Note from our CEO Simon Espley: ‘This is an emotional topic for most of us. The author of this opinion editorial on Namibia’s elephant auction succinctly differentiates between the science and the ethical issues at play and between fact and speculation. This is a tough read for those of us who believe that there can be no justification for capturing wild elephants and subjecting them to incredible hardships and early death in zoos and other forms of prison. The lucky ones will be moved to large protected areas in Africa, but many will disappear through CITES loopholes into the fog of the wildlife trading industry. That said, it is important to read the facts so that our opinions are informed, and to recognise that solutions have to be found in instances where elephants and humans clash for space and water.’

By Gail Thomson, originally published by Conservation Namibia

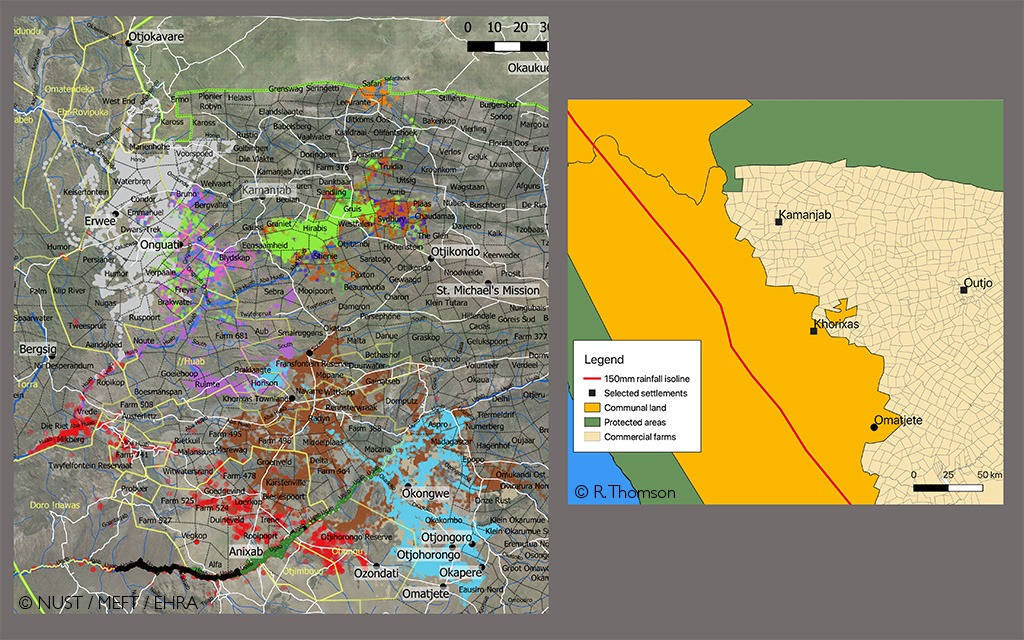

Namibia’s decision to auction 170 elephants from human-elephant conflict hotspots has to date resulted in the capture and translocation of 37 wild elephants from the Kamanjab and Omatjete areas. Both captures for the elephant auction involved family groups of elephants, with one group translocated to a private reserve in Namibia run by N/a’an ku sê and the other exported to two safari parks in the United Arab Emirates (UAE). Following the conclusion of these transactions, more details are now available that allow for an evaluation of the decision to auction elephants and its consequences.

The reasons for this tender are covered in detail in a previous article on this topic. Elephant numbers are increasing and their range is expanding in Namibia, which is both a cause for celebration and concern. The key concern is related to human-elephant conflict, especially in areas where elephants have not occurred for decades. The dominant land use in these areas is livestock farming, where fencing and water infrastructure (pipes, reservoirs, drinking troughs) are not built to withstand elephants.

The elephant removal plan was thus a short-term action to alleviate some of the conflict by removing elephant herds from high-conflict areas, while simultaneously providing income to the Game Products Trust Fund (GPTF). This Fund does not contribute to MEFT’s overall budget, but is ring-fenced for conservation projects and the Human-Wildlife Conflict Self-Reliance Scheme. Long-term plans that MEFT wants to implement to reduce human-elephant conflict would thus be funded through the GPTF. Offers to pay the GPTF without removing any elephants from the target areas were not aligned with MEFT’s primary objective to reduce elephant numbers and did not include specific amounts of money or detailed plans of action. Such vague promises were therefore not considered valid bids.

Thus far, N$ 4.4 million has been paid to the GPTF by two successful bidders. One of these bidders, the N/a’an ku sê Foundation, translocated 15 elephants from the Omatjete area to their newly established private reserve covering 33,000 hectares. The other successful bidder is game farmer Gerrie Odendaal, who bought the elephant herds and resold them to two safari parks in the UAE. Since the latter bid involves exporting elephants into captive conditions outside the natural elephant range, it is the more controversial of the two. (Note that another 20 elephants have been sold on auction but are yet to be captured, and their destination yet to be revealed.)

The main issues involved with capturing wild elephants for the purposes of captivity relate to elephant conservation and welfare. Exporting elephants internationally must further satisfy conditions set by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). Here, I provide relevant information on each of these issues as they relate to the current elephant auction.

Elephant Conservation

There are two aspects of MEFT’s elephant tender that need to be considered to evaluate this decision in terms of elephant conservation. The first is whether there was any conservation value to this decision in Namibia, and the second is whether there is any conservation value at the elephants’ ultimate destinations.

The contribution to GPTF and the short-term alleviation of some human-elephant conflict in the two target areas has some conservation value. This is especially so if the N$ 4.4 million is earmarked not just for conservation projects generally but for implementing longer-term research and conservation projects that aim to reduce conflict and assist local farmers. Alleviating the current conflict by removing some elephants (other herds remain in the area) further shows these farmers that MEFT is willing to take concrete action to reduce conflict in the long term. Evidence of collaborative projects between MEFT, the Namibian University of Science and Technology’s Biodiversity Research Centre and Elephant Human Relations Aid strongly suggest that the elephant removals will be followed up with future assistance.

The case for elephants being exported to safari parks in the UAE having conservation value at their destination is much weaker. The Namibian Chamber of Environment (NCE) strongly agrees with the IUCN African Elephant Specialist Group on this matter: keeping elephants in captivity provides no direct benefit to elephant conservation in the wild. As Dr Chris Brown, CEO of NCE states, “keeping elephants in zoos is a Victorian-era practice that has no place in modern conservation, which focuses on maintaining wild animal populations and their associated ecosystems”.

This is part of a larger debate, however, as zoos and safari parks worldwide claim that they have a role to play in educating the public and creating awareness of the need to conserve animals in Africa. Some zoos provide conservation grants, while others claim to contribute to species conservation through research and captive breeding programmes. One of the safari parks receiving these Namibian elephants is a member of the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA) and the other states that EAZA will be a partner in their future breeding programmes. Both parks have refused to be publicly named as destinations for these elephants.

Regardless of the claims made by zoos and safari parks of their contribution to conservation, it would have been vastly preferable if these elephants were sent to other African range states with depleted elephant populations. As MEFT discovered from the responses to their tender notice, however, there are vanishingly few areas in Africa that are ready to receive elephants at this time. MEFT is certainly willing to engage with other African countries to assist with restocking depleted elephant populations, but one would first have to address the causes of that depletion (e.g. poaching) before undertaking a reintroduction programme.

In early 2020, African Parks signed a management agreement with Iona National Park, which is part of a Transfrontier Conservation Area (TFCA) that includes Namibia’s Skeleton Coast National Park. Elephants from north-western Namibia would therefore be well-suited to conditions in south-western Angola. It will likely take a few years of improving the infrastructure and staff capacity to address poaching in Iona before they are ready to accept elephants. African Parks did not approach MEFT regarding these elephants, so it is reasonable to conclude that they are not ready to receive elephants yet. MEFT is more than willing to support an elephant translocation to Angola provided they receive a formal request from that government.

Moving elephants within Namibia to areas that are suitably fenced is another option, which was provided by N/a’an ku sê’s new private reserve. Like other Southern African nations with growing elephant populations, however, there are very few areas in Namibia that can host more elephants. Translocating the elephants back into Etosha National Park, for example, would have a low likelihood of success because Etosha’s population is close to its capacity. This is why these elephant groups broke out of Etosha in the first place – to seek water and grazing elsewhere. Further, the Etosha fence line is in no fit state to keep elephants inside the park. Even some private farms in Namibia that have elephants struggle to maintain their fences against elephant damage, thus becoming a source of human-elephant conflict rather than a solution.

With clearly limited options for translocating wild elephants to other areas within natural elephant range that could make a significant contribution to conservation, what other options remain for MEFT? The only other practical option for reducing elephant numbers in the short-term is culling. Unlike the tender option, this would provide no income to GPTF. Since CITES prevents international ivory trade, the only value that could be captured from culling is the meat that could be locally distributed or sold. As Botswana discovered, this option is even less popular among the general public than a live elephant auction.

Elephant Welfare

Some of the greatest protests against exporting elephants to captivity are related to animal welfare. Certainly, if the destination of these elephants were small concrete enclosures in disreputable zoos, this move would be rightly condemned on animal welfare grounds alone. The practice of separating young animals from their mothers and training them using cruel or questionable methods to “break” them is abhorrent. The conditions of the Namibian tender (that family groups had to be moved together) were such that unscrupulous buyers such as these would not be interested, and several other conditions set out in the tender document addressed elephant welfare during the translocation process.

Gerrie Odendaal, the game farmer who organised and paid for the translocation, quarantine and export of the 22 elephants destined for the UAE was also concerned for the welfare of these animals. He remained in constant contact with an independent veterinarian and the MEFT wildlife veterinarian during the time that the elephants were in his care. He says that when they arrived at his 28-hectare quarantine facility, the elephants were aggressive and afraid of people, probably because they were continually harassed on the farms around Kamanjab. Odendaal continues, “after a few weeks in my care, they calmed down considerably and even females with young calves were comfortable in the presence of people.” Odendaal commented, “I even fed the older bull with apples straight from my hand, although I respected their space and never approached them on the ground.”

Photos of these elephants reveal neat puncture holes in the ears of some of the older females, which have most likely been caused by small-calibre bullets intended to chase the elephants away from farms where they were unwelcome. Sadly, one of the younger elephants seems to be an orphan. Odendaal speculates: “It is old enough to feed itself, but does not associate closely with any of the adult females. It seems that its mother was killed sometime before we captured the herd.”

The 28-hectare camp is based on the final destination facility at one of the safari parks (the elephant enclosure at the other one is 24 hectares). Prior to the elephants’ arrival, Odendaal’s quarantine area contained large camel thorn trees and plenty of smaller bushes, but the elephants have destroyed these trees in the last few months (the quarantine period had to be extended due to COVID-related travel restrictions). Artificial shade near the feeding area has therefore been provided to replace the shade trees. Odendaal provided bales of lucerne, branches harvested from bushes on the rest of his farm, and hundreds of apples to sustain the elephants’ healthy appetites. The herd was provided with fresh piped water and a muddy pool to cool themselves off.

In consultation with a veterinarian who has many years of experience with elephants, the 22 elephants that were captured in Kamanjab were split into two female herds, with one unrelated bull each, that were delivered to the two safari parks at the same time. While in quarantine, all of these elephants were kept together and the two sub-groups were identified by closely observing how the herd split up when moving around the camp. The elephants that were born in the quarantine facility (having been conceived in the wild prior to capture) were added to the Namibian CITES export permit and were provided with extra care during transit. On the Namibian side of this translocation, every effort was taken to ensure the welfare of these elephants, and the destinations in the UAE seem to be capable of maintaining a high welfare standard.

Concerns nonetheless remain about the destination of the next generation of elephants, if these herds breed successfully in the UAE. Dr Brown comments: “Their future is now out of our hands. Will they land up in Victorian-style, cramped zoos, or in even worse caged conditions in China? What prevents these safari parks from selling elephants on to less reputable places? It is imperative that zoo associations (EAZA and others) ensure that captive elephant populations are carefully monitored to prevent welfare abuses of this nature.”

CITES Permits

Import and export permits are not provided by CITES itself, but each country must have its own national authority that provides such permits, following rules and guidelines set by CITES. The national authorities report to CITES regularly on their numbers of imports and exports, and provide information to the CITES Secretariat on specific decisions when required.

CITES categorises plants and animals that are (or could be) threatened by international trade into Appendix I, II and III (Appendix III is not of concern here). Species in Appendix I are considered to be highly threatened by international trade. CITES therefore restricts all trade in these species, except under specific conditions. Appendix II species are considered to be not currently threatened by international trade, but could become so if this trade is not closely controlled. African elephants are listed as Appendix I in all range states except Namibia, Botswana, South Africa and Zimbabwe, where they are listed under Appendix II.

Previous exports of elephants from Zimbabwe to non-African states (including China and the UAE) were completed under Appendix II guidelines, which state that the animals can only go to appropriate and acceptable destinations. At the most recent CITES Conference of the Parties (CoP18) in 2019, the definition of what is appropriate and acceptable was amended to destinations located within the natural range of African elephants and that contribute to in situ (i.e. in the wild) conservation programmes.

A recent statement by CITES on the Namibian elephant export explains the conditions that national authorities must adhere to when issuing export and import permits for Appendix I and II species. From this statement, it is clear that if Appendix II conditions are not met, the animals must be treated as Appendix I species. Given the recent restrictions on exporting Appendix II species outside of elephant range, these Namibian elephants are being exported and imported under Appendix I conditions.

Under these conditions, the Namibian national authority (MEFT) must be satisfied that this particular deal is:

a) not detrimental to the survival of the species;

b) not illegal under national laws;

c) the translocation methods must minimise the risk of injury, damage to health or cruel treatment; and

d) that an import permit has been granted by the destination country.

The Namibian government has met all of these conditions and is therefore operating within CITES regulations.

As the importing country, the UAE national authority must be satisfied that:

a) the transaction is not detrimental to the survival of the species;

b) the facility where the elephants will be kept is suitably equipped to house and care for them; and

c) the elephants are not to be used for primarily commercial purposes.

The last clause does not refer to money being paid to the exporter for the animals, but for how the buyer in the importing country will use those animals. Since the UAE has granted an import permit that covers both safari parks, it seems that their national authority is satisfied that they meet all three of these conditions (the third condition is described in more detail here).

On final evaluation

The definitive evaluation of MEFT’s decision to auction 170 elephants is thus not straightforward. From a CITES point of view, it is legal. In judging whether or not it was a good decision, one must take into account both conservation and welfare concerns.

For conservation purposes, at the very least, these decisions must not compromise the survival of the elephant population. Removing 170 elephants from farmlands outside protected areas will not have a detrimental effect on the survival of the Namibian elephant population, thereby meeting this minimum condition. The most vulnerable sub-population in Namibia occurs in arid areas on the unfenced communal conservancies and protected areas in the far west: these are commonly known as the desert-adapted elephants. The elephants that were removed are not part of the desert-adapted population, but occur directly south of Etosha.

MEFT and its partners are implementing a longer-term plan to try and mitigate the conflict between farmers and the remaining elephants. It is reasonable to say that a net gain for conservation was achieved for Namibia by selling rather than culling these herds. Nevertheless, keeping elephants in captivity has no direct conservation value, as reintroductions from captivity into the wild are far more costly and risky for the elephants than wild-wild translocations.

On the welfare side, our actions must limit animal suffering as much as possible. In this case, not removing elephants from farmlands also has negative welfare implications, as they may be harassed and even killed by frustrated farmers. We do not know what the elephants would choose if given the option between a safe, boring life in captivity, a dangerous life alongside hostile humans, or a quick death at the hands of a professional culling team. Of the options available for captivity, large safari park enclosures that allow whole family herds to stay together in semi-natural conditions are preferable to individual elephants living in cramped zoo conditions.

In an ideal world, none of this would be necessary. Humans and elephants would have no problems living side-by-side, the elephant range could keep expanding across southern Africa with no difficulties, and poaching would no longer be a problem. No elephants would be kept in captivity worldwide, and anyone wishing to see an African elephant would visit protected areas on the continent and thus boost tourism revenues. Unfortunately, we do not live in an ideal world. In reality, decision-makers have to strike a balance between competing human and elephant needs, while taking elephant conservation and wildlife safaris into account.

Resources

Dive into the key questions for human-elephant conflict research.

Read more on the story behind the Namibian elephant auction.

Learn about the great balancing act between elephants and communities.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()