Mukalya Private Game Reserve in Zambia

The sun slips towards the horizon, turning the sky from blue to shades of pale pink and orange. We’re staying at Mukalya Private Game Reserve (upstream from Lower Zambezi National Park and downstream of Victoria Falls) and have just spent the afternoon fishing on the Zambezi River in Zambia. As we drift downstream, we catch sight of an elephant, a lone young bull, who uses his prehensile trunk to grasp clumps of grass and leaves. He slowly ambles along the bank, almost keeping pace with our drifting boat for a couple of kilometres, before he climbs the steep bank and disappears.

My husband resumes fishing, and I continue to watch the bank where groups of women gather to wash the family laundry and children splash in the shallows. Men relax, chat, and doubtless discuss the merits of various fishing sites and methods. We drift past islands, big and small.

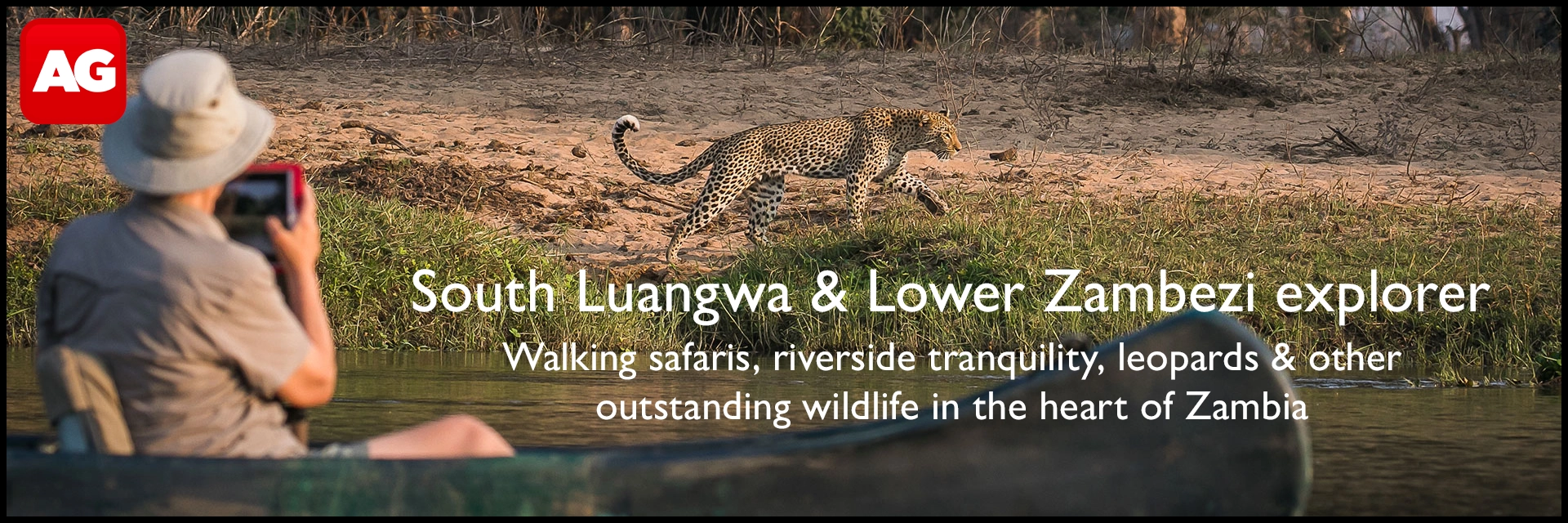

The massive corkscrew horns of a kudu bull loom above the boat as we glide on, while impala gaze passively down from the riverbank and pied kingfishers dive for fish. Then, a movement on the bank catches our eyes. A magnificent male leopard, indifferent to us, saunters along the soft sand. We watch until he disappears.

My husband begs for “one more cast”, and his afternoon suddenly improves as he hooks a tiger fish. The river predator puts up a brave fight but, after a brief tousle, is landed, weighed, measured, photographed and returned to the water. A leopard and a ‘tiger’ in one afternoon – impressive.

Mukalya Private Game Reserve

We are staying at Mukalya Private Game Reserve on the banks of the Zambezi. Seventy years ago, this was an area of incredible biodiversity and wildlife. It was also where most of Zambia’s rhino lived. However, poaching, habitat loss caused by deforestation (both for farming and charcoal production) denuded the area of wildlife. Just over a decade ago, barely an animal was to be seen. Then in 2006, on a canoe trip down the river, a family fell in love with the area and decided to restore it. They developed a vision for reintroducing wildlife, protecting the forests and restoring the space to its former glory.

Once they had securely fenced the reserve, they began reintroducing wildlife and educating the local villagers about the value of wildlife conservation. To date, the family has reintroduced 14 mammal species (including sable, eland, tsessebe, giraffe and zebra). This was not a process without its challenges. Some animals died during transportation; others failed to adjust to their new environment. A severe drought necessitated additional feed while elephants and hippos regularly broke fences, causing costly repairs. A pride of lions swam across the river from the Zimbabwean Hurungwe Game Management Area and consumed many newly introduced residents.

Conflict

Initially, there were also challenges with the members of the local community. Poaching, conflicts over boundaries, and widespread tree felling were some. But the family’s hard work has paid off. Local people are now benefiting through much-needed employment and social projects that include community schools, clinics, solar lighting, agricultural inputs for local farmers, wells and the provision of water pumps. In addition, the family has worked with the Zambian Wildlife Authority to reduce poaching and have not lost a single animal to illegal hunting in the last six years. Indeed, when an animal escapes from the Mukalya now, the local villagers inform the family and play an active role in herding the escapee home.

Turning to tourism

The re-stocking project was costly, as were the ongoing costs of staffing and maintaining the reserve. With this in mind, the family recently decided to open a tourism operation to help the reserve support itself.

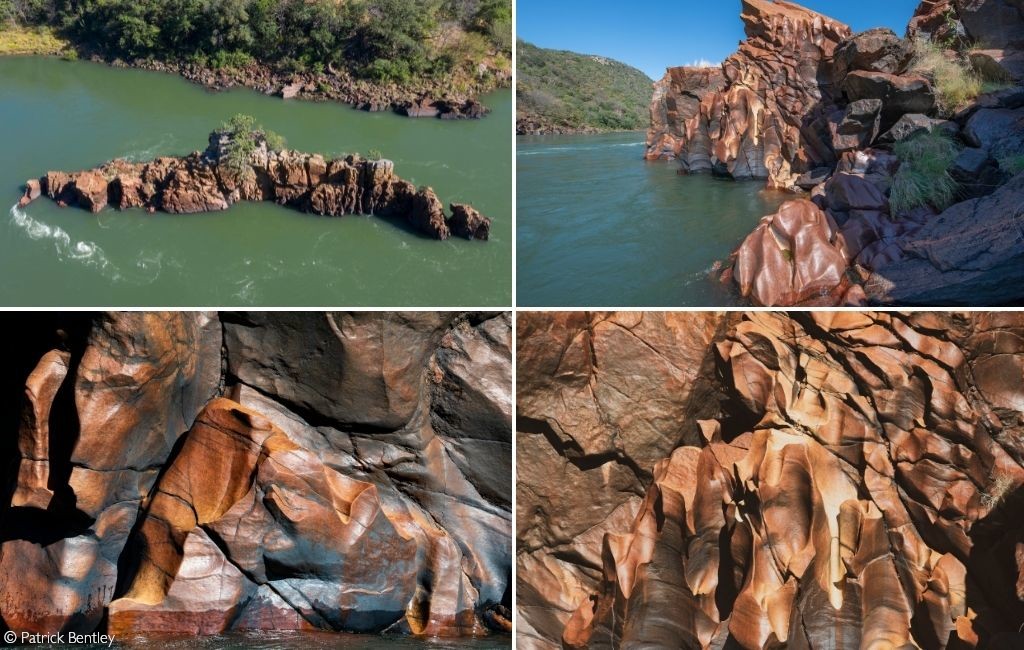

The previous afternoon we had headed upstream and into the Kariba Gorge. The river here has carved its way through the basalt rock, creating dramatic cliffs. As we entered the gorge, the river narrowed. Water swished and swirled around our boat. The precipitous banks are covered in dense vegetation, and we passed the occasional sandy beach and seasonal waterfall cascading into the river. There were scores of fish eagles dotted in the trees above the turbulent waters. In the shadows of the gorge, we saw two rare, rufous-plumaged Pel’s fishing owls.

Heading further upstream, towards the Kariba Dam (the largest dam in the world for storage capacity), we passed ‘Nyami Nyami Rock’. Local legend has it that this rock island is the Zambezi River God, Nyami Nyami, trapped forever in the river below the wall, while his wife remains trapped in the dam above. Traditionally, superstitious fishermen wouldn’t pass this rock and would never fish upstream of it, but time has softened traditions, and we saw a couple of dugout canoes and local men trying their luck as we headed towards the wall.

The closer we got to the wall, the more the water seethed and swirled, rushing over rocks and creating hundreds of tiny whirlpools. Then, suddenly, it loomed out of the water ahead of us. We sat in the boat, engine idling, and looked up at the massive construction, holding back 185 billion cubic metres of water.

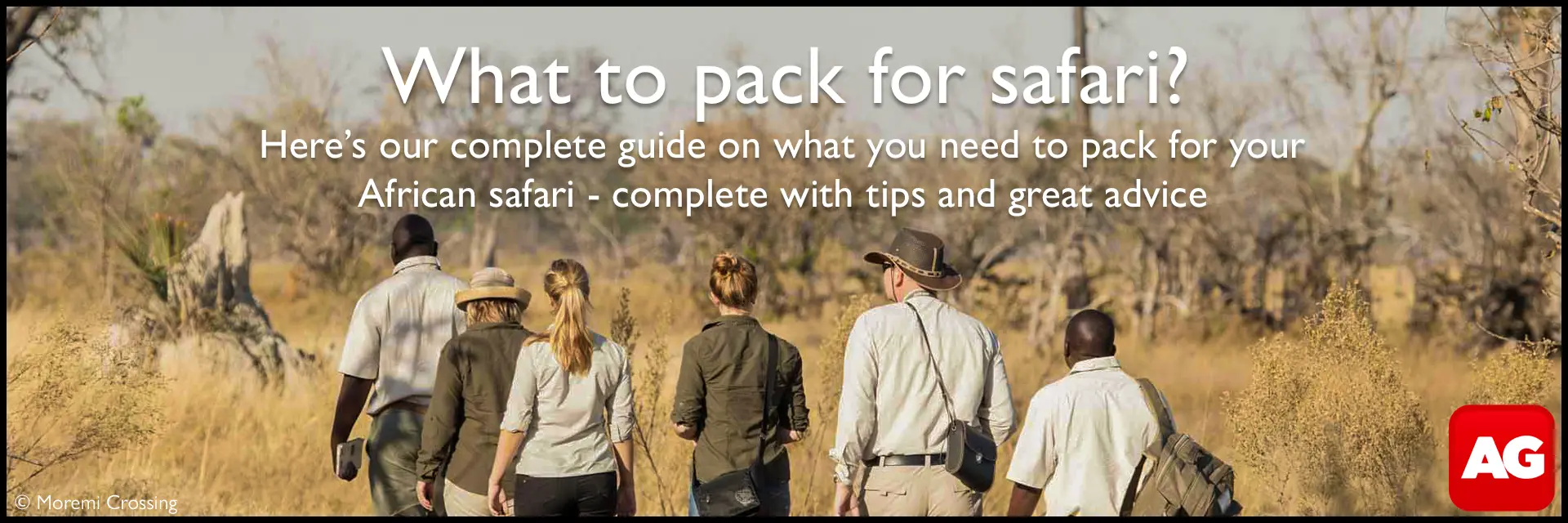

Strolling in the wild

The following morning, we explored the local area on foot – a 12km round trip to some hot springs. We walked through the reserve, surrounded by groves of false chestnut trees (local name Mundoli, scientific name Triplochiton zambesiacus). These vast, wide-canopied trees, with mottled, grey-white bark, large-lobed leaves and clusters of pale yellow flowers, are restricted to the Zambezi Valley.

We spotted kudu, duiker, sable and waterbuck in the dappled shade. An African golden oriole flew overhead, and we stepped over the fat tracks of a python. We had hoped for a sighting of the elusive, migratory African pitta (formerly Angolan pitta), which is in the area from November to February. It was March, and sadly there were no lingering pittas. We did see and hear a variety of other birdlife, however.

Between August and November, thousands of southern carmine bee-eaters paint the sky, bushes and steep, sandy riverbanks dazzling pinks and blues. We stood in the dry bed of one the Zambezi’s tributaries and marvelled at the extensive network of tunnels excavated into the towering banks above.

We were there at the right time to examine some of the smaller critters, including creepy, omnivorous (and occasionally cannibalistic) harvester crickets. We also watched numerous spider-hunting wasps, which paralyse their prey, burying it live with their eggs, to provide the young with ‘fresh’ food.

Hot Springs

Leaving the reserve behind, we walked through local villages, waving at cattle and goat herders, greeting school children and stopping to have a chat with the village headman, before reaching the hot springs. At 90°C, the water was much too hot to touch, and clouds of mist rose above it in the cool morning air. Local women sometimes bring their pumpkins here to cook in the hot water while they tend the fields nearby. Further from the source, in a shaded clearing, the water was cooler, and our guide told us that bathing here, with the natural salts, sulphur and other minerals, has numerous health benefits. We didn’t stop to swim though; our tummies were rumbling.

Brunch was a scrumptious affair, and after our morning exertions, we felt we had earned it. Zebra looked on while we sat and chatted with the family. Uncle Josh regaled us with tales of the past, the giant trees that had grown here, and the wild animals roaming the area before poaching and human encroachment changed everything.

Sitting, coffee in hand and bellies full, we chatted with Michael, the driving force behind the project. He spoke of Mukalya’s future – the expansion of the reserve, the reintroduction of more animals, combating deforestation, plastic waste reduction, recycling projects, sustainable local fishing methods and future community projects. The family hopes to drop fences with neighbouring properties to increase the conservation footprint.

We couldn’t help but be inspired by the passion and commitment that has gone into the development of Mukalya Private Game Reserve. We hope the future will be a bright one and that it won’t be long before we return to check on progress.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()