracisation from their communities, or even a risk of being reported by those community members.

- High value of and demand for the commodity: Nearly 70% of the offenders referred to the high values of, and demand for, wildlife commodities and the fact that illegal wildlife trade was far more lucrative than other legitimate ways of earning money.

- Lack of viable economic alternatives: 65% of the offenders pointed to a lack of alternative ways to improve their financial and social circumstances. Most of the interviewees from Mozambique and Zimbabwe came to South Africa to search for employment opportunities, but the official unemployment rate in South Africa is 29.1%. This is predicted to increase due to the economic fall-out from the pandemic.

- Peer pressure: 44% of the interviewees indicated that they were influenced by peer pressure, almost invariably by family or close friends.

- Lack of state legitimacy: 40% of the offenders made some reference to dissatisfaction with legal authorities, whether related to a lack of basic service delivery, lack of sufficient job opportunities, wasteful expenditure, or corruption. There was particular frustration with corruption linked to the illegal wildlife supply chain.

- Omission: This category relates largely to those offenders that played a role in the supply chain, rather than active poaching. These interviewees perceive their activities to be distanced from the illegal wildlife trade.

- Provision of employment for others: A small proportion of interviewees employed individuals involved in illegal wildlife trade and claimed that they were responsible for putting food on the table for their “employees’” families.

These factors can be roughly divided into societal, community, and individual motivating factors. Naturally, any individual could be influenced by any combination of particular factors. Therefore, the TRAFFIC report suggests that a combination of collective strategies would be needed to increase compliance and prevent engagement in the trade.

Recommendations

The authors of the TRAFFIC report put forward several recommendations based on the outcomes of the interviews with poachers and the larger socio-economic context in South Africa.

The first is that concerted effort should be placed on investigating, arresting and prosecuting individuals that occupy the higher levels of illegal wildlife trade, rather than simply arresting and prosecuting poachers and drivers. The aspects and strategies outlined by the National Integrated Strategy to Combat Wildlife Trafficking need to be approved and implemented by the South African government as a matter of urgency.

The second recommendation is that the provision of public services such as health care, quality education, employment opportunity, food security and infrastructure are provided to those communities most at risk of being exploited by criminal wildlife trade syndicates.

The third recommendation involves local community-based interventions and initiatives (such as the Black Mambas Anti-Poaching Unit), which may include increasing incentives for wildlife stewardship; supporting livelihoods unrelated to wildlife; decreasing the costs associated with human-wildlife conflict; increase the costs of participating in the illegal; or education and awareness-raising.

The final recommendation is for the development of social intervention strategies that emphasise personal and familial consequences (rather than legal ones) and equip individuals with knowledge and tools necessary to resist peer pressure. This could potentially involve the sharing of previously unreported personal consequences experienced by offenders.

Conclusion

While active measures to safeguard South Africa’s precious wildlife resources are essential, the incarceration of ground-level participants such as poachers will have little impact if societal factors continue to motivate their replacements. Addressing some of the economic and social drivers is a significant aspect of the battle against illicit wildlife trade, and this is only possible with a holistic understanding of these drivers. As such, TRAFFIC’s report has wide-reaching ramifications that extend beyond its South African context into the wider world of illegal wildlife trade.![]()

The full report can be accessed here: “The People Beyond the Poaching: Interviews with Convicted Offenders in South Africa”, TRAFFIC (2020)

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()