Everything is still and quiet as the sun pounds the floodplain of the Zambezi Valley. It is late afternoon, but the intensity of the heat has not abated. In front of me are a group of animals lying in a heap. Occasionally a big round ear will twitch, or a head might lazily rise, only to flop back down in exhaustion from the effort.

It is Blacktip and her pack of 14 painted wolves and nine puppies sleeping in the dense shade of a Trichilia tree. I am sitting 20 metres in front of them, my long lens and camera resting on its tripod in anticipation.

Excitement is building within me. From years of observation, I know what is about to happen but, to the casual eye, there is nothing to betray the eruption that will soon take place. Without warning the sleeping wolves explode and begin a ritual of unbounded joy and energy. Every wolf is on its feet as they squeak and skip, run and race, bite and barge, nudge and nibble, duck and dive, leap and lick and sniff and snort… just for the pleasure of being with each other.

This is their greeting ceremony. It is like watching long-separated families meet at an airport, despite them having lain on top of each other all day.

For the last six years, I have been following and photographing three packs of painted wolves on foot, in Mana Pools National Park in Zimbabwe. This infectious joy of the pack is one reason why I have become obsessed with these creatures. Here in Mana Pools, the painted wolves are incredibly lucky. They live far from the ravages of man, living as so many packs have done before them, over hundreds of thousands of years.

Yet most painted wolves are far from this fortunate. For the species, the last century has been devastating. Their population has dropped from 500,000 to an estimated 6,600 today, confined to roam across just a few remote corners of the African continent.

What has caused this demise? Like all African wildlife, they have lost much of their rangelands from expanding human populations. But the painted wolves have faced a far greater assault. Considered vermin by European settlers anxious to recreate their European farming systems, the painted wolf’s threat to livestock was highly exaggerated by ignorant farmers and a systematic programme aimed at their annihilation was carried out through much of Africa.

Colonial administrations offered generous bounties for each painted wolf’s death, and visitors were even allowed to shoot them on sight in many of Africa’s protected parks. In Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), they were considered a ‘problem animal’ right up until 1977. In 1975 alone, 3,404 painted wolves were destroyed in vermin control operations.

Even today, I hear old farmers talk about this animal with such hatred, and I have slowly come to recognise that their ignorance is totally impenetrable.

An Incredible Creature

But for those that really know them, this image of the painted wolf as a wanton killer could not be further from the truth. They are fascinating animals, and each wolf is an individual, most of whom I have got to know well.

They live in a matriarchal society. Only the alpha female will breed with a single alpha male. The rest of the pack will take on a different role – a doting aunt or uncle, a hunt leader, a look-out sentry and even the local doctor that will lick the wounds of any hurt family member.

Each is an individual character, and I am convinced to this day that one of my favourite wolves, Pip, was the clown whose job it was to entertain the children. It is at the den that you get the sense of the cohesion of the pack. Although there is usually only one mother, every member of the pack plays a critical role in their nurturing and development. The adults hunt twice a day and return to regurgitate food for the pups and the adults that remained behind.

An Exceptional Hunter

Their skill as a hunter is well-known and painted wolves have earned themselves a reputation as Africa’s most efficient predator – some say that 80% of their hunts result in a kill.

In my experience, that number seems a little high, but not by much. While many individual chases may be unsuccessful, it is a rare day when the pack goes hungry. To watch them hunt is exhilarating. Their speed, stamina and agility combine to make a kill far more spectacular than any lion or leopard hunt. From what I have seen, the notion that the pack uses telepathy to communicate during the hunt does not stand up. I have stood in the centre of a hunt many times with wolves and impala rushing past me as I desperately try to photograph. It is more like opportunistic mayhem – every wolf for itself.

Once they have made a kill, any sense of individualism evaporates. To the casual observer watching a pack of painted wolves devour its prey, the frenzy seems savage as they rip the carcass apart. They need to eat fast as they are continually threatened by hyenas that attempt to steal their food, and frenetic battles between these two species are common with the little puppies often a casualty. Closer observation of the feeding frenzy reveals their sharing attitude. They always let the pups eat first. Then any wolf that is wounded, sick or elderly will be allowed to take their fill. The alpha female will often be the last to feed, once her pack is comfortably replete.

This is in sharp contrast to lions, where the big male hogs the kill and the rest of the pride must wait patiently until he is finished. And the little cubs only get to eat last. Rather than aggression, the dogs compete with submission, making for a far more harmonious, generous and kind existence. I am convinced this is because they are led by a female who nurtures rather than dominates.

Females Rule

Indeed, the alpha female is the core of the pack. She will lead her pack from its formation until she dies. She is the leader, general, decision-maker and caring mother. Once she dies, the pack splits, with the males and females heading in different directions to form new packs.

Tait of the Vundu pack was my favourite alpha female. She lived for over ten years and had eight litters, so her genes run through most of the dogs in the Zambezi Valley and probably beyond. Being with her, you could sense her strength of character. I remember when she was faced with an onslaught of 11 hyena against her 14 wolves. She seemed to stand back like a general and direct the defence, ensuring her pups remained safe. But she was no coward. When things got particularly hectic, she would be there in the mix.

As head of the pack, the alpha female presides over the pack’s generally harmonious family life. You get the sense that they really do care for one another with a deep bond of love. Or at least that is the best description I can provide, observing them from my very human viewpoint. Watching them at playtime is perhaps the greatest joy, especially around water. As the sun begins to set and temperatures cool, the pups run around ambushing each other and baiting the dozing adults. The grown-ups often can’t resist the fun and games, joining in with more vigour than the pups.

For the painted wolves, life in Mana Pools is how it should be. However, it is not all plain sailing. Hyena attacks are frequent, and the lions are a continual threat and are responsible for the deaths of many wolves. But in the remote Zambezi Valley, they are protected from their species greatest scourge… mankind.

A Threatened Existence

In the west of Zimbabwe, Hwange National Park is surrounded by communal lands where the painted wolves are in daily contact with man. Here they are subjected daily to road kills, disease, snaring, as well as intolerant farmers.

Rabies and distemper often spread from domestic dogs, annihilating entire packs. Villagers lay snares to catch antelope to feed their families or pay for education. Painted wolves, while not the target, are all too often caught in these snares with fatal consequences.

While it is easy to criticise the villagers for laying snares, I would challenge anyone to say they would not do the same if their family was starving or their children unable to attend school. This is where organisations like Painted Dog Conservation (PDC), run by Peter Blinston, play a vital role. Not only do they carry out critical research and run a small army of anti-poachers to collect snares and apprehend criminals, but they also work hand-in-hand with these communities.

They build boreholes, plant vegetable gardens, vaccinate domestic dogs and have built a string of medical clinics with HIV/AIDS and maternity facilities. These things really matter to the communities, and the message is simple.

“Without the painted wolves, PDC will not be here and neither will the benefits we bring. It is the wolves that are bringing these things to you.”

This message seems to be working, and the communities have even set up their own voluntary anti-poaching team, an initiative entirely of their own making.

This approach certainly has an impact in the short term, but long-term, education is the key. PDC has set up a Bush Camp which brings in over 1,000 children a year for a four-day course on the painted wolves, science and conservation. The camp is designed to change hearts and minds, in an environment which for the children is like going to Disneyland. Attitudes are changing, and this is what is necessary if the painted wolves are to have a chance.

Beyond the villages and communities that must live with these predators on their doorstep, the painted wolves face a more significant problem. That is that so few people know that they exist.

In the conservation world, the elephant, rhino and lion continue to grab all the attention, while the painted wolf is not only ignored but unknown. Of course, these other animals are important – it is not a competition. But the painted wolf needs to be up there on the top table of conservation, especially given that so few remain.

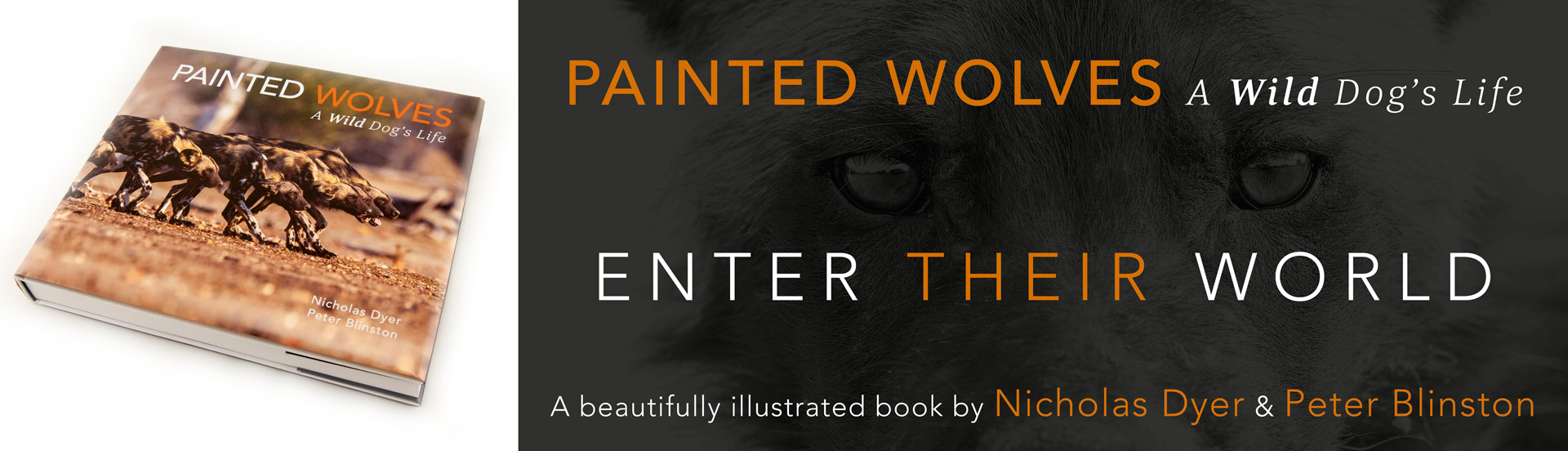

To address this, Peter and I, together with leading conservationist Diane Skinner, have set up the Painted Wolf Foundation. Its objective is to increase the awareness of the painted wolf and raise money for organisations working for their conservation. Peter and I have also produced a book called Painted Wolves: A Wild Dog’s Life, which describes in detail the lives of these incredible creatures and what is being done to conserve them. It has been six years in the making and features the same packs in the BBC’s incredible film Painted Wolves: A Wild Dog Dynasty, narrated by Sir David Attenborough.

Turning the Tide

In the race to extinction, it is the painted wolves that are winning. It is a race they never wanted to enter. Few know they exist and even less care. As a species that has mistreated them, it seems to me that if we humans want to describe ourselves as more enlightened, we need to do something to tilt the balance back in their favour.

This is my passion. This is why we have the Painted Wolf Foundation. What we need is for more people to join us and become “Part of the Pack”.![]()

ABOUT THE PAINTED WOLF FOUNDATION

The Painted Wolf Foundation was set up by Nicholas Dyer, Peter Blinston and leading conservationist Diane Skinner. The Painted Wolf Foundation aims to raise awareness about this much threatened and ignored species and support organisations that conserve painted wolves in the field.

The Painted Wolf Foundation has launched a significant campaign to raise global awareness about the species and its plight, working with many partners around the world and within Africa. For six years, wildlife photographer and author Nicholas Dyer has been tracking and photographing the painted wolves on foot in the Zambezi Valley. For twenty years, conservationist Peter Blinston has been doing all he can to save them from extinction.

What the foundation does:

• Raises awareness about the painted wolf worldwide

• Increases the support base for the painted wolf

• Elevates the profile of the organisations working to conserve painted wolves in the field

• Raises funds to support field-based conservation of the painted wolf

• Encourages sharing of best practices

• Supports painted wolf campaigns worldwide

The foundation does this by combining expert conservation knowledge with skills in communication and social media.

THE BOOK

PAINTED WOLVES: A Wild Dog’s Life

The painted wolf is a unique and remarkable creature. On the one hand, it is Africa’s most successful predator, yet on the other, it is an incredibly social animal, caring deeply for its family’s wellbeing in a tightly knit pack.

Yet for the last 100 years, the painted wolf has endured an outrageous onslaught, which has seen their numbers decrease from 500,000 a century ago to only 6,500 today. This 99% reduction in their population has put the wolf’s survival on a knife-edge.

Painted Wolves: A Wild Dog’s Life is their story. It is told with insight and passion from two people who know them well, each with their own unique perspective on this endearing animal.

For six years Nicholas Dyer has been tracking and photographing painted wolves on foot in the Zambezi Valley. For twenty years, Peter Blinston has been doing all he can to save the painted wolf from extinction through his organisation Painted Dog Conservation.

In this book, they have come together to tell you what they know and love about this incredible creature, sharing their in-depth knowledge and unique experiences.

The book is illustrated with more than 220 stunning images. Each photograph tells a story and brings alive the captivating and mysterious world of the painted wolves and the lives of those around them. All profits from the book will go to the Painted Wolf Foundation.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR, Nicholas Dyer

Nick grew up in Kenya and always had a passion for photography. After careers in finance and marketing, stuck behind a desk in London, he took the decision to return to Africa and turn his life around to dedicate it to photography, writing and wildlife conservation. In 2013, he discovered the painted wolves of Mana Pools National Park and fell in love with them. Nick has spent much of the last six years living in a tent while following and photographing three packs on foot.

He is the co-author of Painted Wolves: A Wild Dog’s Life, a founding trustee of the Painted Wolf Foundation and a finalist in the prestigious 2018 Wildlife Photographer of the Year Competition with his picture – ‘Ahead of the Game’. See more of his photography at www.nicholasdyer.com, and follow him on his Facebook and Instagram page.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()