OPINION POST by Dr Chris Brown and Gail C. Potgieter, on behalf of the Namibian Chamber of Environment’s 64 member conservation organisations

Conservation organisations in Namibia support the recent decision by the US Fish and Wildlife Service to grant an import permit for a black rhino trophy from our country. Responses to this decision from some US organisations and the public, however, reveal that there is still strong opposition to hunting. We believe that this opposition stems from a lack of knowledge and understanding of how hunting fits into the Namibian conservation model. Please allow us to explain.

Against the backdrop of a global extinction crisis and booming illegal wildlife trade that fuels poaching throughout Africa, Namibia is an exceptional conservation success story. We are amongst a handful of countries in the world that have enabled wild animals like rhinos to increase in their natural habitat. After nearly losing all our precious free-ranging black rhinos during the dark apartheid era, we are proud of the fact that today, Namibia hosts close to 2,000 black rhinos. These account for 33% of the entire black rhino species and 85% of the south-western subspecies.

By global standards, Namibia is not a wealthy country. Many Namibians struggle to meet their daily needs in the harsh desert environment, a situation that may worsen with climate change. Our government is faced with numerous competing socio-economic demands for its scarce resources – education, health and drought relief, to name a few. Dedicating funds to protect black rhinos from poachers while simultaneously meeting manifold development challenges is tough, to say the least.

The Namibian solution to this daunting task is to use the full value of our rhinos and other wildlife to fund conservation and sustainable development. In a welcome departure from the exclusionary policies of the past, our post-apartheid independent government has included local people as key partners and beneficiaries of wildlife conservation.

The direct benefits from wildlife include income and increased food security from photographic and hunting tourism, which operate within the same areas in Namibia without negatively affecting each other. A recent study in Namibian communal areas found that while the two industries are complementary, photographic tourism could not fully replace hunting if the latter were banned. These tourism sectors together generate significant income from Namibia’s wildlife, which funds conservation.

Notwithstanding the significant heritage and ecological value of black rhinos, they cannot be effectively protected from poachers without substantial funds. The US$400,000 paid to Game Products Trust Fund (GPTF) for the recent black rhino hunt provided a welcome boost to Namibian conservation. The GPTF links income from government wildlife sales and trophy fees directly to on-the-ground conservation.

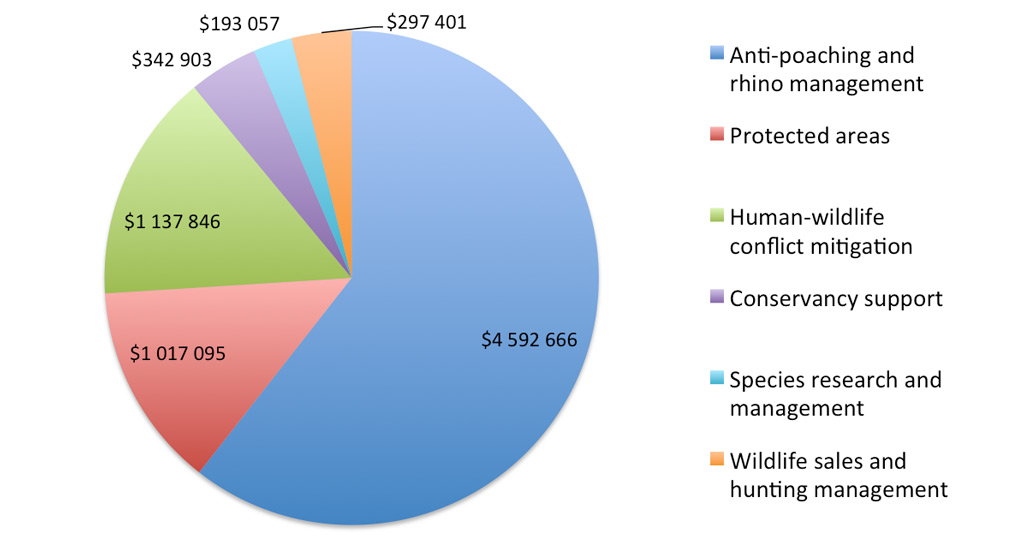

Between 2012-2018, GPTF spent over US$7.5 million on conservation projects; 61% of this expenditure (about US$4.6 million) was dedicated to anti-poaching and rhino population management (Figure 1). US$2.3 million of this budget provides direct support for anti-poaching teams.

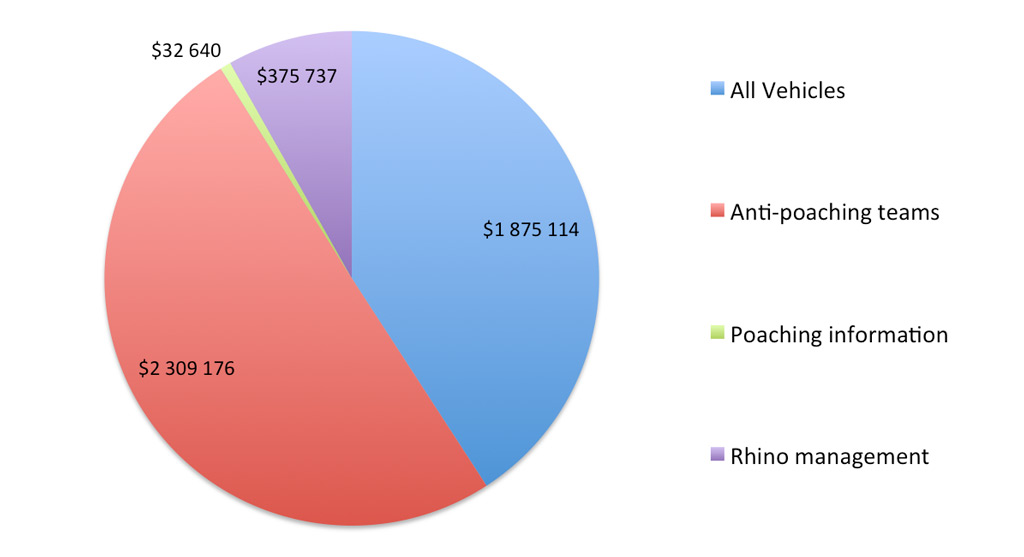

The remaining funds are used for anti-poaching vehicles (including helicopters and boats), managing and monitoring rhino populations, and rewarding informants who provide tip-offs leading to poacher arrests (Figure 2).

Namibia’s substantial rhino populations have unfortunately attracted organised poaching syndicates. To counteract increased poaching in 2014 and 2015, the government and their partners mobilised funding from GPTF and other sources to strengthen and coordinate their anti-poaching efforts. Consequently, black rhino poaching declined by 33% during the last three years. Etosha National Park, which hosts the largest rhino population in the country, reported fewer than 30 incidents in 2018, down from a high of 80 in 2015. Even more impressive, communal conservancies that host free-ranging black rhinos have recorded zero poaching incidents during the last two years!

Besides the economic benefit of this hunt, removing old bulls from the population also increases the rhino population growth rate. Particularly in small black rhino populations, older bulls can become a problem. They prevent young bulls from breeding and may even kill them in territorial fights. The females in their territories are likely to be their daughters, so keeping these old bulls in the population may jeopardise its genetic integrity. Black rhinos are managed by the Ministry of Environment and Tourism, which oversees a highly successful black rhino custodianship programme on freehold and communal land. Removing older bulls from these smaller populations is thus part of their broader black rhino population management plan.

Considering the successful Namibian conservation model and our collective colossal efforts to reduce poaching, the recent public comments suggesting that money from the black rhino hunt would be misappropriated are especially offensive. The “animals first” message promoted by animal rights and welfare organisations has alienated rural communities throughout Africa as it disregards their rights and ignores their needs. For wildlife, the result is widespread habitat loss and animal extermination. While certain ideologues want to pressure Namibia into accepting this lose-lose scenario, we would rather support the proven, home-grown strategy that reaps rewards for people and wildlife. We invite you to visit Namibia and see our success for yourselves.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()