South Africans have a peculiar affinity for large, iconic trees. The country’s Limpopo province is home to Africa’s tallest tree and the second thickest tree in the world. South Africa even boasts its own Champion Trees Projects since 1998, run by the Department of Water Affairs and Forestry. Landowners and nature enthusiasts throughout the country are exceptionally proud – and rightly so – of the large trees on their properties and in the nature parks they visit, as they make for iconic landmarks and provide shelter to all kinds of species that call the savannah home. Are you wondering how to best protect trees from elephant damage? Which methods work and when? New research, originally published by Elephants Alive, may have the answers.

The threats faced by trees: elephants and other agents

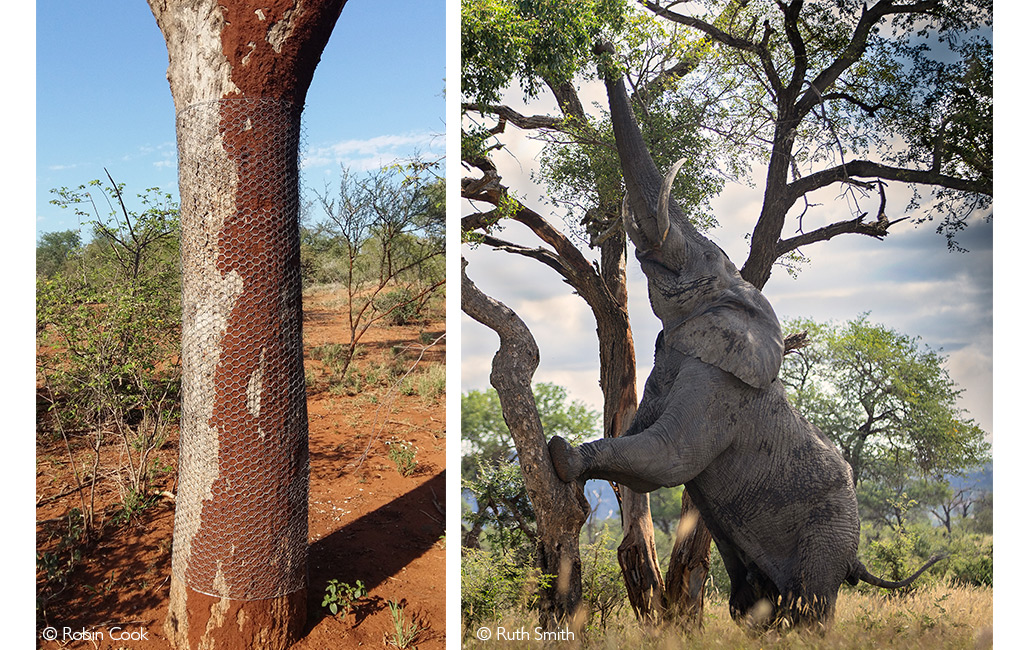

Where nature reserves house elephants, Africa’s largest land mammal is often singled out as the leading cause of destruction of the large trees with which they share the landscape. Elephants break trees to get easier access to the leaves, roots and nutrients. They also remove the bark to access the nutritious cambium layer underneath. As bark often strips off circularly around the trunk, this may lead to ring barking, causing the tree to die off as the cambium layer is responsible for transporting nutrients upwards from the soil. Yet, elephant feeding on trees has been found to benefit other species: dispersing seeds in fertile dung and improving plant diversity by opening up grassland areas, to name a few. However, elephants are selective about the tree species and heights they forage on, and their presence can eliminate certain tree species or height classes from an area over time. This can have cascading effects on other species that depend on these trees, like raptors or vultures nesting in tall trees.

Besides elephants, tree survival in African savannahs can also be affected by other ecological factors, like fire frequency and intensity, termite infestation, and drought stress. High fire frequencies can negatively affect woody biomass and the regeneration of large tree saplings. Drought stress can cause hydraulic failure and vulnerability to biotic attacks, leading to large tree declines even without the presence of elephants. Smaller herbivores, like impala, have been found to decimate great numbers of tree seedlings, thus negatively affecting tree regeneration.

A divisive debate ensues, where concerns about elephants as an endangered species and their role in preserving biodiversity are juxtaposed with the wish and need to preserve large trees as Africa’s natural landmarks. The complex interactions between elephants, other ecological factors, and tree survival in African savannahs have been causing headaches for conservationists and reserve management for decades. Different strategies have been implemented to limit or redistribute elephant impact to protect large trees. For instance, as elephant foraging is primarily centred around water sources, reducing the number of water points may limit the overall effect of localised destruction and population growth.

Protecting large trees: what & how?

Trees may also be directly protected using “wire-netting” to prevent elephants from stripping the bark, which can facilitate tree mortality from various other causes. Wire-netting has previously been found to improve large-tree survival significantly. Highly cost-effective due to the affordability of materials and ease of application, wire netting can be applied en-masse to protect large amounts of trees at little cost. However, little is known regarding the lifespan of wire netting if not maintained and how effective it is as a long-term tree-protection solution.

Offering an answer to this uncertainty, a newly released study by Elephants Alive shows how wire-netting and various environmental factors, combined with the impact of elephants, influence the survival of large trees. The research offers a better understanding of the conservation challenges that reserve management faces while protecting large trees.

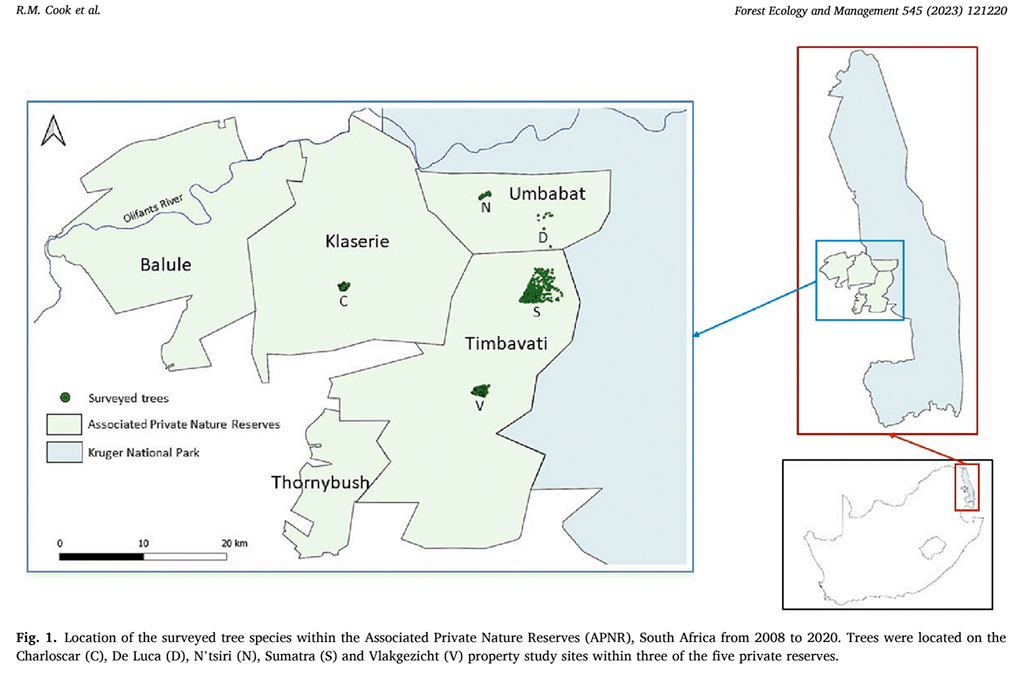

The study was conducted over 12 years in the Associated Private Nature Reserves (APNR) in South Africa. The APNR shares an unfenced boundary west of the Kruger National Park. The Elephants Alive research team, led by Dr. Michelle Henley and Robin Cook, conducted field assessments of 2,758 trees in 2008, 2012, 2017, and 2020. The tree species under investigation were false marula, knobthorn, and marula trees. Approximately half (or 1,395 trees) were wire-netted at the beginning of the study period.

The main goals of the study were to:

- Investigate how many of each type of tree survived over the 12 years in the APNR.

- Examine whether using wire netting to protect the trees affected their survival during the same 12-year period.

- Understand how various environmental factors (drought, fire), combined with the impact of elephants, influenced the survival of these trees during three different surveys conducted within the 12-year timeframe.

During their field assessments, the researchers recorded the diameter of the tree trunk, fire damage, presence of termites, ants and bracket fungus, the level of elephant impact on each tree, whether the tree had wire netting, the condition of the wire netting, and its survival status. For each year, the researchers also collected data on the mean annual rainfall closest to the trees’ location, elephant-bull and breeding-herd densities, and the distance to the nearest surface waterhole.

Wire-netting to the rescue: a simple solution to a complex issue?

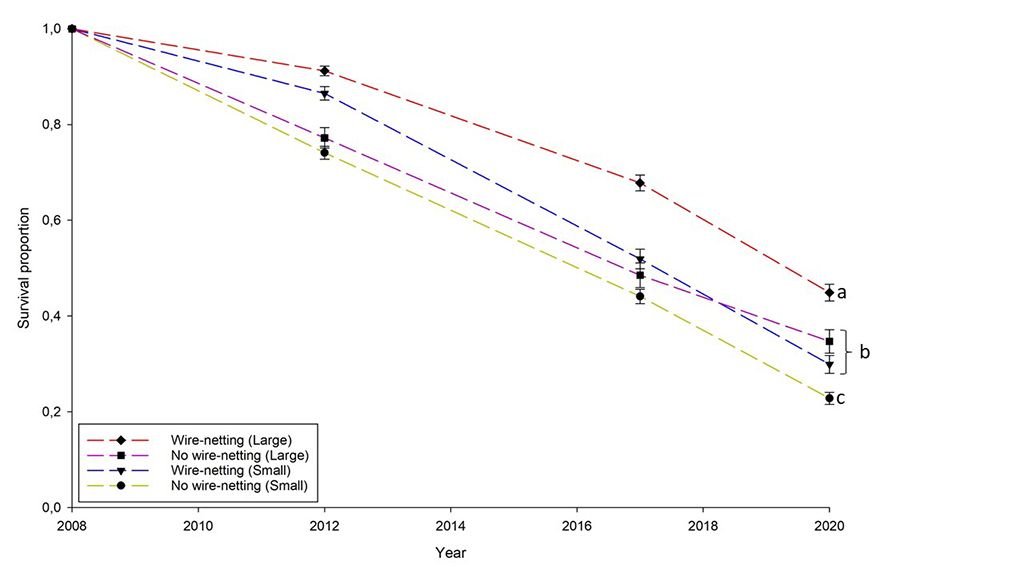

In total, 33% of trees survived the 12-year study period. The distance to water sources did not significantly affect tree mortality, as the multitude of artificial waterholes in the APNR provides ready access to water. This finding emphasises the importance of other methods to limit the detrimental effects of elephant impact on large trees in areas where limiting water sources isn’t an option.

The study showed that using wire netting significantly improved the survival of large trees. Wire netting prevents elephants from bark-stripping, but the trees remain vulnerable to heavier forms of elephant impact like stem snapping and uprooting. Wire-netting is thus most successful for trees with a more than 40cm diameter. The method of wire-netting is a second important aspect of the success rate. Nevertheless, the effectiveness of wire-netting decreased after four years if the netting lost its structural integrity. Over one-fifth of the wire-netted trees in the study had damaged or fallen-off chicken mesh, making the wire-netting ineffective against bark-stripping. This highlights that wire netting can lose its effectiveness if not properly maintained. Conservation managers should consider replacing the chicken mesh after about four years to ensure continued tree protection.

The researchers also discovered tree survival was lowest during drought, particularly for false marula and knobthorn. This suggests that drought can negatively affect the survival of these tree species. Elephants, mainly, increase their impact on trees during drier months when grass quality decreases. This impact may be further amplified for trees with shallow rooting systems (like false marula and knobthorn), making them vulnerable to water stress and competition for soil water compared to trees with deeper roots. An increased percentage of dead marula trees during the final survey period (2018-2020) may be attributed to a fire that affected the area where many of these trees were located. Adult marula trees are particularly susceptible to intense fires, especially after experiencing elephant impact.

Elephants Alive’s research provides evidence of how the complexity of environmental factors has affected the mortality trends of three large tree species within the APNR savannah system over 12 years. The results show that wire-netting can be used as a mitigation method to significantly increase tree survival by reducing elephant impact on these trees. However, conservation managers must replace wire netting every four years to maintain efficiency. The results have also shown that tree survival was positively affected by an increase in mean annual rainfall (for false marula and knobthorn) and negatively affected by fire events (marula trees). These results provide important insights into how various environmental factors have influenced large tree survival where trees co-occur with elephants.

Reference

Cook, R. M., Witkowski, E. T. F. and Henley, M. D. (2023) “Survival Trends (2008-2020) of Three Tree Species in Response to Elephant Impact, Environmental Variation, and Stem Wire-Netting Protection in an African Savannah,” Forest Ecology and Management, 545

Article originally published by Elephants Alive (read Battle of the Titans: Africa’s largest land mammal vs Africa’s largest trees here)

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()