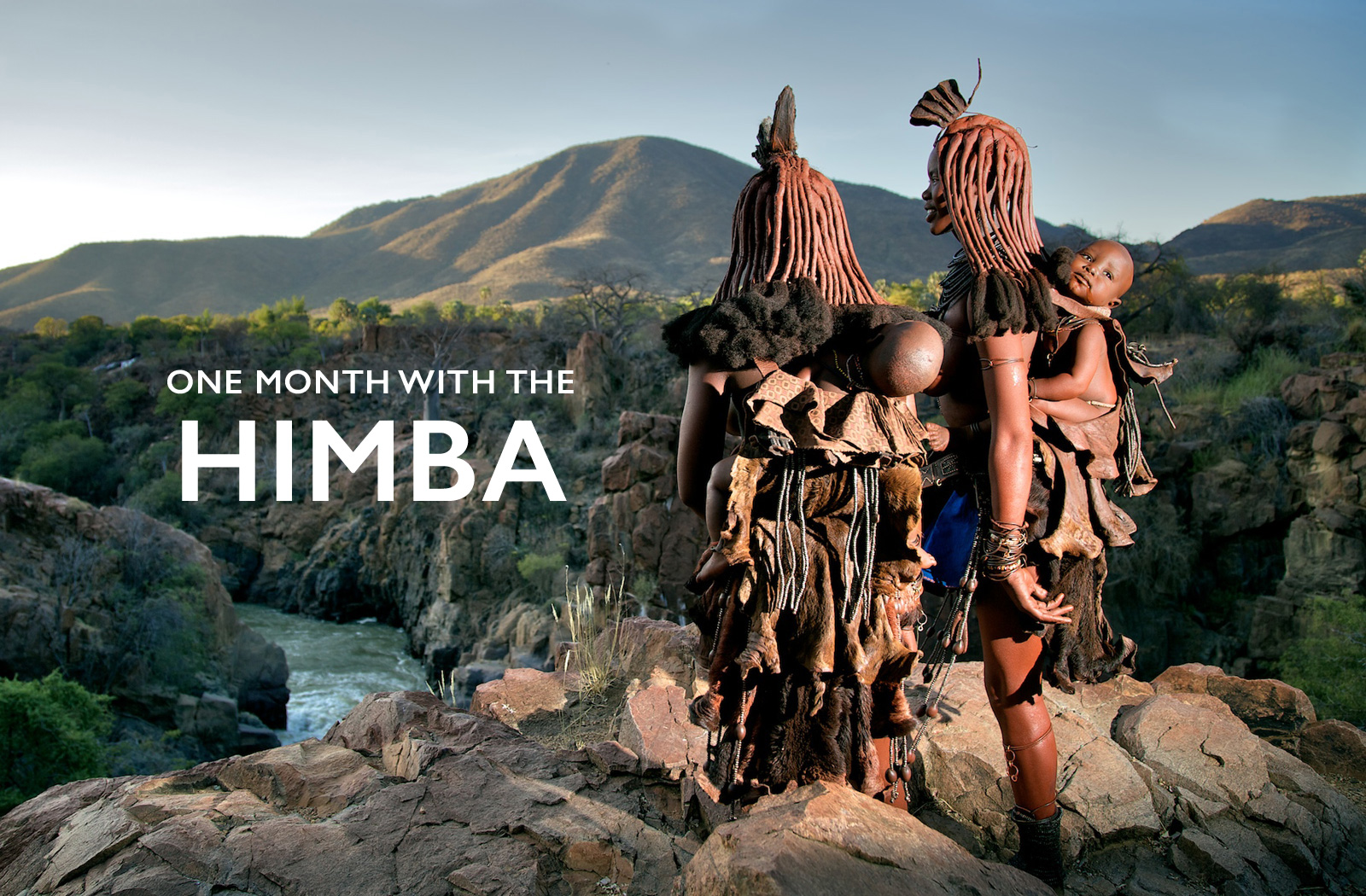

AN INTIMATE ACCOUNT OF NAMIBIA'S MOST ENIGMATIC TRIBE

I studied nature conservation in South Africa and then went away for 13 years, but the vast landscapes, extraordinary wildlife and ancient cultures drew me back. So, in 2014, I found my way to a Himba community in Namibia’s Kunene region.

After a 10-hour bus trip from Windhoek and another few hours in a car, I arrived at the regional capital Opuwo, a town of 15,000 people. I was stunned when I first saw a Himba woman. It was surreal to see a person wearing animal skins in a shopping mall. What followed was a month-long stay with the Himba along the Kunene River near Epupa Falls. This formed part of a long-term documentary project called “Wild Born” that focuses on tribal women worldwide.

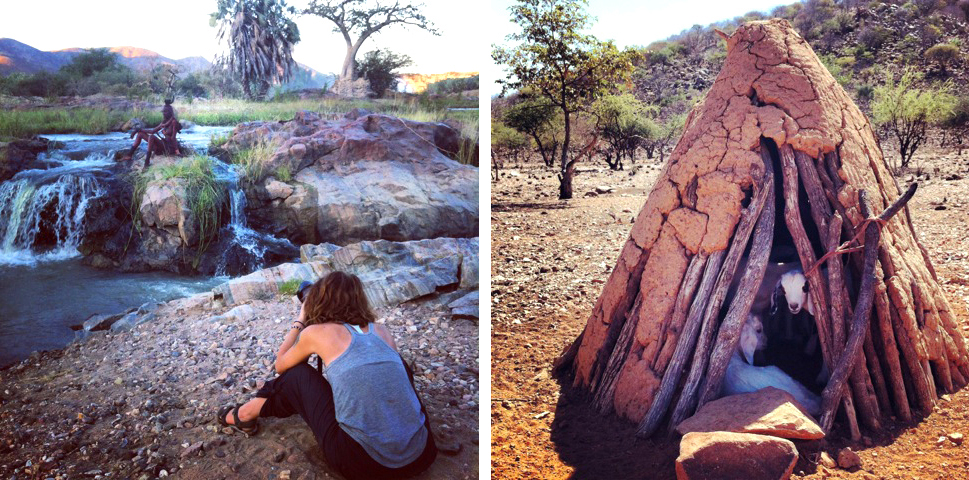

A pen prevents goats from escaping and protects them from predators.

The author and a group of Himba mothers walk with infants in traditional carriers.

Himba huts are constructed by plastering mud over a wooden framework.

©Alegra Ally

While with the Himba, I encountered a fascinating world that is rich and complex. The communities I stayed with were predominantly female. Some had just six members, others more than a hundred women sharing their lives. The Himba are polygamous, so traditionally, a woman would settle in her husband’s household, where she would live with his other wives and extended family.

Himba children are raised with the support of other women

The men are often away tending cattle at outposts, where they might have another wife or partner or may even go to towns to find work. As a result, many women stay permanently in their traditional villages, conducting their daily activities without men’s involvement. And many of them raise their children without fathers but with the support of other women. It was the resulting strong sense of womanhood on which I focused my documentary work.

Most Himba ceremonies and rituals are directed at ancestral spirits thought to have supernatural powers. One of the most significant is that of the holy fire, called Oruzo, which burns continually in each village and represents the link between the living and the ancestral spirits.

On reaching puberty, a girl leaves the village until she is initiated into womanhood

I witnessed several social rituals, including a girl’s initiation. On reaching puberty, she must leave the village until she has been ritually brought into her new social standing. Supported by the women in the group, she is taken to a special enclosure where she is spiritually protected during her first menstruation. She is given many gifts at this time, and ultimately, once she is presented to the spirits, her change in status is official, and a traditional leather crown is mounted upon her head as a symbol that she is marriageable.

Herbs and roots are ground with a stone to make a perfume to scent the woman’s body.

The author rests with a Himba child on the rocky bank of the Kunene River.

The same ochre and butterfat mixture that colours Himba skin is also rubbed into women’s hair.

©Alegra Ally

The Himba arrange their hair in very special ways. Girls have two primary braids that face forward, but when they reach adulthood, the braids are swept back and transformed into the familiar long, red plaits that are covered with Otjize, a mixture of butterfat and ochre. This is also regularly rubbed into the skin because the Himba seldom wash with water, which is scarce in this arid region. The mixture serves to protect and clean the skin and is an attractive adornment giving the Himba their distinctive ochre colour. Himba women and girls also like to perfume themselves in a morning ritual. They collect aromatic tree roots, which they mix with herbs, crushing them together using a hot stone, and then burning them to create heavily perfumed smoke. They sit close to the fire, covering themselves with a blanket to absorb the scent.

It is usual to find young boys in the villages but as they grow older, they build strong brotherhoods forming tight-knit groups that move around, stopping at villages for a few days and then moving on. It was common to see such groups in Opuwo and at Epupa Falls. Most of them are looking for jobs but, as I realised, there is little opportunity in the towns, so the boys spend their time walking around without any work.

The Himba often find themselves confused, not fitting into their village or town

The Himba find it hard to adjust to modern life and often find themselves confused and feeling “different” – not fitting into their village or town. But progress is inevitable and has both positive and negative effects. One of the most profoundly detrimental is the opening of bars and the selling of alcohol. Directly or indirectly, it affects almost everyone – from elders to young children.

During my time in the villages, several cars and safari trucks stopped by. The Himba women are sought after by photographers for their striking beauty and ochre body colour, and their warm and accepting character helps tourists feel welcome.

©Alegra Ally

Despite being exposed to tourism and development, the Himba remain predominantly traditional and seem to enjoy the attention. They benefit financially from tourism, as they sell souvenirs from small markets and sometimes accept money for photographs. But, while there is nothing wrong with photography, the tourists’ experience seldom goes deeper than that, and there is no understanding of the effects of progress on these fragile communities.

We can learn a lot from the Himba way of life, from the concept of communal living based on sharing, caring for each other, and living sustainably. As Westerners, we are so occupied with our sense of self, trying to achieve personal success and growth, that we forfeit quality time with family. I also believe that indigenous people like the Himba, who live closest to nature, are often our greatest allies in trying to protect it.

View Ally’s photo gallery Himba – Wild Born.

Contributor

ALEGRA ALLY is a Documentary photographer and a Fellow member of “The Explorers Club NYC”. She currently lives in Sydney, Australia, where she is completing her MA studies in Applied Anthropology. Ally is committed to working on issues relating to empowerment of women and girls, diminishing cultures and the environment. As part of her project ‘Wild Born’, Ally spent the last four years travelling to some of the most remote corners of the world where she lived with isolated tribes.

ALEGRA ALLY is a Documentary photographer and a Fellow member of “The Explorers Club NYC”. She currently lives in Sydney, Australia, where she is completing her MA studies in Applied Anthropology. Ally is committed to working on issues relating to empowerment of women and girls, diminishing cultures and the environment. As part of her project ‘Wild Born’, Ally spent the last four years travelling to some of the most remote corners of the world where she lived with isolated tribes.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()