Opinion post by Simon Espley – CEO Africa Geographic

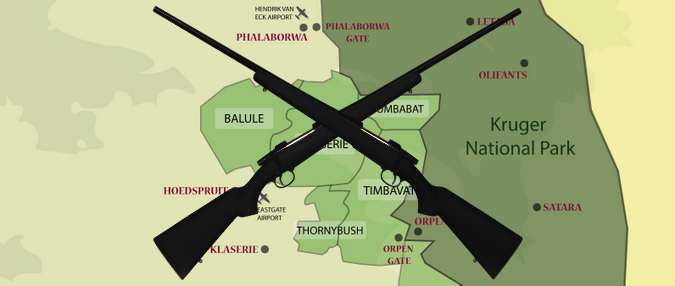

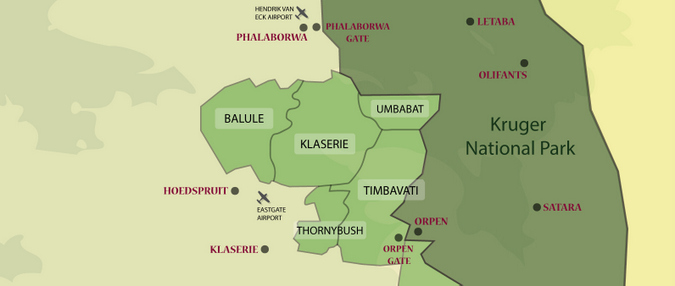

NOTE: This opinion post relates exclusively to trophy hunting on land that shares an unfenced border with the Kruger National Park in South Africa. It does not refer to any other form or location of hunting, although I do refer to other areas in the opening paragraphs. Hunting is a complex and emotional topic, and my focus here is specific.

It is no secret that the trophy hunting industry staggers from one unsavoury incident to the next, be it baiting and shooting of pride male lions, illegal collared elephant hunting or the surgical removal of the remaining large-gene animals. Cecil the Lion was just one example that hit the viral stratosphere, but this kind of behaviour goes on all over Africa, often unreported or not picked up by mainstream media, and it swamps the good that does result from some hunting operations.

Recently, respected filmmaker and conservationist Dereck Joubert shared some of his experiences with trophy hunters that massacred their way through Botswana in the old days. His recollections make for harrowing reading. I have heard similar accounts from multiple people, including former professional hunters.

In the latest trophy hunting-related disaster, South Africa’s Parliament has attacked Kruger’s magnificent and visionary 10-year plan by calling for the nullifying of the recently signed agreement between Kruger and neighbouring private and community reserves. Who knows what political manoeuvrings are behind this, but it is notable that trophy hunting and a perceived lack of local community benefits were at the root of the statement from Parliament.

The trophy hunting industry could play such a powerful role in African conservation (there are some examples where this does happen), but in practice it simply refuses to adapt to modern-day conservation realities and rid itself of unsustainable take-offs, corruption and the bad apples that taint the entire industry. The main focus and revenue drivers are the targeting of big gene elephants, lions, leopards, buffalos etc and these have become increasingly scarce in the wild, resulting in drastic (sometimes illegal or contrary to agreed protocol) antics to secure the desired trophies. Fenced private game farms appear to be better managed as trophy hunting businesses, with arguably more sustainable practices. For open ecosystems though, this is a classic case of the Tragedy of the Commons. It appears that this rudderless industry will not change – it is what it is, and it simply does not operate in a manner that is conducive to sustainability in large ecosystems with multiple landowners and land-use models. Such as the Greater Kruger.

BUT BACK TO MY HEADLINE…

Last year I wrote to the good people of the Associated Private Nature Reserves (APNR), a collective of private reserves that forms part of the Greater Kruger. I know some of them personally – good people who want the best for conservation. I cautioned them that their fund-raising model needs to change. Trophy hunting constitutes a sizeable chunk of the revenue pie that is applied to manage the reserve and keep wildlife safe from poachers. They acknowledged my letter politely, but I got the sense that the day-to-day reality of the issues that they face prevent them from taking too seriously warnings of the coming storm.

My warning was not based on ignorance as to the amount of revenue raised by trophy hunting and the significantly lower eco-footprint per Dollar raised of trophy hunting versus that of photographic tourism. I am well aware of these realities.

Rather, my warning was that the rolling snowball of public rage at killing animals (particularly large-gene individuals) for fun and ego is growing in size and momentum every day, and the consequences will only increase. And social media and other technologies are empowering millions of new-age activists to pursue and persecute trophy hunters and others in the industry. Ask that dentist Walter Palmer if he would do it again.

I stressed to APNR management that their personal faith in the trophy hunting industry and their granular understanding of what it actually takes to manage, and keep safe from poachers, vast tracts of wildlands, are simply not deemed relevant in the court of public opinion. Unfortunately, what is relevant is that the emotional tidal wave will quite simply swamp all of that, and reduce the APNR to tatters if public opinion is ignored. We now live in a world where accumulated opinion becomes fact, emotion trumps knowledge, and experience on the ground has a low ranking. Those are the cards that we have been dealt with. Thank you, Facebook. I am not suggesting that APNR management surrender and let public opinion and the hordes of ’emotional keyboard warriors’ (favourite hunter term) manage the Greater Kruger. Heaven forbid! I am suggesting that they make wise decisions about aspects of their model that do not seem to have longevity, and where the risk of brand destruction is high.

My parting comment was that surely they had no choice but to stop trophy hunting as soon as possible and seek alternative revenue-raising strategies. I expressed faith that the significant combined intellectual and financial muscle amongst the landowners and lodge owners (often separate entities/people) would come up with a plan.

Timbavati, one of the APNR reserves, recently increased the conservation levy paid by visiting tourists, and now cover 55% of their operational budget from this revenue source (the rest comes primarily from trophy hunting). Based on simple maths explained to me recently, increasing that levy from the current R368 to about R750 per person per night would remove the need for any trophy hunting. This arithmetic is of course subject to assumptions, such as demand staying the same, but in broad strokes this number holds water.

The 19 commercial lodges in Timbavati charge on average R8,275 per person per night, so the suggested increased conservation levy would still pale by comparison. So there is one workable solution for one particular reserve.

Would travel agents and tourists agree to this increase? Time will tell. This model of increasing conservation levies paid by photographic tourists will not work in all of the reserves incorporated into the APNR, because some simply do not have not enough commercial lodges relative to land size and management costs. Those reserves have to find another model – perhaps including funding by the passionate and powerful anti-hunting lobby?

Two community-owned reserves in the Greater Kruger (but outside the APNR) only have trophy hunting as a revenue source. The larger of the community-owned reserves with open fences to the Kruger (the 42,000 hectare Letaba Ranch) is now buried in chaos, after the trophy hunting operators left after being accused of unsustainable offtakes, baiting animals from the Kruger and of channelling little or no benefit to the community landowners. That reserve is now in a nosedive, with increasing illegal mining on the property, and poaching. Remember that there are no fences between this reserve and our beloved Kruger.

If the current situation persists (trophy hunting of Kruger animals in neighbouring properties), the probable result of the rising public anger and politicisation by opportunists could see the APNR and others being forced to disband and fences going back up. In that case some of the landowners will revert to livestock and crop farming and intense trophy hunting. After all, they own the land and can utilise it as they choose. That would be a catastrophe, and the knock-on effects could be significant – Kruger’s big westward expansion plans could wilt and die, and the tourism industry in that area would collapse – taking with it many jobs and trickle-down benefits.

Remember that by far the best way to protect species such as elephants, lions and wild dogs going forward is to secure more land for them to roam and that the vital east-west migration patterns are at stake. Kruger’s 10-year management plan does just that. Kruger has to expand, and its laudable ten-year plan to do so depends on this model of incorporating other land under one conservation footprint. The Greater Kruger (and APNR) is a majorly important part of the 10-year plan and shining light on the conservation landscape. It is a thriving working model that requires ongoing evolution, and this discussion is part of that process of constant change. We have to get this right.

The trophy hunting industry seems, by virtue of its behaviour, not capable of playing a constructive role in the future conservation landscape on the western border of the Kruger National Park. Plus, the increasing public awareness and assertiveness will most likely eventually take down any attempt to involve that industry. Decision-makers can ignore these realities, or they can undertake the hard task of finding alternative conservation-funding models.

Keep the passion

Also read: Pro hunter responds to our CEO regarding hunting in Greater Kruger

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()