Walk on the wild side

![]()

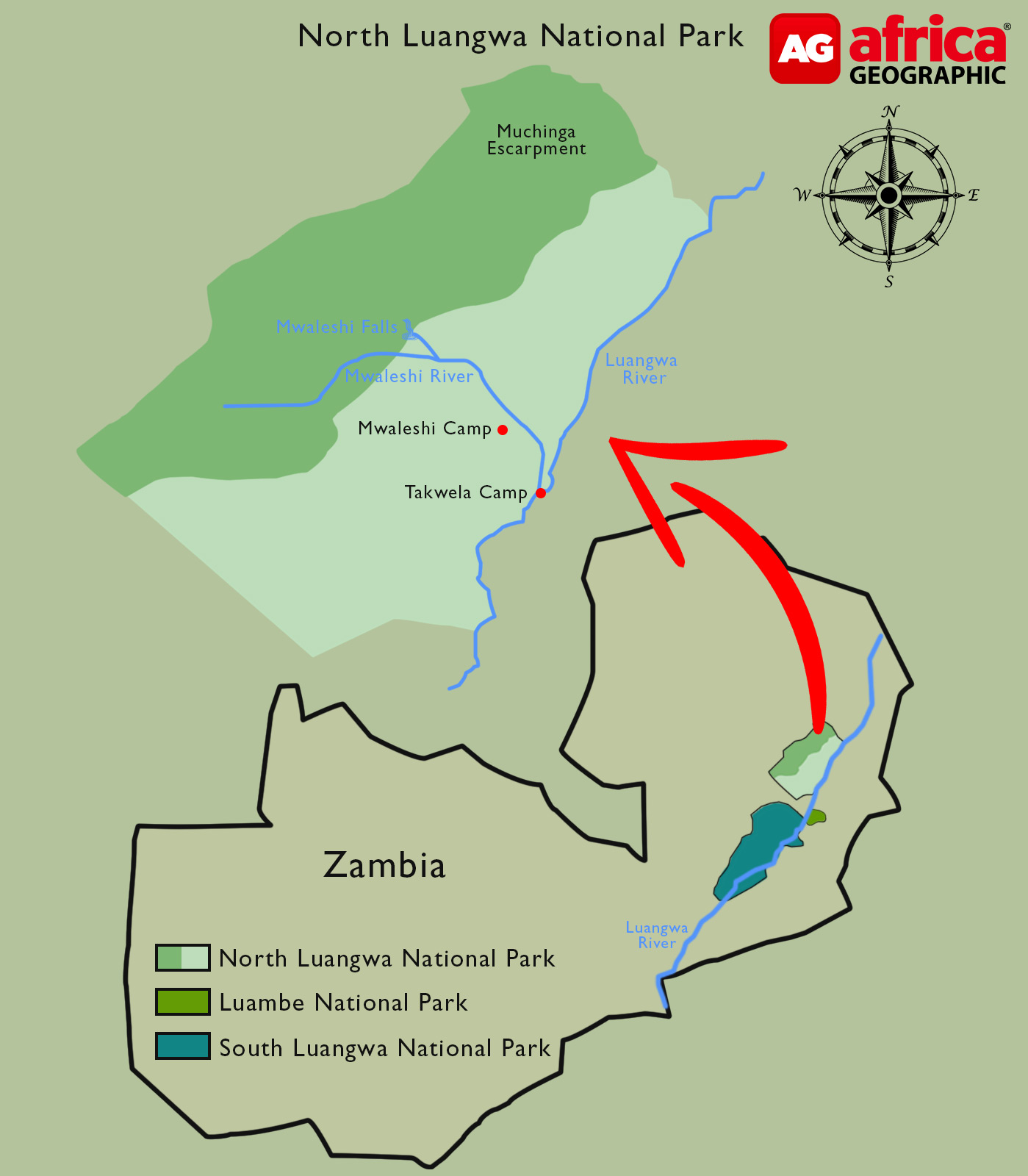

Africa’s Great Rift Valley extends southwards into north-eastern Zambia. Here, the Luangwa River, a tributary of the Zambezi, has carved out a unique and beautiful landscape. This remote area is home to Zambia’s only black rhinos and has one of the highest lion densities in the region. North Luangwa is remote and wild, accessible only by air or if equipped with excellent 4×4 driving skills, so we had come to explore this fantastic place on foot. With few roads and even fewer people, you are unlikely to see anyone else for the duration of your safari.

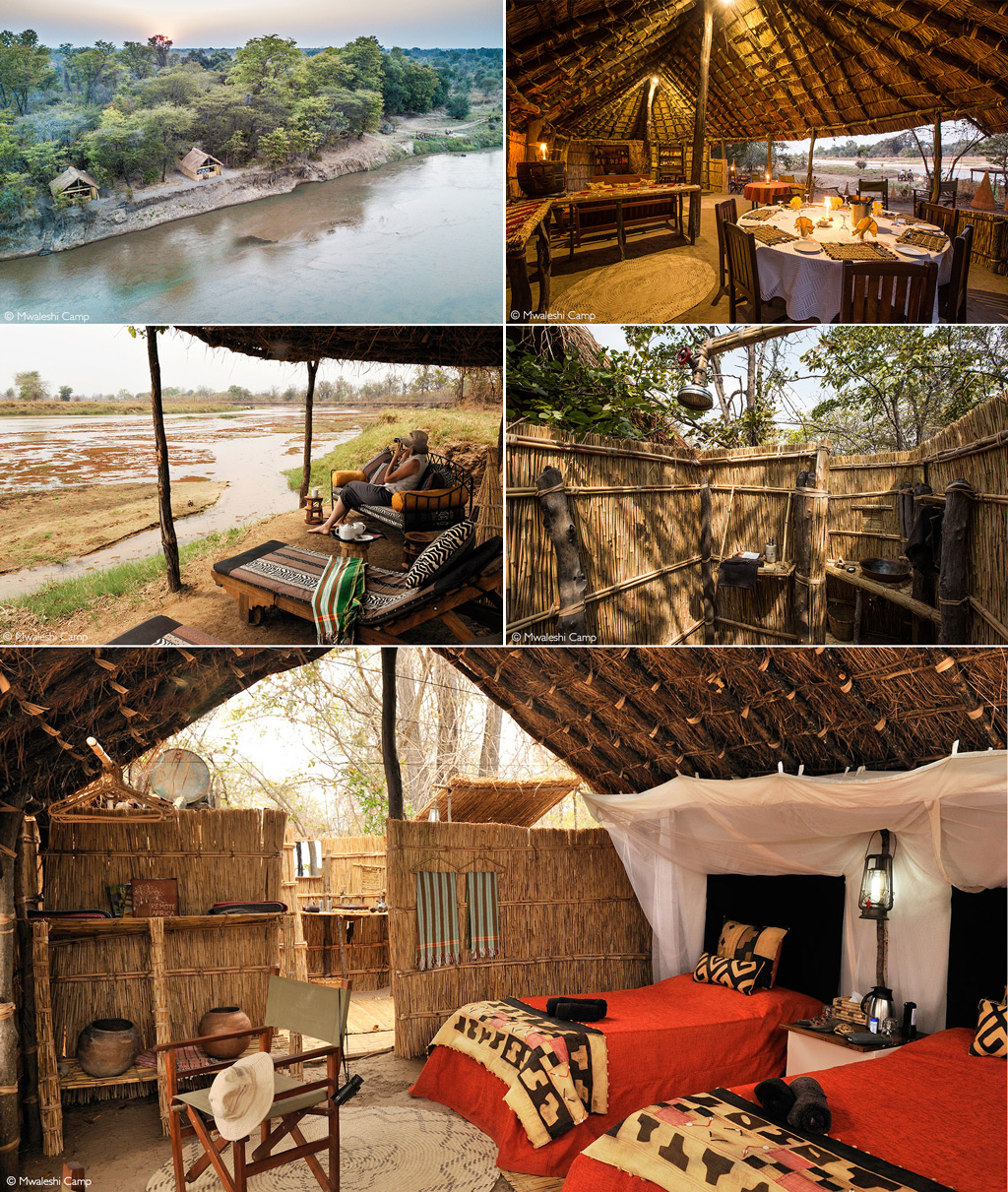

On our route there, we stopped overnight at Chikolongo campsite on the outskirts of the park, high on the dramatic Muchinga escarpment which accounts for 24 % of North Luangwa NP – just one of its diverse range of habitats. The next day we headed down the escarpment and into the park, driving for a couple of hours before arriving on the bank opposite the camp across the wide and sandy Mwaleshi River. Having had some vehicle issues, we were rather reluctant to drive across, and after a little arm waving and exaggerated miming to the team on the opposite bank, a couple of camp staff were dispatched on foot to assist us with our luggage. We all waded across the shallow water together, arriving at Mwaleshi Camp in time for lunch.

Walking out from camp that afternoon, we were given safety instructions: “stay behind the guide, single file, no loud noises, pay attention, and do NOT wander off”. We walked through long grass, across rivers, ducked under branches and occasionally stopped to untangle ourselves from ‘wait-a-bit’ thorn bushes. The bushveld is very different when experienced on foot – you become aware of every rustle and crackle in the undergrowth, the snap of every twig underfoot.

Our first afternoon walk lasted three hours. A magnificent martial eagle soared overhead, and lilac-breasted rollers displayed vibrant colours as they swooped through the air. Rattling cisticolas shouted warning calls and grey go-away birds, with their distinctive cries, were everywhere. We watched the insect-catching antics of bee-eaters, the ungainly flight patterns of hornbills and had an up-close look at the various nest styles of some of the 12 different weaver species found in North Luangwa. The air was heavy with the heady aroma of Natal mahogany blossoms.

Cresting a rise as we approached the river, we found three lions lying in the sand, about 30 metres ahead. We sat on the ground and watched them sleep. A persistent honeyguide called repeatedly, trying to get our attention and almost revealing our location to the lions, who from time to time raised their heads to see what the commotion was about. As we sat, our guide Brent explained that the honeyguides hope to lead us to a beehive, in the hope that we extract honey and leave some for them. He also explained that honeyguides are brood parasites, laying their eggs in the nests of another bird species, very often bee-eaters. They physically eject the host’s chicks from the nest or puncture the host’s eggs with the needle-sharp hooks on their beaks, and any of the host’s young that do hatch are stabbed to death by the honeyguide chicks, to eliminate competition. Incredibly, honeyguides have also developed the ability to produce eggs and young that mimic the egg size and gape of their hosts so that the interlopers can pass undetected in their foster homes. It also seems that their ability to produce eggs of similar size to those of their varied host species is not just to prevent choosy hosts from ejecting mismatched eggs, but also to fool other honeyguides, who would otherwise destroy the eggs because of fierce competition for suitable host nests.

Leaving the lions and the honeyguides, we headed back to camp. Sunset turned the river orange and scarlet as we walked along the bank. The smell of potato bush hung in the air, as did the trademark popcorn smell of a genet’s scent markings. Back in camp that night we ate dinner by lantern light, overlooking the darkened river. Hyena calls filled the night sky, lions roared on all sides, and a young elephant across the water trumpeted in alarm.

A typical day’s walking safari in North Luangwa starts at about 5 am. After coffee and breakfast around the campfire on the riverbank, we set off for what would be a five-hour walk. Taking off our shoes, we crossed the river. Almost immediately we saw the spoor of the previous day’s lions, but they proved elusive, always seeming a few steps ahead of us. The sun rose and the tsetse flies became a little more blood-thirsty. We skirted the mopane scrubland edge and watched the tantalising lion footprints heading deeper into the forest. We continued, walking through sand, over river pebbles, past woodland and across grassland. The occasional nocturnal creature rustled in the undergrowth as they made their way home, while birds and other daytime creatures started to wake up.

We were pursued by a succession of honeyguides, each one seemingly keener than the one before to lead us to the ‘honey prize’. A couple of Cookson’s wildebeest (one of the valley’s endemic subspecies) crossed our path, followed by a lone bull elephant, walking along the top of the riverbank. He found a tree laden with fruit and paused for a leisurely meal. Along our walk, ilala palms marked the ancient trails taken by elephants, who had eaten the ginger-chocolate tasting palm fruit and deposited the seeds in their gigantic droppings as they walked. As the day grew warmer, we moved into a grove of bushes on the edge of an almost-dry pan. There was a trickle of water remaining, just damp enough to attract elephants, baboons and warthogs, but not quite deep enough to conceal a small crocodile.

Lunch and a ‘swim’ in the shin-deep water of the Mwaleshi River right below our room, followed by a siesta, had us refreshed and ready to head out again on foot in the afternoon. Brent gave us a lesson in animal psychology. Explaining to us that if we ‘walked with purpose’ in a straight line, focussed on a destination, we appeared to other animals as a potential threat – like a predator. However, when we stopped to look at plants or birds or footprints, giving the appearance of milling about aimlessly, then our behaviour was less threatening, allowing us to get a lot closer to our quarry. We also learnt that among the larger general wildlife species, there are at least two distinct types of breeding/territorial behaviour. There are those like the wildebeest, where a lone male will guard what he feels to be prime real estate, and which he hopes will attract a bevvy of eligible females into his domain. Then there are those like the zebra, where a male will maintain a harem of females and exert his energy rounding up his females and fending off any rival males.

The rest of our afternoon was filled with animal tracks: the swish marks of a crocodile’s tail, the scrape marks of a hippo’s chin bristles in the sand elephant footprints large and small, lion, leopard and hyena tracks, the indentations of Crawshay’s zebra footprints in the damp river sand and signs of a trifecta of elusive nocturnal creatures – honey badger, porcupine and aardvark.

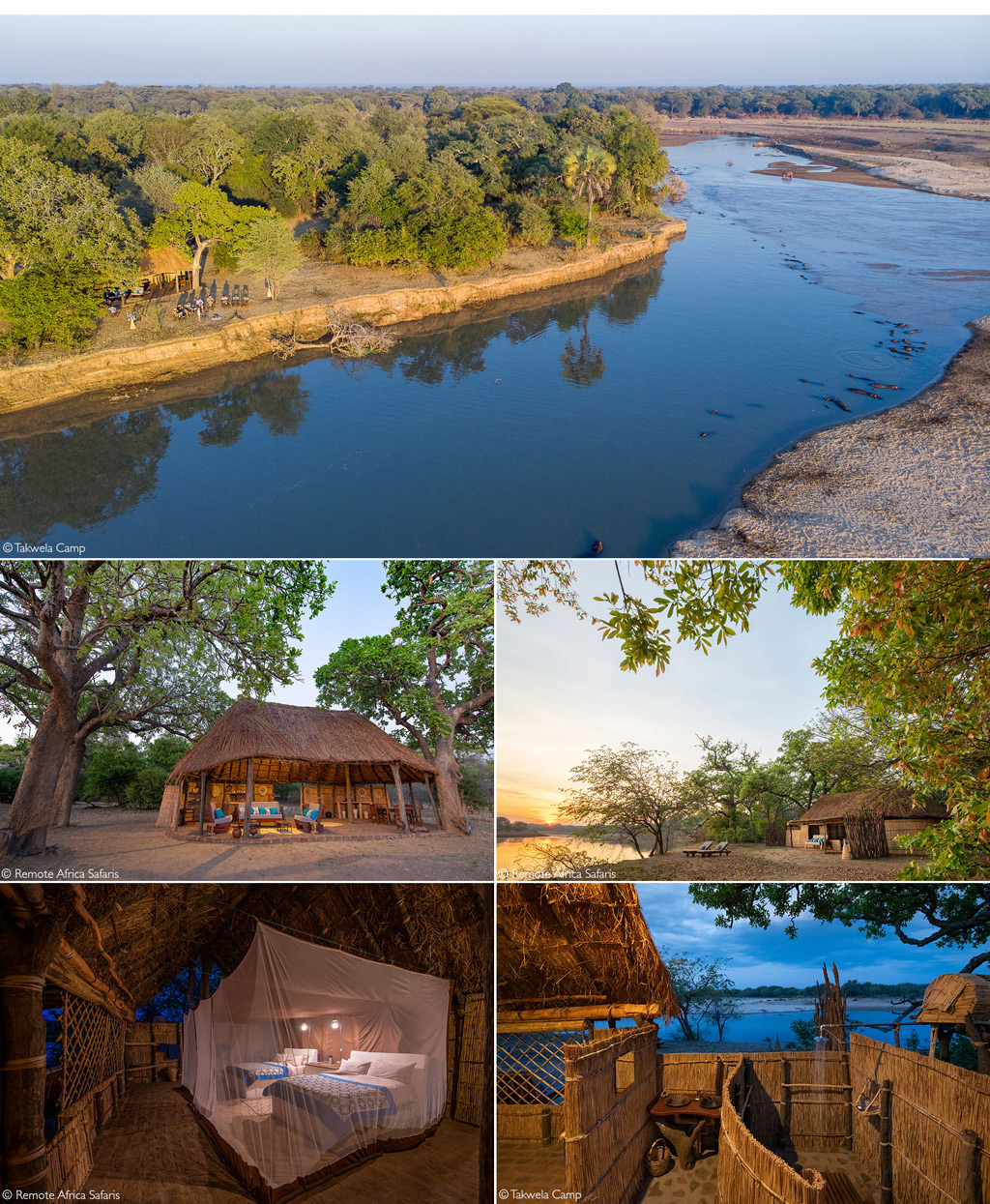

A three-hour walk (or one hour’s drive) downstream from Mwaleshi, in a beautiful part of this mostly unexplored park, is the newly opened Takwela Camp. In the Game Management Area opposite the National Park, at the confluence of the Mwaleshi and Luangwa rivers, the camp offers both walking safaris and game drives. Nestled among groves of African ebony, mahogany, winter thorns and sausage trees, with the occasional ilala palm, the camp is perched three metres above the river. Our room was the perfect vantage point to watch an African fish eagle hunting. He plummeted down to grasp a fish in his talons, resting briefly on the bank before flying off to feast in private. White-fronted and little bee-eaters continued swooping out over the water once he’d gone.

A necklace of fifty or more hippos stretched across the river, resting their chins on a sandbank in the shallow water, grunting and squabbling and sounding like a flotilla of motorboats revving their engines. These creatures fascinated us, and we would spend many hours watching their territorial quarrels and wide-mouthed displays as they jockeyed for prime positions in the water.

Early the next morning we crossed the river in canoes and set off on foot into the park. Handsome kudu and waterbuck gazed passively at us. We followed the tracks of leopard, hyena, genet, aardvark and paused to examine a somewhat pungent civet toilet (civetry). We saw traces of its varied omnivorous diet: digested and excreted rodents, lizards and frogs as well as insects, fruit and berries. A civet is one of the few carnivores capable of eating toxic invertebrates like millipedes, and we saw the remains of the distinctive rings of ‘shell’ left from a digested millipede called a shongololo, (which can grow up to 38cm in length). Finding ourselves with elephants on all sides, never close enough to pose a real danger but close enough to get our adrenalin going, we made a tactical retreat.

Final sundowners in the park were spent on the riverbank, overlooking the same large congregation of hippos, who continued to agitate and disagree over territory. The following day, as we crossed the river to head back to civilisation, we found a pair of shy lions resting on the cool sand in the shade of a mahogany tree. As we were driving out of the park, we rounded the corner to come face to face with a hundred-strong herd of buffaloes – the perfect farewell to our safari.

Want to go on safari to North Luangwa? To find lodges, search for our ready-made packages or get in touch with our travel team to arrange your safari, scroll down to after this story.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()