There is a great deal of mystique surrounding the Bushman/San and their tracking prowess. Fuelled by storytellers from Laurens van der Post to latter-day mythologists, the legends live on, rendered now deeply poignant by the plight of the remaining ancients. People on the brink.

The Ju/’hoansi of Nyae Nyae

The Ju/’hoansi of Nyae Nyae in Namibia are the last standard-bearers of southern Africa’s hunter-gathers. For, uniquely and tragically, only they have the full suite, however precarious: their signal click language, access to wild land, the legal right to hunt by traditional means, and a slender, unbroken knowledge bridge to millennia upon millennia of savanna-attuned living. They hold the flinted keys to surviving and thriving in a pre-agricultural, pre-industrial world.

I went to the remote //xa/oba settlement in north-eastern Namibia because there, as Louis Liebenberg told me, I would find three old-way geniuses: /ui-Kxunta, /ui-G/aqo and ≠oma Daqm. Indigenous Master Trackers. The only three formally recognised as such in Namibia, although there are others out there, scarcely known, talents unseen.

In the scrubby grasslands of Bushmanland they showed me how they could stay on the tracks of gemsbok (oryx) for as long as my water bottle lasted in the scorching heat (a couple of hours). They pointed out in the soft sand two sets of blurred parallel tracks of some four-legged creatures – a bat-eared fox and black-backed jackal, they said.

Now anyone who has walked through mopane thickets in Kruger knows how maze-like they can be. One tousled bush looks very much like every other. A good place to get lost. The same can be said of the terminalia scrub of Nyae Nyae. We set off following roan tracks and came across a mamba, the continent’s deadliest snake, disappearing into the bush. Some hours later, as the trackers threaded their way unerringly back through the uniform bushveld to wherever we had left the vehicle, we passed yet another indistinguishable bush. “That’s the mamba bush”, they said. Okay. No questions.

A rare skill, this tracking art. There are probably only a dozen masters of the intact African lineage left alive. And yet the bearers of this long and riveting history, the //xa/oba community, face constant food insecurity and are burdened by wholly treatable diseases, TB foremost. Little by way of employment. Hunting and gathering has its limits in depleted Nyae Nyae. Poverty is their crushing condition.

Across the Kalahari Basin, this is the 21st century signature of being San.

Displaying extraordinary tracking prowess in the Kruger

About a million and a half tourists visit the Kruger National Park each year. About ten thousand of the more serious devotees go on wilderness walks. Walking through the bush brings all the senses into play, the full symphony, along with a sense of trepidation – you are back where it all began, on the African savanna. Predators, prey, and dust.

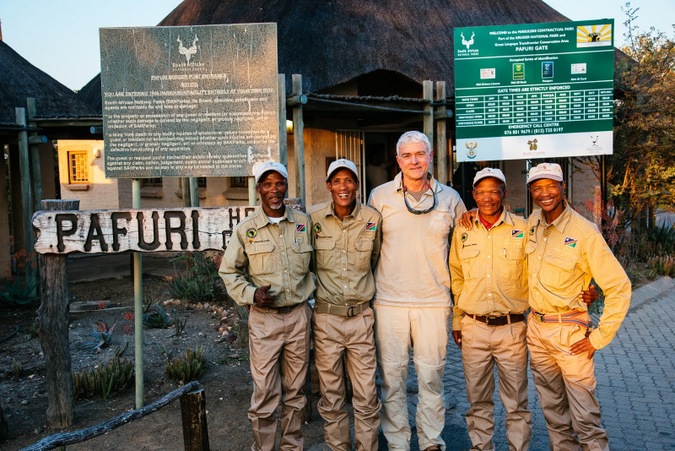

And so, on 28 June 2018, the three Namibian masters plus another tracker, Dam Debe (last seen in the movie, The Gods must be Crazy, as a child) arrived at Kruger’s northern Pafuri Gate. The first day in the Makuleke Concession was for orientation, and sightings of civets, white-tailed mongoose, bushbuck, and nyala were all unknown animals to them, though not for long – once seen they became firmly imprinted in their minds.

They tracked an eland – totem of many a Bushmen clan. They narrated its movements for us: “Here the bull stopped, half-turned and looked back at us. Then it went on. Here it nibbled at the end bits of the mopane. See the moist twigs. See the crumbs on the ground. Now it has trotted off at speed. We won’t be seeing it again.”

The next day we went far off the beaten track to Makuleke’s bushman painting site. The last San walked this precipitous sandstone terrain perhaps three hundred years ago. Our local lead guide went a little astray, as she wound her way over-circuitously through heavily vegetated gullies and ridges to the gallery.

The trackers, even though they were walking behind us, cautioned us of the buffalo in the thicket ahead before we even heard or saw them. No oxpeckers around to give us their rasping warning chirrups.

That figurine on the cave wall which everyone had seen as an eagle was in fact a person wearing a kaross, they told us. That which we thought was a human was an animal, but the forelegs had been washed away by centuries of seepage.

In jest, I asked one of the trackers to take us back to the vehicle – hills and dales away. Nyae Nyae is boundlessly horizontal – plains and pan country, without rocky outcrops. The occasional baobab spears the distant perimeter. Makuleke’s bushman paintings are tucked away in the hills, just before the land plunges down to the Luvuvhu River. Clarens sandstones, basalt ridges, thick vegetation, mosaic topography – an utterly alien 3D world for a 2D Kalaharian.

“Sure”, he said. It had taken us forty-five minutes to labour away through the crumpled landscape to the paintings. It took our tracker twenty minutes to cut his way directly back to the road, just short of the vehicle.

“Could have come out at the vehicle,” he said. “But quicker to hit the road first.”

The Bushmen of old had a pact with lions: We don’t hunt them, they don’t hunt us. It had worked for /ui-G/aqo years ago in Nyae Nyae when, alone on a hunting trip and sleeping up in an acacia thicket, he was surrounded in the middle of the night by a pride. He told us that the lions of the human spirit told the others to leave him alone, and they did.

I was wondering about the currency of that pact as we tracked lions in Kruger’s Nyalaland wilderness.

The trackers then pick up the tracks of a paired lion and lioness.

“They have switched from ambling to hunting,” they say.

“How so?” I ask.

“Because now they are walking apart and see, their paw prints have become slightly smaller. Their muscles are tensing.”

Then the trackers stopped where the lions had frozen a little earlier, and looked ahead to the right. They walked twenty-five paces in that direction.

“Come here,” they beckon us over. “This is where a buffalo bull meandering along suddenly smelt the lions, stopped and stared at them. Then he bolted away – look at the dig mark in those tracks. The lions bounded after him, but not far. They gave up.”

Over six walking trails, four in Makuleke and two in Nyalaland, and the masters never did lose any of the tracks we chose to follow, even when the quarry turned out to be beyond our endurance to find. This was no problem to us at all, as the fascination was in the twisting journey, not an embodied destination.

We had some knowledgeable people on the trail, including accomplished Kruger guides – and their faces said it all. Each tracking episode ended with guest and guide shaking their head in stunned appreciation, then handshakes all round. It was better than an opera and in the best of opera houses.

To comment on this story: Login (or sign up) to our app here - it's a troll-free safe place 🙂.![]()